The number of private school choice options has continued to grow ever since 1990, when the first modern-day school choice program in the United States was established in Milwaukee. Today, 65 private school choice programs are in operation in 29 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. These include vouchers, tax credit scholarships, and education savings accounts.1EdChoice, The ABCs of School Choice: The Comprehensive Guide to Every Private School Choice Program in America, 2020 ed. During the Trump administration, officials put a renewed spotlight on school choice using the bully pulpit to make the case for its efficacy, signing into law a reauthorization of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program, and in its push for a federal tax credit scholarship program. Increased interest in, and availability of, private school choice programs raises questions about the extent to which these programs will generate a genuine variety of education options for families. Growth in school choice programs has also generated a debate about the extent to which these programs should be regulated, the form regulations should take, and whether regulations increase or impede the quantity and quality of education options available to families.

Private school choice programs enable families to move from public schools to private schools and to access other education products and services. Many families do so because they are looking for something not offered in the public-school sector, and believe that the private-education sector offers something different that will better suit the needs of their child. Government regulations, in the form of oversight provided through mechanisms such as state standardized testing, are appropriate for providing accountability in the public sector, since public schools are accountable to government officials and are less-directly accountable to parents.2Jason Bedrick, “Leave School Choice to the States,” TownHall.com, April 16, 2015. But government regulations designed to hold the public system accountable are inappropriate for a system of private education, which is supposed to offer something different to families than the public system, and which is held to an arguably higher form of accountability: the market.3Bedrick, “Leave School Choice to the States.” Families that are unhappy with any element of their child’s private school can vote with their feet and leave—an exit option that is more difficult for most families to execute in the residentially assigned public school system. Nevertheless, some scholars have made the moral case for government regulation of the private sector.

Former Hoover Institution research fellow Tibor Machan argued that there is a fundamental difference between government management and government regulation, contrasting national forests and parks and highways, which are government managed, with food and drug production, car sales, toy production, and so on, which are government regulated, but not managed.4Tibor R. Machan, “Government Regulation of Business: The Moral Arguments,” Foundation for Economic Education, July 1, 1988. Private schooling falls into the latter category: private schools are privately managed and operated, but exist within a patchwork quilt of regulatory environments in the states. Moral cases for government regulation of the private sector have generally taken four forms: (1) Private corporations are chartered by the states in which they reside, and thus the government has a foothold to regulate the behavior of private entities. (2) Market failures—that is, instances when the market “fails to achieve maximum efficiency”—can produce waste.5Machan, “Government Regulation of Business.” (3) Government regulations are needed to protect individual rights. And (4) there is sometimes judicial inefficiency—as seen, for example, in the adjudication of disputes involving pollution.6Machan, “Government Regulation of Business.”

Proponents of the regulation (sometimes referred to as accountability) of private school choice programs tend broadly to appeal to these moral arguments for government regulation of private entities. They argue that government “open admissions” regulations are necessary to ensure that private schools participating in school choice programs accept all students who apply, that the government should cap how much tuition a private school can charge so that it will not exceed the voucher amount and families on a scholarship can be guaranteed to afford it; that the government should require accreditation and standardized testing to ensure quality among participating schools. Moreover, proponents of private school choice regulations argue that such regulations are more likely to deter lower-performing schools from participating and therefore to increase the average quality of the private schools that participate.7Douglas Harris, “The Reform Debate, Part II: The Difference between Charter and Voucher Schools,” Education Week, November 11, 2015.

This chapter examines these arguments, with a particular emphasis on the Louisiana Scholarship Program—the most heavily regulated private school choice program in the country, and the only private school choice program that has produced negative academic outcomes for participants. We begin by looking at the experimental research on the impact of school choice broadly on academic achievement and attainment. Next, we review the literature on the impact of regulations on the quantity and quality of private schools in school choice programs. We conclude with a discussion of implications for federal and state policy.

Background to the Research Literature

We review the literature on the impact of regulations on private school choice programs. Our review strategy was twofold: First we gathered the universe of randomized controlled trial evaluations examining the impact of private school choice on student educational outcomes, including academic achievement and attainment. These randomized controlled trials include 16 studies on student academic achievement, published between 1998 (the first such evaluation ever conducted) and 2019 (the most recent evaluation published). Next we surveyed the correlational and descriptive literature on the impact of regulations on the supply of private schools and their quality, within the context of private school choice programs. We have included quantitative studies (seven studies), which use data to assess the types of schools that do or do not participate in voucher programs, and qualitative studies (eight studies), to understand the types of private schools that elect to participate in choice programs.

