Introduction

After changes to federal immigration law in 1996, local law enforcement officers began working more with federal immigration officials. New programs were aimed at promoting public safety by removing dangerous criminals from the United States. Two major programs, 287(g) and Secure Communities, involve local police departments working with the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to some degree. The Secure Communities Program was in place between 2008 and 2014 until it was replaced by the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP), which targeted the most dangerous offenders. Secure Communities was reinstated by President Trump in 2017, ending PEP with the purpose of enhancing public safety.1Michael Coon, “Local Immigration Enforcement and Arrests of the Hispanic Population,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 3 (2017): 646–66, https://doi.org/10.14240/jmhs.v5i3.102.

Critics of cooperation between ICE and local police departments argue that broad programs like 287(g) and Secure Communities have been ineffective and even counterproductive for promoting public safety. They argue that such programs deter immigrant communities from cooperating with police out of fear that the police will initiate deportation proceedings. Even authorized immigrants may live with an undocumented family member and so may be unwilling to cooperate with the police.

This Research in Focus examines research describing the costs and benefits of using local and state law enforcement to carry out federal immigration policies. The evidence shows that broad immigration enforcement programs do not successfully reduce crime or improve public safety, mainly because they often fail to target serious offenders. In addition, several studies suggest the programs have real social costs, including decreased educational attainment and less crime reporting. More targeted programs, like PEP, are likely more effective.

These findings suggest that federal policymakers need to keep immigration enforcement programs that use local and state officers focused on serious offenders. Local officials can best promote public safety by introducing more inclusive immigration policies. Relying on community policing, promoting cooperation with law enforcement, and encouraging immigrants to integrate into their communities are more promising than sweeping enforcement efforts.

287(g) and Secure Communities

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act added article 287(g) to the Immigration Nationality Act. Creating what are called 287(g) programs, this legislation enabled ICE to provide local and state law enforcement officers with the legal authority to assume ICE functions.2Coon, “Local Immigration Enforcement,” 647.

When the 287(g) program was introduced, it focused on identifying and removing any suspected illegal immigrant. This meant that the program originally had police determine the immigration status and arrest anyone they came across, regardless of criminal status, and arresting people with immigration violations. Inconsistency among 287(g) programs led ICE to restructure the program in 2009.33. National Immigration Law Center, Fundamental 287(g) Problems, National Immigration Law Center, April 2010, https://www.nilc.org/issues/immigration-enforcement/287g-oig-report-2010-04-29/. Under the current provisions of the 287(g) program, unauthorized immigrants arrested by local and state law enforcement are identified and processed by the justice system. After serving their sentence, offenders are transferred to ICE custody.4Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Delegation of Immigration Authority Section 287 (g), Immigration and Nationality Act (Washington, D.C.: Department of Homeland Security, 2008), https://www.ice.gov/287g.

In 2017, emphasis returned to a related program which was originally implemented between 2008 and 2014, Secure Communities. Secure Communities also relies on local and state law enforcement, but it does not empower local law enforcement officers to make inquiries or arrests based on immigration status. Secure Communities is largely a program for information sharing between local law enforcement, DHS, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).5Emily M. Farris and Mirya R. Holman, “All Politics Is Local? County Sheriffs and Localized Policies of Immigration Enforcement,” Political Research Quarterly 70, no. 1 (March 1, 2017): 142-54 at pp. 144.