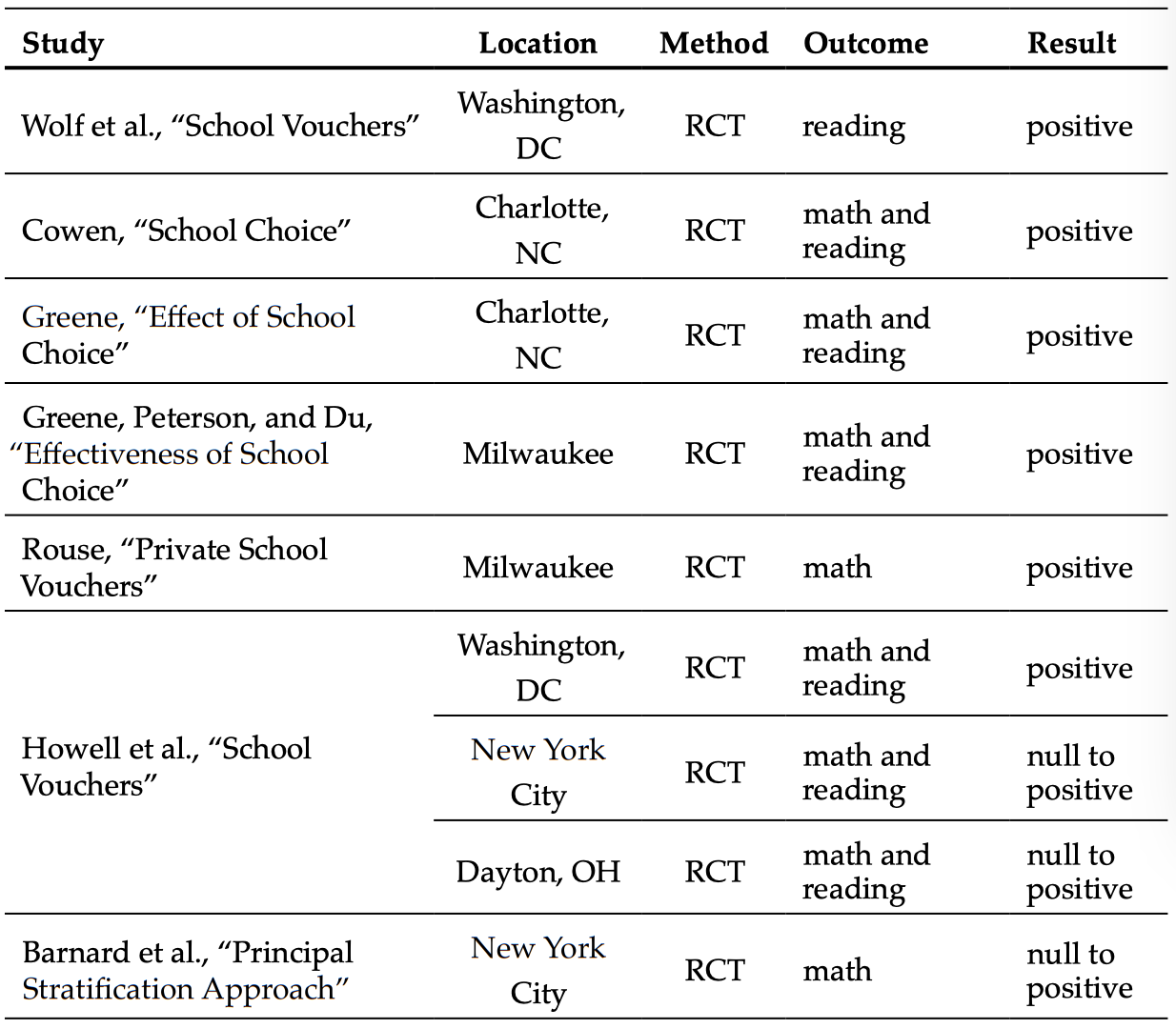

As shown in table 1, most evaluations of private school choice programs suggest that school choice indeed leads to higher test scores for students overall or for student subgroups.8 John Barnard et al., “Principal Stratification Approach to Broken Randomized Experiments: A Case Study of School Choice Vouchers in New York City,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 98, no. 462 (2003): 299–323; Joshua M. Cowen, “School Choice as a Latent Variable: Estimating the ‘Complier Average Causal Effect’ of Vouchers in Charlotte,” Policy Studies Journal 36, no. 2 (2008): 301–15; Jay P. Greene, Paul E. Peterson, and Jiangtao Du, “Effectiveness of School Choice: The Milwaukee Experiment,” Education and Urban Society 31, no. 2 (1999): 190–213; Jay P. Greene, “The Effect of School Choice: An Evaluation of the Charlotte Children’s Scholarship Fund Program,” Civic Report 12 (2000): 1–15; William G. Howell et al., “School Vouchers and Academic Performance: Results from Three Randomized Field Trials,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21, no. 2 (2002): 191–217; Hui Jin, John Barnard, and Donald B. Rubin, “A Modified General Location Model for Noncompliance with Missing Data: Revisiting the New York City School Choice Scholarship Program Using Principal Stratification,” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 35, no. 2 (2010): 154–73; Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Private School Vouchers and Student Achievement: An Evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 2 (1998): 553–602; Patrick J. Wolf et al., “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32, no. 2 (2013): 246–70.

Table 1. Effect of Private School Choice on Math and Reading Test Scores

*Statistically significant positive effects are detected for subgroups.

Note: RCT = randomized controlled trial. ”Positive” means that the study indicates a statistically significant test score benefit of private school choice overall. “Negative” means that the study finds a statistically significant negative effect of private school choice on test scores overall. “Null” indicates that the overall result reported for the outcome is not statistically significant. “Null to positive” means that statistically significant positive effects are detected for subgroups. Research on existing school voucher programs in Indiana and Ohio also found null to negative impacts on the academic achievement outcomes of participating students. These two studies, however, are not included because they are observational and cannot demonstrate that the negative outcomes were caused by voucher program participation.