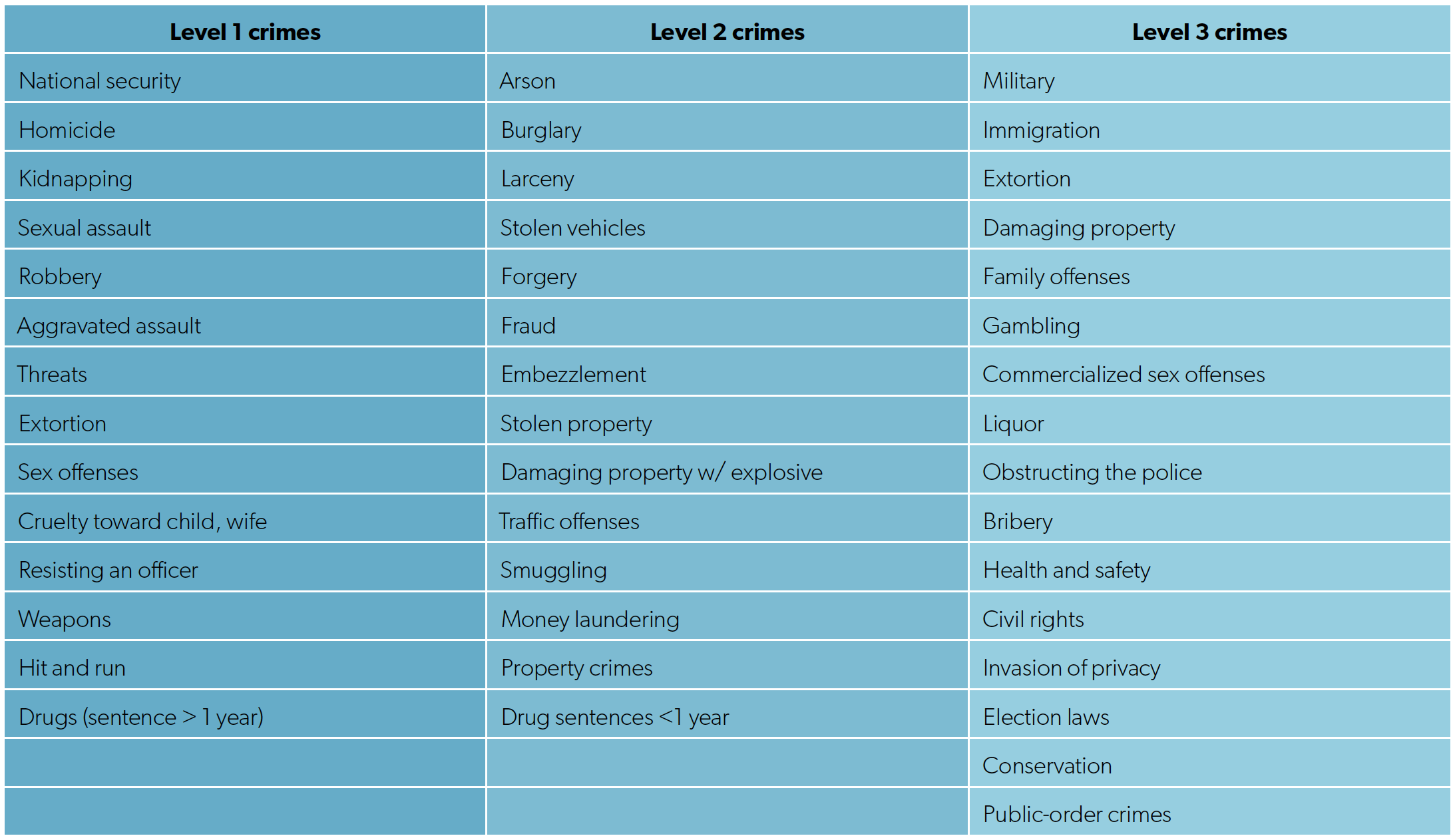

When a person is detained, that person is fingerprinted, per normal procedures, and those prints are shared with the FBI. However, Secure Communities allows the FBI to send these fingerprints to DHS. DHS then uses these fingerprints to identify an arrestee’s immigration status and determines how to proceed. ICE can then issue a detainer which requests that an offender not be released from the custody of local law enforcement until ICE is able to detain the individual. Offenders are prioritized based on the severity of crimes, ranging from high-priority (level 1) offenders (charged with crimes such as homicide and assault) to lower-priority (levels 2 and 3) offenders (charged with minor offenses).

Figure 1: ICE Offense Levels Defined6Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Secure Communities (SC) Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), accessed May 22, 2020, https://www.ice.gov/doclib/foia/secure_communities/securecommunitiesops93009.pdf.

ICE argues that programs such as 287(g) and Secure Communities represent a “common sense” method of immigration enforcement.77. “Secure Communities,” Immigration and Customs Enforcement, accessed May 18, 2020, https://www.ice.gov/secure-communities. Yet the academic literature offers a wide range of criticism challenging the claim that such programs achieve their public-safety goals. Some critics are also concerned about these programs’ potential economic and social harms that are unrelated to crime.

Why These Programs Don’t Work

Enforcement Is Overly Broad and Picks Up Low-Level Offenders A major problem with current immigration-enforcement programs is that they include individuals who are not an imminent threat to their community. Research verifies the overly broad nature of 287(g) programs. One 2009 paper focuses on the impacts of the 287(g) program in Alamance County, North Carolina. The paper concludes that the majority of those apprehended under the program were traffic offenders.8Hannah Gill, Mai Thi Nguyen, Katherine Lewis Parker, and Deborah Weissman, “Legal and Social Perspectives on Local Enforcement of Immigration under the Section 287 (g) Program,” University of North Carolina School of Law Carolina Law Scholarship Repository, 2009, 1-18 at pp. 13.

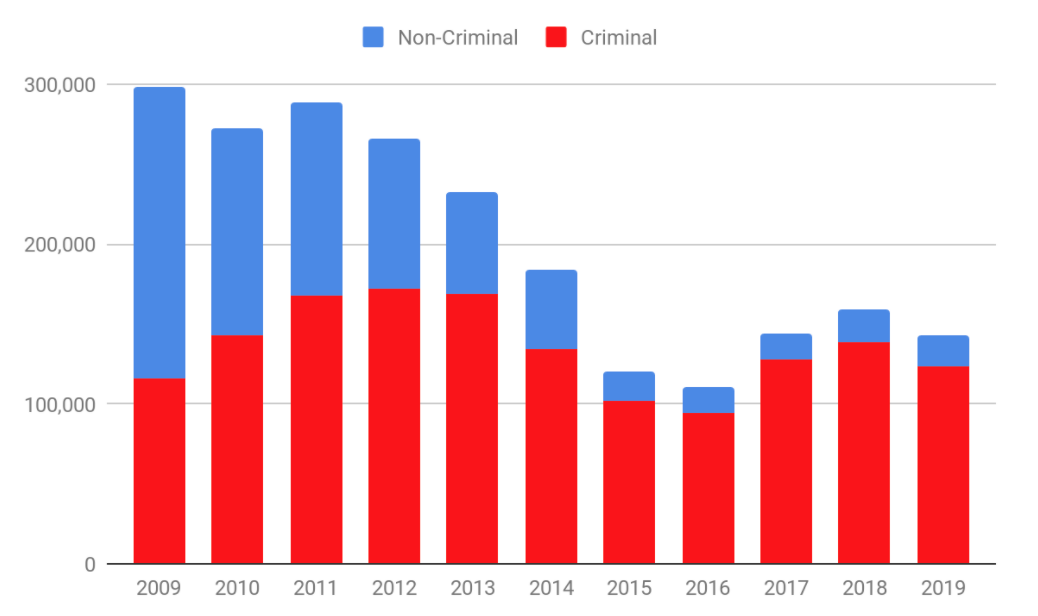

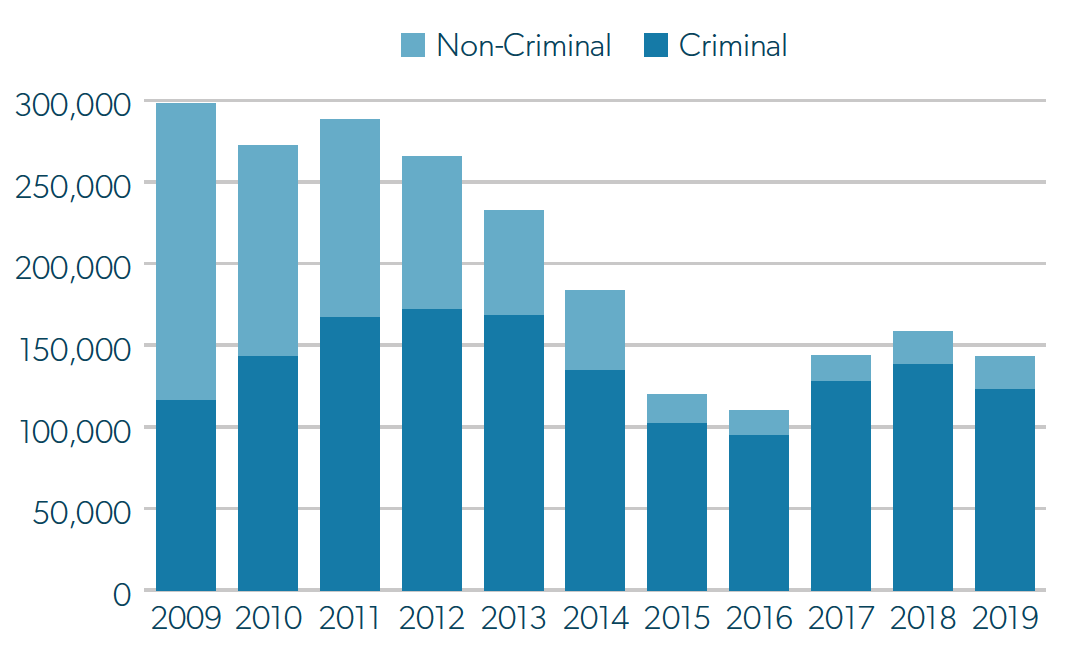

The Secure Communities program leads to similar outcomes. Research shows that a significant number of people apprehended because of 287(g) or Secure Communities programs are minor offenders or noncriminals.9Michele Waslin, The Secure Communities Program: Unanswered Questions and Continuing Concerns, (Washington, D.C.: Immigration Policy Center, 2010), 1-22. Between 2009 and 2019, at least twenty-seven out of every hundred arrestees were noncriminals.10ERO Administrative Arrests by Criminality and Fiscal Year. (2017), distributed by U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement FOIA Library. https://www.ice.gov/foia/library; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Fiscal Year 2019 Enforcement and Removal Operations Report,” Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2019, 1-32 at pp. 13, https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Document/2019/eroReportFY2019.pdf. These