Sources: Patrick J. Wolf et al., “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32, no. 2 (2013): 246–70; Joshua M. Cowen, “School Choice as a Latent Variable: Estimating the ‘Complier Average Causal Effect’ of Vouchers in Charlotte,” Policy Studies Journal 36, no. 2 (2008): 301–15; Jay P. Greene, “The Effect of School Choice: An Evaluation of the Charlotte Children’s Scholarship Fund Program,” Civic Report 12 (2000): 1–15; Jay P. Greene, Paul E. Peterson, and Jiangtao Du, “Effectiveness of School Choice: The Milwaukee Experiment,” Education and Urban Society 31, no. 2 (1999): 190–213; Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Private School Vouchers and Student Achievement: An Evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 2 (1998): 553–602; William G. Howell et al., “School Vouchers and Academic Performance: Results from Three Randomized Field Trials,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21, no. 2 (2002): 191–217; John Barnard et al., “Principal Stratification Approach to Broken Randomized Experiments: A Case Study of School Choice Vouchers in New York City,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 98, no. 462 (2003): 299–323; Hui Jin, John Barnard, and Donald B. Rubin, “A Modified General Location Model for Noncompliance with Missing Data: Revisiting the New York City School Choice Scholarship Program Using Principal Stratification,” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 35, no. 2 (2010): 154–73; Alan B. Krueger and Pei Zhu, “Another Look at the New York City School Voucher Experiment,” American Behavioral Scientist 47, no. 5 (2004): 658–98; Marianne Bitler et al., “Distributional Analysis in Educational Evaluation: A Case Study from the New York City Voucher Program,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 8, no. 3 (2015): 419–50; Eric Bettinger and Robert Slonim, “Using Experimental Economics to Measure the Effects of a Natural Educational Experiment on Altruism,” Journal of Public Economics 90, no. 8–9 (2006): 1625–48; Ann Webber et al., Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts Three Years after Students Applied, NCEE 2019-4006 (National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, US Department of Education, 2019); Jonathan N. Mills and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement after Four Years” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-10, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, 2019); Atila Abdulkadiroğlu, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “Free to Choose: Can School Choice Reduce Student Achievement?,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, no. 1 (2018): 175–206.

Explanations for the Negative Results

What might explain the LSP’s negative effects on student test scores? Although the LSP is not the sole private school choice program to produce negative impacts on student academic achievement, it is the only program for which an experimental evaluation has demonstrated a causal effect. However, it is important to first provide some broader context for the overall evidence (including nonexperimental evaluations) on the impact of private school choice programs on student academic achievement.

Research on existing school voucher programs in Indiana and Ohio also found negative impacts on the academic achievement outcomes of participating students. A matching study (comparing students in Indiana’s voucher program to a closely matched sample of their public school peers) found that Indiana’s private school voucher program, currently serving some 34,000 students, led to a reduction in math achievement of 15 percent of a standard deviation after the students initially entered the voucher program, but that the students’ math performance improved in later years. The researchers found no significant effect on English language arts performance.14R. Joseph Waddington and Mark Berends, “Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement Effects for Students in Upper Elementary and Middle School,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37, no. 4 (2018): 783–808. Notably, the 2017 working paper version of this same evaluation found no effects on math and marginally significant positive effects on reading after four years.15R. Joseph Waddington and Mark Berends, “Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement Effects for Students in Upper Elementary and Middle School” (working paper, 2017). This change in results after the peer-review process reinforces our decision to focus on randomized controlled trials rather than matching evaluations. Matching studies are less rigorous and possibly prone to bias introduced by the model specification decisions made by researchers.

A similarly structured matching study examining the impact of the Ohio EdChoice scholarship program on student academic achievement found that students who used a scholarship to attend a private school of choice performed worse in math and English than their matched peers who attended public schools.16David Figlio and Krzysztof Karbownik, Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, Competition, and Performance Effects (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2016). Although this study found negative achievement effects on student academic achievement, it found positive competitive effects on test scores for students in nearby public schools.

Understanding the research in Indiana and Ohio provides important, but limited, context. Both of these states regulate their private school choice programs, though not to the extent that Louisiana regulates its program. Perhaps not consequently, the percentage of private schools that participate is higher in Ohio and Indiana than in Louisiana.17Corey A. DeAngelis, “Regulatory Compliance Costs and Private School Participation in Voucher Programs,” Journal of School Choice 14, no. 1 (2020): 95–121. But readers should be cautious in interpreting the findings from Indiana and Ohio, because the existing studies on the impact of these school voucher programs are arguably correlational, and regulations are just one possible explanation for negative effects.