noncriminal arrestees are individuals who do not have any criminal convictions or pending criminal charges.11 Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report,” Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2017, 1-18 at pp. 3, https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/iceEndOfYearFY2017.pdf. However, that average obscures changing enforcement priorities over the past decade, which is shown in Figure 2. Between 2009 and 2014, more than half of the enforcement actions targeted noncriminal immigrants. Since 2015, the number of noncriminal arrests has fallen. They now make up about 13 percent of all arrests. This outcome is likely the result of the transition away from Secure Communities in 2014 to the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) which uses the same fingerprinting process to identify offenders but focuses attention on those who pose the greatest risk to society.12Priority Enforcement Program,” www.ice.gov, accessed August 18, 2020, https://www.ice.gov/pep;

Figure 2. Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) Administrative Arrests by Criminality Status, 2009-2019

Note: ICE distinguishes between criminals without known convictions or pending criminal charges and those with known criminal charges. We consider those with pending criminal charges as criminal for years 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 using ICE’s end of year reports. The data for 2009 to 2015 come from DHS’s response to questions for the record from a 2016 Senate Judiciary Committee meeting.13Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Fiscal Year 2019 Enforcement and Removal Operations Report,” Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2019, 1-32 at pp. 13, https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Document/2019/eroReportFY2019.pdf; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report,” Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2017, 1-18 at pp. 3, https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/iceEndOfYearFY2017.pdf; Thomas Homan, “Senate Committee on the Judiciary Questions for the Record: Declining Deportations and Increasing Criminal Alien Releases,” 43, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Homan%20 Responses%20to%20QFRs1.pdf.

The changes in the data show how the PEP’s narrow targeting of dangerous criminals likely made it more effective compared to broad programs such as 287(g) and Secure Communities which were not designed to focus on the most threatening individuals. Existing research supports these claims by showing evidence that it produced benefits for both immigrants and the American population in general. A recent study comparing widespread versus narrow enforcement found that prior to the Department of Homeland Security shifting its efforts towards criminal arrests, a higher propensity of deportees were arrested for minor offenses such as traffic offenses and drug use violations. This compares to outcomes following the narrowing of policy where less immigrants were solely detained for minor offenses, and deportees spent less time in detention. Less time in detention is associated with an estimated $81 million in savings for the U.S. government, funds which could be reallocated to benefit taxpayers through investments in education and job training programs.14Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, Thitima Puttitanun, and Ana P. Martinez-Donate, “Deporting ‘Bad Hombres’? The Profile of Deportees under Widespread Versus Prioritized Enforcement,” International Migration Review 53, no. 2 (April 26, 2018): 531–41, https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318764901. A similar study looking at the effects of the PEP in Dallas also found that the switch to PEP led to a higher number of detainments for dangerous crimes rather than primarily immigration-related crimes.1515. Elisa Jacome, “The Effect of Immigration Enforcement on Crime Reporting: Evidence from the Priority Enforcement Program,” Working Paper, 2019, https://sites.google.com/view/elisajacome/research.

Immigration Enforcement Does Not Reduce Serious Crimes

Prioritized enforcement is important, as apprehending even a small number of serious criminals might reduce crime rates and benefit communities. Additionally, studies show that broader immigration enforcement efforts have not provided evidence of reduced crime rates. When cities participate in programs to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement, the rates of major crimes do not decrease. For example, a study comparing participation in and the extent of 287(g)-programs using annual FBI crime data between 2003 and 2015 in North Carolina shows that implementing the programs did not decrease rates of violent crime or property crime.16Andrew Forrester and Alex Nowrasteh, “Do Immigration Enforcement Programs Reduce Crime? Evidence from the 287(g) Program in North Carolina Authors,” Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, 2020, 1-40 at pp. 7–11, https://www.thecgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/working-paper-2020.004.pdf.

Criminal-justice experts Elina Treyger, Aaron Chalfin, and Charles Loeffler analyzed monthly crime rates in 335 US cities between 2008 and 2011 to examine whether implementing Secure Communities reduced major crimes such as murder, rape, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. Overall, they found that cities with the most immigrants did not see significant reductions in crime rates after implementing the Secure Communities program. Locations with the largest proportions of Hispanic residents also did not see a significant decrease in crime rates.17Elina Treyger, Aaron Chalfin, and Charles Loeffler, “Immigration Enforcement, Policing, and Crime: Evidence from the Secure Communities Program,” Criminology and Public Policy 13, no. 2 (May 19, 2014): 285-322 at pp. 300, 303, 306.

A third study finds similar results at the county level. Using data from 2,985 counties between 2004 and 2012 to compare crime rates following the implementation of the Secure Communities program, the study finds no reduction in the FBI overall-crime index in counties with Secure Communities. Burglary and motor theft fell, but although the reductions were statistically significant they did not represent meaningful improvements to public safety as they accounted for less than 1 percent of these crimes.18Thomas J. Miles and Adam B. Cox, “Does Immigration Enforcement Reduce Crime? Evidence from Secure Communities,” Journal of Law and Economics 57, no. 4 (November 1, 2014): 937-973 at pp. 954, 956, 969. Given the research showing that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than similar natives and that these enforcement programs primarily affect low-level offenders, the finding should not be surprising.19Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny, “Do Immigrants Threaten US Public Safety?” Journal on Migration and Human Security 7, no. 3 (September 2019): 52–61, doi:10.1177/2331502419857083.

Overall the research suggests that programs such as 287(g) and Secure Communities do not substantially reduce crime.