The strongest theories explaining the causal studies showing negative effects—the research concerning Louisiana—have to do with curriculum misalignment and the burdensome regulations on private schools participating in the program. First, there could be a curriculum alignment problem. Private schools have weaker incentives to teach to the test and less experience with the state’s preferred curriculum than public schools. That being so, using vouchers to enable students to attend a private school could decrease their standardized test scores without actually reducing their cognitive skills. At the same time, recent empirical evidence suggests that the theory of curricular misalignment has merit. Researchers have found that private schools are more concerned about state standardized testing mandates than requirements to take nationally norm-referenced exams.18Brian Kisida, Patrick J. Wolf, and Evan Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools: Attitudes about School Choice Programs in Three States (American Enterprise Institute, January 2015). In addition, a survey experiment has found that state testing mandates largely reduce anticipated participation in voucher programs, while nationally norm-referenced testing mandates have no statistically significant effect.19Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from California and New York” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-07, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, 2019). Furthermore, every experimental voucher program evaluation following students for at least three years has found neutral to positive effects on test scores; the only exception is the LSP, which requires private schools to administer the state test.

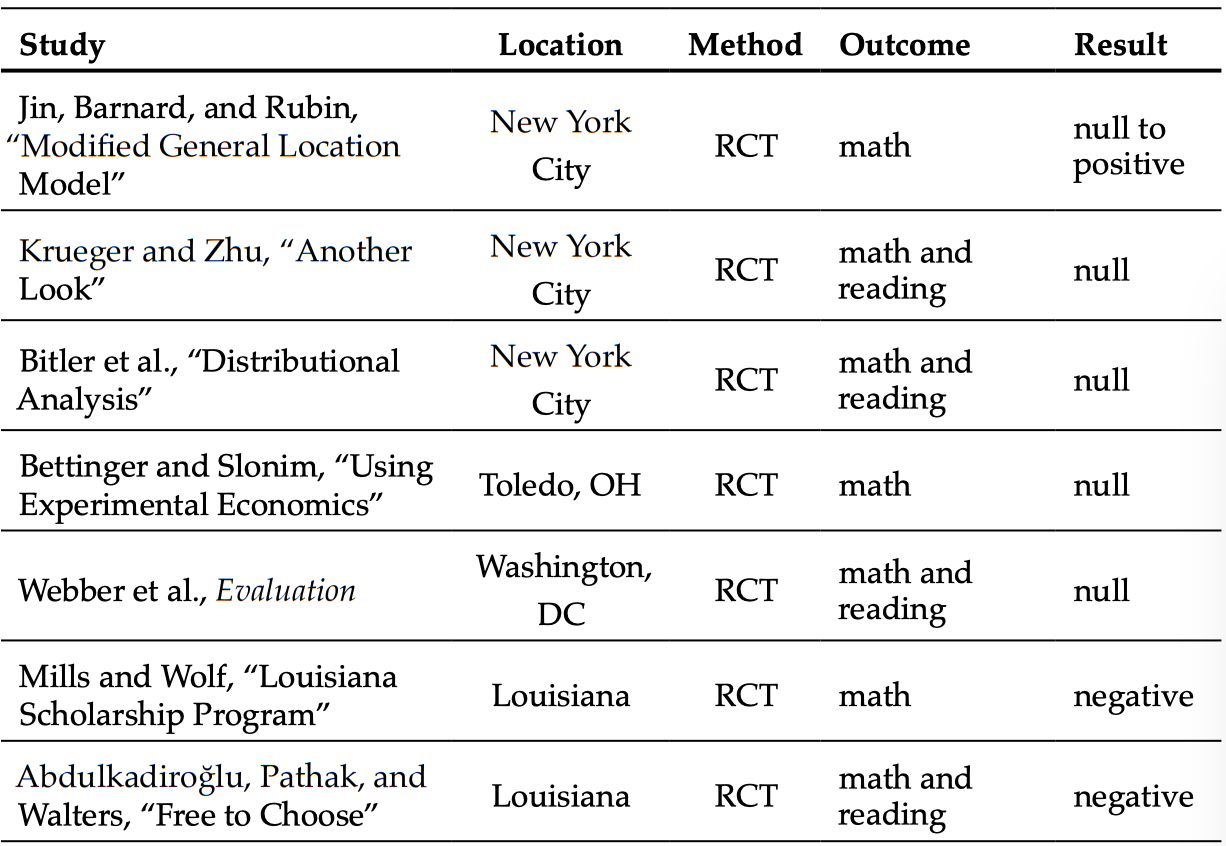

Second, regulations might be responsible for the negative effects. Private schools participating in the LSP must administer the state standardized test, admit students on a random basis (open-admissions), and accept the voucher funding amount as payment in full (see table 2). The large negative effects of the LSP on math test scores persisted after four years of participation—a period that should have given private schools adequate time to adjust to new students and tests. Some education scholars have argued that the negative effects would have been even worse in Louisiana if not for the program’s quality-enhancing regulations—after all, they argued, the highest-quality private schools should be the most likely to not participate in the program regardless of the regulatory burden, because they want to remain exclusive.20Harris, “Reform Debate, Part II.” In these scholars’ view, program regulations are more likely to deter lower-quality schools from participating in the program, and therefore increase the average quality of private schools that participate.

On the other hand, lower-quality private schools might be more likely to participate in the program regardless of the regulatory burden, because they are the most desperate for additional enrollment and funding.21Jason Bedrick, “The Folly of Overregulating School Choice,” Education Next, January 5, 2016. Higher-quality private schools might be more likely to be deterred by regulations if they can afford to turn down the voucher funding and wish to remain autonomous and specialized. If so, voucher program regulations can be expected to decrease the average quality of private schools that participate. Some scholars have found, for example, that random-admissions mandates and state testing mandates are negatively associated with program participation. A 2020 study leveraged data from the 2015/16 Private School Universe Survey and found that both state testing requirements and open-admissions mandates depressed private school program participation across seven locations.22DeAngelis, “Regulatory Compliance Costs.”

Both sides of the debate tend to agree that program regulations reduce the quantity of schools that accept voucher students, since regulations are costs associated with participation.23Harris, “Reform Debate, Part II.” Moreover, regulations such as state standardized testing requirements and random-admissions mandates might be particularly costly for the most specialized schools. If matching the unique needs of students to schools affects program success, regulations might reduce the effectiveness of voucher programs simply by reducing the number of specialized options available to families.

Table 2. Private School Choice Program Characteristics

a School must be accredited within three years of initial program participation.

b Parents of students in grades 9–12 with an income greater than 220 percent of the federal poverty level may be charged additional tuition above the voucher amount.

c Copay is prohibited for students from families that are at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Note: MPCP = Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, WPCP = Wisconsin Parental Choice Program, CSP = Choice Scholarship Program, LSP = Louisiana Scholarship Program, OSP = Opportunity Scholarship Program. Eligibility rate means the percent of families living in the area that have students who are eligible for the program. Private school participation rate means the percentage of private schools participating in the programs. Copay prohibited refers to the practice that a voucher must be accepted as payment-in-full.

Source: Corey A. DeAngelis, “Which Schools Participate? An Analysis of Private School Voucher Program Participation Decisions across Seven Locations” (working paper, 2019), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3309754.

Finally, although it doesn’t explain the negative effects, the program might improve character skills that are simply not captured by standardized math and reading tests. If so, standardized test scores might not be strong proxies for long-term outcomes such as college enrollment and degree attainment. In fact, two recent reviews of the evidence find that schools’ effects on students’ test scores often do not predict schools’ effects on students’ long-term outcomes. The authors of the first study compile all the evidence linking choice schools’ effects on test scores and attainment and find that “a school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impact on longer-term outcomes.”24Hitt, McShane, and Wolf, “Do impacts on test scores even matter? Lessons from long-run outcomes in school choice research” (American Enterprise Institute, 2018). For example, the study finds that 61 percent of schools’ effects on math test scores—and 50 percent of their effects on reading test scores—did not successfully predict their effects on high school graduation. The second study similarly reviewed 11 studies indicating disconnects between private schools’ effects on standardized test scores and their effects on long-term outcomes such as crime and college enrollment.25Corey A. DeAngelis, “Divergences between Effects on Test Scores and Effects on Non-cognitive Skills,” Educational Review 2019.

But what does the evidence say? For the first time, we review the empirical evidence on the effects of school choice program regulations. Specifically, the preponderance of the evidence suggests that regulations are associated with reductions in the quantity, quality, and specialization of private schools participating in such programs. These unintended consequences could partially explain the recent negative effects of certain school choice programs on student achievement. Decreasing certain program regulations could improve the effectiveness of private school choice programs by increasing the number of meaningful options available to the families that need them the most.

Review Findings

We use the following inclusion criteria for reviewing the evidence linking private school choice program regulations to the quantity, quality, and specialization of participating private schools:

- quantitative studies (which use data to assess the types of schools that do or do not participate in voucher programs)

- studies that examine at least one of three outcomes: the quantity, quality, or specialization of private schools participating in choice programs

Quantity

Regulations could have negative effects on the supply of private schools available to families.26Frederick M. Hess, “Does School Choice ‘Work’?,” National Affairs 5, no. 1 (Fall 2010): 35–53; Michael Q. McShane, ed., New and Better Schools: The Supply Side of School Choice (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015). Private school leaders weigh costs and benefits when deciding whether to participate in private school choice programs each year. Because regulations are additional costs associated with participation, regulations should decrease the number of private schools that participate in choice programs.