Immigrants Commit Crimes at Similar Rates to US Natives These programs are also ineffective because immigrant populations are not plagued with criminal activity. Various studies show that immigrant populations have crime rates similar to, if not lower than, comparable nonimmigrant populations.2020. Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny, “Do Immigrants Threaten US Public Safety?” Journal on Migration and Human Security 7, no. 3 (September 2019:52- 61, https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502419857083. Sociologists comparing crime statistics on immigrant and nonimmigrant populations found no relationship between legal status and violent crimes, including homicide and rape. They found a weak relationship between undocumented populations and drug-related arrests, however.21 David Green, “The Trump Hypothesis: Testing Immigrant Populations as a Determinant of Violent and Drug-Related Crime in the United States,” Social Science Quarterly 97, no. 3 (May 31, 2016): 506-534 at pp. 509, 512–14, https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12300.

Other literature suggests that immigrants actually reduce crime by revitalizing local areas. A study comparing crime rates in various locations finds that locations with increasing immigrant populations see decreases in crime rates.22Vincent Ferraro, “Immigration and Crime in the New Destinations, 2000– 2007: A Test of the Disorganizing Effect of Migration,” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 32, no. 1 (February 14, 2015): 23-45 at pp. 23, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y.

Overwhelmingly, research on immigration and crime shows that immigrants are not more prone to committing crimes than similar US natives. Policymakers may better improve public safety by shifting the resources devoted to broad enforcement programs toward targeted programs pursuing the most dangerous individuals, regardless of immigration status. In the same way that law enforcement targets only dangerous natives, immigration-related crime programs should target the few immigrants who commit serious crimes.

Immigration Enforcement’s Unintended Consequences

In addition to failing to meet its intended purpose, programs such as 287(g) and Secure Communities have unintended negative consequences. For example, academic research suggests these programs decrease trust in the criminal justice system and appear to reduce educational attainment among immigrant communities.

Immigrants Are Less Likely to Report Crimes

Targeting innocent individuals and minor offenders creates ripple effects that may decrease community safety. Multiple studies underscore how immigration-enforcement programs erode trust in local law enforcement and therefore decrease crime reporting. Immigration scholar Michele Waslin found evidence that the 287(g) program and Secure Communities decrease the ability of local law enforcement agencies to develop a trusting relationship with the communities they protect. When local police coordinate with federal immigration officials, immigrants fear that if they report crimes and cooperate with the police, they will be subject to immigration enforcement and consequent deportation and separation from their families.2323. Michele Waslin, The Secure Communities Program: Unanswered Questions and Continuing Concerns (Washington, D.C.: Immigration Policy Center, 2010), 1-22 at pp.11, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/secure-communities-program-unanswered-questions-and-continuing-concerns. They are also more likely to be the victims of crimes because criminals do not expect undocumented immigrants to report wrongdoings against them because of their fear and lack of trust.24 Rachel R. Ray, “Insecure Communities: Examining Local Government Participation in US Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Secure Communities Program Immigration Enforcement: Voices for Change,” Seattle Journal for Social Justice, no. 1 (2011–2012): 325-386 at pp. 334.

A study using a sample of over one thousand adult Latina individuals in the United States found that a one-point increase in fear of deportation (measured by an increase on a scale of level of worry, such as an increase from being worried “some” to “a lot”) is associated with a 13 percent decrease in confidence that law enforcement officers would treat them fairly. Results also show that a one-point increase in fear of deportation is also associated with being 15 percent less likely to report a violent crime to law enforcement.25Messing, Jill Theresa, David Becerra, Allison Ward-Lasher, David K. Androff. “Latinas’ Perceptions of Law Enforcement,” Affilia 30, no. 3 (March 20, 2015): 328- 40 at pp. 331–34, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109915576520. This means that when local police participate in federal immigration-enforcement programs, communities and the United States at large may actually become less safe because more crimes go unpunished and victims feel more vulnerable.