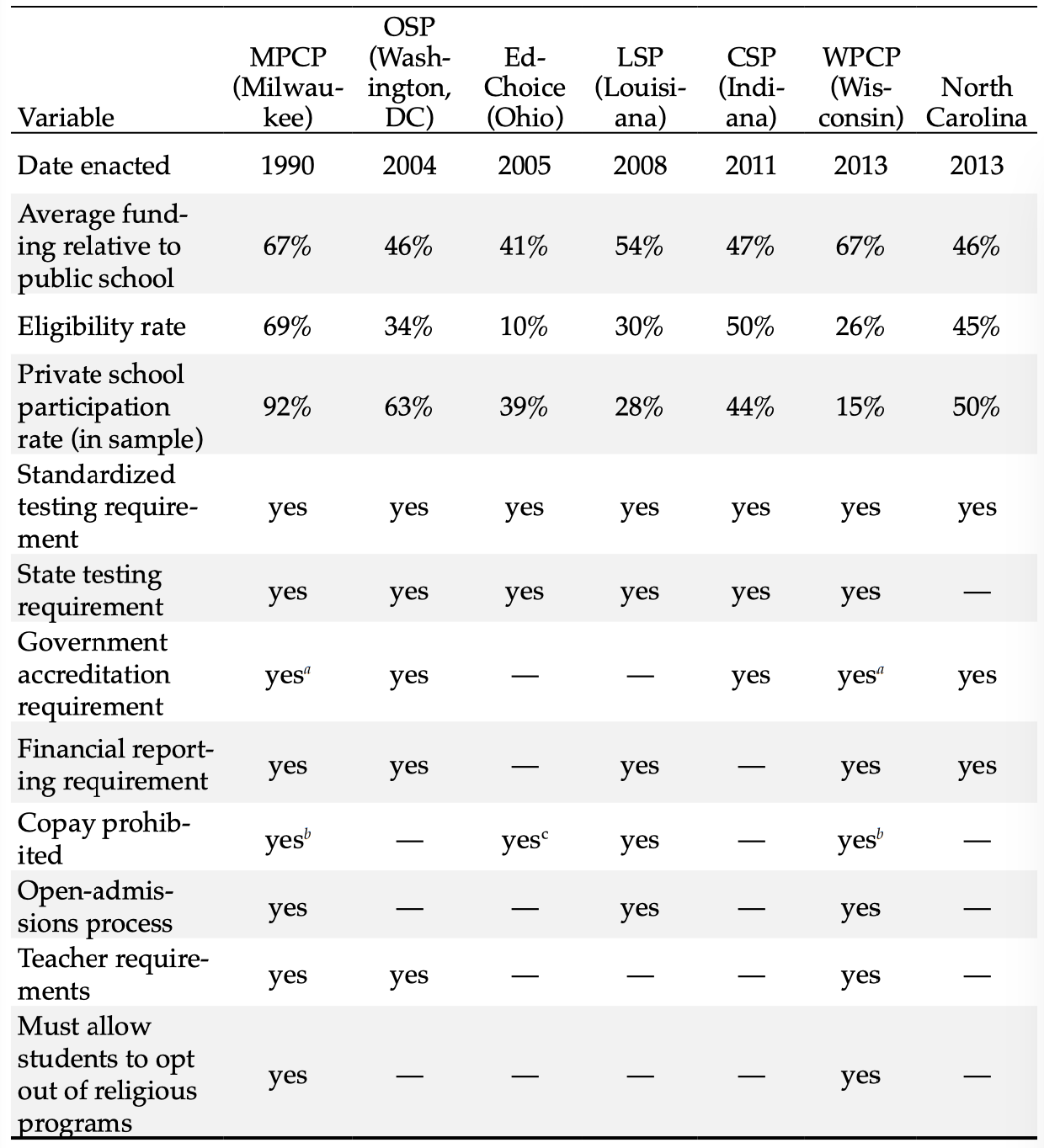

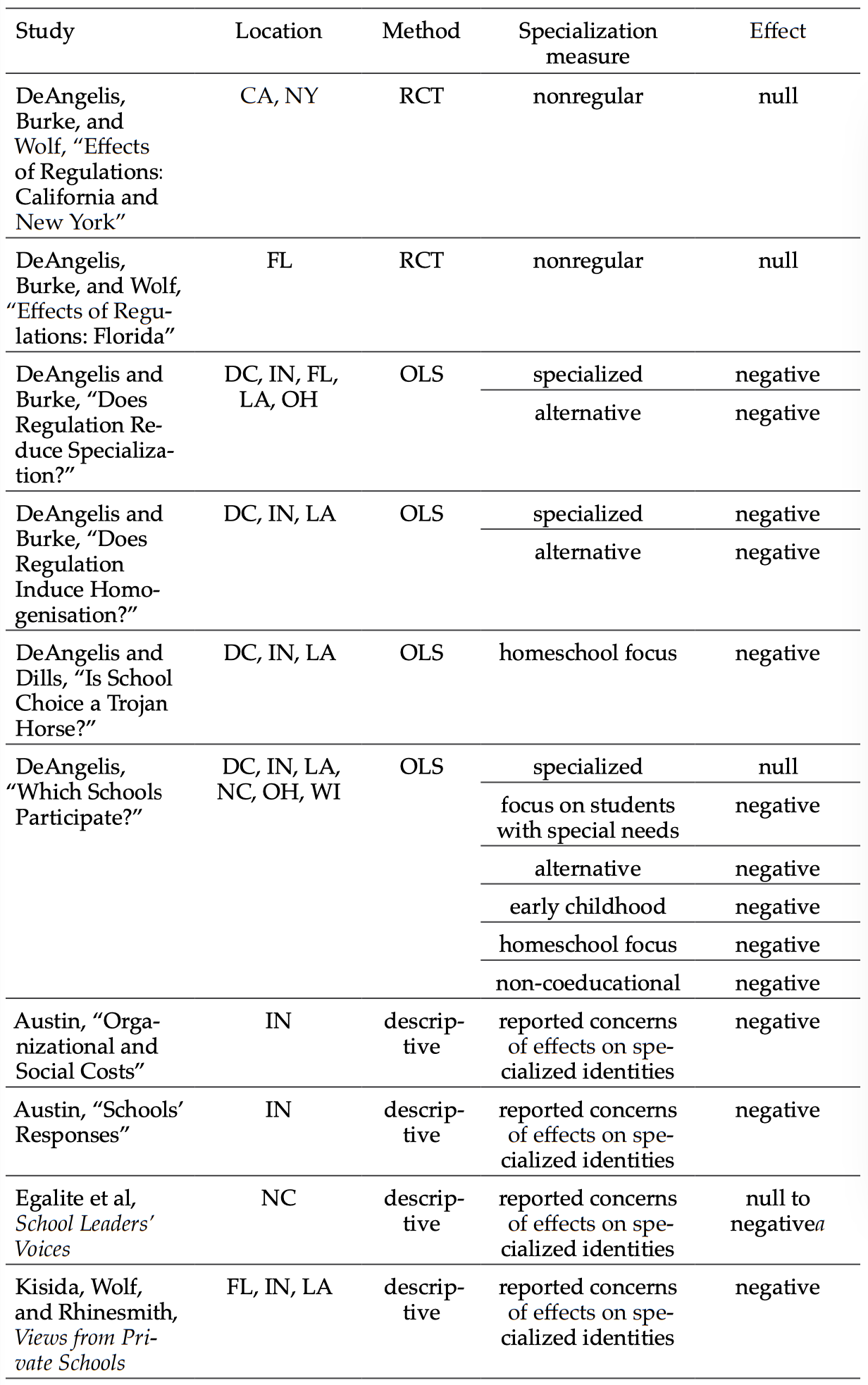

The limited evidence on the subject supports this theory. Most of the literature linking regulations to the quantity of private schools participating in school choice programs is either correlational or merely descriptive (see table 3). Three descriptive studies examining private school choice programs in Indiana, North Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana find that private school leaders are concerned with current or future program regulations.

Megan Austin, senior researcher at American Institutes for Research, finds that the private schools electing to participate in Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program (CSP) are most concerned about how regulations would affect their academic and religious identities. Indeed, Austin finds that schools participating in the CSP experience changes to the religious and academic composition of their students, as anticipated.27Megan J. Austin, “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy: Participation Decisions and Early Implementation Experiences in the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program,” Journal of School Choice 9, no. 3 (2015): 354–79. Austin also finds that private schools not participating in the CSP are most concerned about the program’s procedural requirements.28Austin, “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy.”

The authors of a report evaluating North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship find that the top concern for private schools participating in the program is future regulations. (Eighty-two percent of the participating schools list future regulations as a concern). Regulations are also the top reason private school leaders list for declining to participate in the program. (Fifty-seven percent of nonparticipating schools list future regulations as a concern.)29Anna J. Egalite et al., School Leaders’ Voices: Private School Leaders’ Perspectives on the North Carolina Opportunity Scholarship Program, 2018 Update, OS Evaluation Report #6 (NC State College of Education, October 2018).