Immigration experts studying immigration enforcement in other forms, rather than 287(g) or Secure Communities, found that intensifying immigration enforcement increases the likelihood that domestic violence goes unreported. A recent study assessed the relationship between increased immigration enforcement and calls dispatched to the Los Angeles Police Department between 2014 and 2017. The results show that calls related to domestic violence decreased 3 percent per capita in districts with largely undocumented immigrant populations as awareness of immigration enforcement increased.2626. Ashley N. Muchow and Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, “Immigration Enforcement Awareness and Community Engagement with Police: Evidence from Domestic Violence Calls in Los Angeles,” Journal of Urban Economics 117 (May 2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103253. Decreased reporting of domestic violence indicates that victims are unable to seek help from law enforcement when in dangerous situations. Another study showed how limiting the use of local law enforcement to implement federal immigration law shows that such policies reduced domestic-homicide victimization rates among Hispanic women by 52 to 62 percent.2727. Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes and Monica Deza, “Can Sanctuary Policies Reduce Domestic Violence?,” May 2020, The Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, 1-49, 9, 29, https://www.thecgo.org/research/can-sanctuary-policies-reduce-domestic-violence/.

Looking at evidence from Dallas shows that the introduction of PEP and narrowing targets of law enforcement reduced the cost of reporting crimes for immigrants, because under PEP, they are less likely to be detained if they are not committing a serious offense. In fact, the evidence shows that the number of incidents reported by Hispanics increased roughly 8 percent after PEP was implemented. Even more specifically, the likelihood of Hispanic victims to report violent and property crimes increased 4 percent.2828. Elisa Jacome, “The Effect of Immigration Enforcement on Crime Reporting: Evidence from the Priority Enforcement Program,” Working Paper, 2019, https://sites.google.com/view/elisajacome/research. The results confirm that focusing on the most dangerous criminals facilitates cooperation between immigrant communities and local police.

Immigration Enforcement Impacts Education

One study looks at how 287(g) programs and Secure Communities changed educational choices of Hispanic students. The study uses data on Hispanic children ages six to seventeen from 2000 to 2013. It shows that increasing immigration enforcement raises the likelihood that Hispanic students in grades K–8 will repeat a grade. In addition, and more significantly, the study also finds that more children between fourteen and seventeen years old drop out of school entirely.29Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes and Mary J. Lopez, “The Hidden Educational Costs of Intensified Immigration Enforcement: Hidden Educational Costs of Enforcement,” Southern Economic Journal 84, no. 1 (July 10, 2017): 120-154 at pp. 124–125, 131–133, 148, https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12207.

Another paper examines the effects of 287(g) programs on Hispanic student enrollment. It shows that local ICE partnerships “reduce the number of Hispanic students by 10% within 2 years.”30Thomas S. Dee and Mark Murphy. “Vanished Classmates: The Effects of Local Immigration Enforcement on School Enrollment,” American Educational Research Journal 57, no. 2 (April 2020): 694–727 at pp. 694, 708-21. doi:10.3102/0002831219860816. This may be because, when 287(g) programs are in place, parents fear that their children’s school attendance will reveal their immigration status and lead to their deportation, which in turn leads the parents to withdraw their children from the public education system. A related paper suggests that 287(g) programs may even be reducing Hispanic and Black student achievement, possibly through increased student mobility from one area to another or heightened stress.31Laura Bellows, “Immigration Enforcement and Student Achievement in the Wake of Secure Communities,” AERA Open (October 2019), 1-20. doi:10.1177/2332858419884891.

Related research examines the effect of immigration raids, rather than 287(g) programs or Secure Communities, on Hispanics’ education choices. A study of the effects of immigration raids on Head Start enrollment, for example, shows how fear of deportation arising from immigration enforcement reduces enrollment. By comparing enrollment before and after raids, the authors showed decreases in enrollment of over 10 percent. They attributed their finding to both the increased mobility among migrants and the increasing isolation among migrants who remain in their communities but choose to avoid public participation in school because they fear that doing so will divulge their immigration status and lead to their deportation.3232. Robert Santillano, Stephanie Potochnick, and Jade Jenkins, “Do Immigration Raids Deter Head Start Enrollment?,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 110 (May 1, 2020): 419-23 at pp. 419, 422–23. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20201113.

Educational attainment is an important predictor of long-term success for individuals. Educated children, whether immigrants or citizens, also make greater contributions to public budgets and economic growth in the United States. If enforcement programs reduce investment in education, they likely create long-term losses for the country as well as the local communities where immigrants live and work.

Improving Immigration-Enforcement Programs

Improving immigration-enforcement programs requires refocusing them on dangerous criminals. This means recognizing that limited resources are available for local policing. By only targeting those who threaten the safety of society, law enforcement officers would be able to rebuild trust in their communities and focus on making communities safer, not forcing immigrants to live in fear and isolation.

One way to do this is by implementing inclusive policies to integrate immigrants into American society in ways that make them feel safe in their communities. An example of an inclusive policy is sanctuary, a policy that limits how local police enforce federal immigration law. These policies give immigrants the certainty that they can work with local police officers on public-safety matters without being pursued for immigration offenses.

Research on sanctuary policies and public safety has found promising results. One study finds that crime rates did not change after the enactment of sanctuary policies. The authors concluded that sanctuary policies have “little costs for cities.”3333. Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien, Loren Collingwood, and Stephen Omar El- 5

Khatib, “The Politics of Refuge: Sanctuary Cities, Crime, and Undocumented Immigration,” Urban Affairs Review 55, no. 1 (2017): 3-40 at pp. 3-38, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1078087417704974. A similar study finds evidence that such policies result in fewer robberies but have no effects on other crimes.3434. Ricardo D. Martínez-Schuldt and Daniel E. Martínez, “Sanctuary Policies and City-Level Incidents of Violence, 1990 to 2010,” Justice Quarterly 36, no. 4 (2017): 567-593.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07418825.2017.1400577. A third study shows a large decrease in domestic homicides with Hispanic women as victims.3535. Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes and Monica Deza, “Can Sanctuary Policies Reduce Domestic Violence?”, Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, May 13, 2020, 1-40. https://www.thecgo.org/research/can-sanctuary-policies-reduce-domestic-violence A recent working paper examining 42 cities with formal sanctuary policies shows that sanctuary may reduce property crimes and does not increase overall crime rates.36Yuki Otsu, “Sanctuary Cities and Crime,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, July 30, 2020, https://www.thecgo.org/research/sanctuary-cities-and-crime. Finally, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences came to a similar conclusion. Sanctuary policies do not threaten public safety, and they reduce the number of deportations of noncriminal immigrants, potentially by as much as half.37David K. Hausman, “Sanctuary Policies Reduce Deportations without Increasing Crime,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, October 19, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014673117.

Another promising policy is community policing, which aims to develop strong relationships between community members and law enforcement. These programs allow immigrants the ability to directly work with local law enforcement officers to ensure safety in their communities. Unlike traditional law enforcement, community policing empowers individuals by creating a partnership with the local police so individuals can comfortably indicate their safety concerns.38Robert Trojanowicz and Bonnie Bucqueroux, “Community Policing the Challenge of Diversity,” National Center for Community Policing, 2010, 1-24 at pp. 14–15, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Photocopy/134975NCJRS.pdf. Evidence compiled by police-centered non-profits from Madison, Wisconsin, and Aurora, Colorado, shows that the cooperation of community members and community leaders with local law enforcement builds trust. Programs to educate officers about the cultures in their community and use different tools such as Spanish-language media to communicate with immigrant communities demonstrate how the relationship between immigrants and law enforcement can be positive and long-lasting.3939. Police Executive Research Forum, “Community Policing in Immigrant Neighborhoods: Stories of Success,” Police Executive Research Forum, 2019, 1-85 at pp.47–48, https://www.policeforum.org/assets/ CommunityPolicingImmigrantNeighborhoods.pdf.

Fostering a better relationship between immigrants and local law enforcement officers would help address crime without instilling fear in immigrant populations or harming those who could contribute to growing the US economy. Policymakers should reconsider policies that emphasize targeting immigrant populations and instead favor policies that promote inclusive communities.