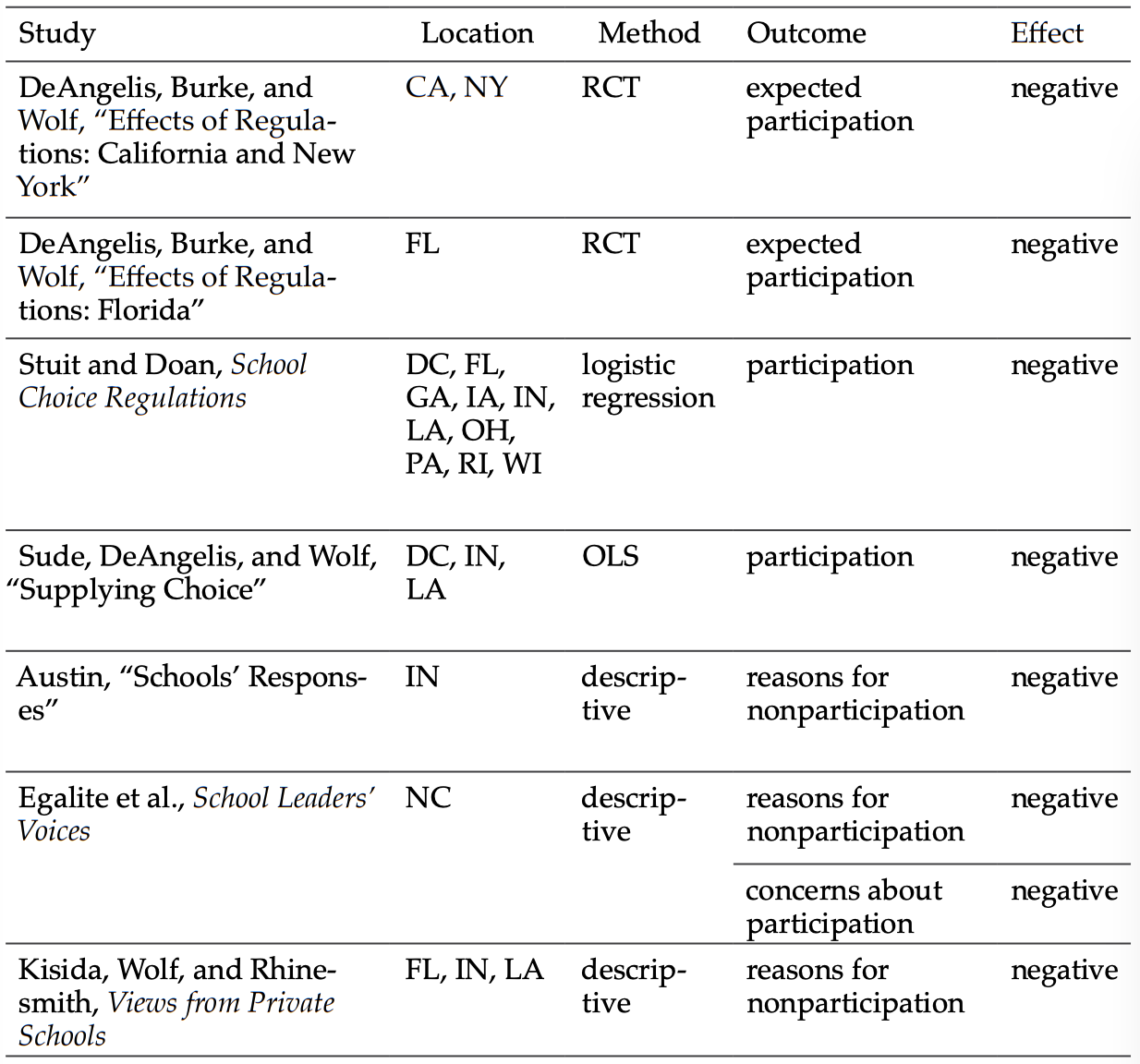

Table 3. Effect of School Choice Regulations on Private School Participation Decisions

Note: RCT = randomized controlled trial, OLS = ordinary least squares regression. ”Negative” indicates that the study found a statistically significant negative relationship between program regulations and private school participation.

Sources: Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from California and New York” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-07, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, 2019); Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from Florida,” Social Science Quarterly 100, no. 6 (2019), 2316–36; David Stuit and Sy Doan, School Choice Regulations: Red Tape or Red Herring? (Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2013); Yujie Sude, Corey A. DeAngelis, and Patrick J. Wolf, “Supplying Choice: An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Voucher Programs in Washington, DC, Indiana, and Louisiana,” Journal of School Choice 12, no. 1 (2018): 8–33; Megan J. Austin, “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy: Participation Decisions and Early Implementation Experiences in the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program,” Journal of School Choice 9, no. 3 (2015): 354–79; Anna J. Egalite et al., School Leaders’ Voices: Private School Leaders’ Perspectives on the North Carolina Opportunity Scholarship Program, 2018 Update, OS Evaluation Report #6 (NC State College of Education, October 2018); Brian Kisida, Patrick J. Wolf, and Evan Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools: Attitudes about School Choice Programs in Three States (American Enterprise Institute, January 2015).

The authors of a 2015 study surveyed the leaders of nonparticipating private schools in Florida, Indiana, and Louisiana.30Kisida, Wolf, and Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools. The researchers found that 64 percent of leaders of nonparticipating private schools in Louisiana, 62 percent in Indiana, and 26 percent in Florida listed “future regulation that might come with participation” as a major reason for nonparticipation. In addition, they found that leaders participating in the LSP—the most heavily regulated of the three locations—are the most concerned about future regulations.31Kisida, Wolf, and Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools. In fact, 100 percent of the leaders of private schools participating in the LSP reported that future regulations are a general concern and 64 percent reported that future regulations are a major concern. Fifty-four percent of private school leaders participating in the CSP reported that future regulations are a major concern, while 44 percent of private school leaders participating in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program—the least-regulated program of the three—reported future regulations as a major concern.

A 2018 study shows that only a third of the private schools in Louisiana participate in the heavily regulated LSP, whereas over twice that proportion of private schools participate in less-regulated programs in Washington, DC, and Indiana.32Yujie Sude, Corey A. DeAngelis, and Patrick J. Wolf, “Supplying Choice: An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Voucher Programs in Washington, DC, Indiana, and Louisiana,” Journal of School Choice 12, no. 1 (2018): 8–33. Co-founder of Basis Policy Research, David Stuit, and Associate Policy Researcher at RAND Corporation, Sy Doan, use school-level data from the 2009/10 round of the Private School Universe Survey to examine the relationship between school choice program regulatory burden and private school participation in school choice programs.33David Stuit and Sy Doan, School Choice Regulations: Red Tape or Red Herring? (Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2013). After controlling for other factors that might influence a school’s decision to participate—such as school size, urbanicity, religiosity, and enrollment trends—Stuit and Doan find that increases in regulatory burdens are associated with decreases in private school participation rates. Specifically, the authors find that an increase in the regulatory burden score from 10 to 75 is associated with a 9 percentage point decrease in the likelihood of private school participation.34Stuit and Doan, School Choice Regulations.

Most studies examining the effects of school choice regulations are descriptive because regulations are not randomly assigned to private schools. Furthermore, the correlational literature is limited because regulatory packages are relatively similar across programs and tend not to change much over time. Two survey experiments attempt to establish causal relationships between specific voucher program regulations and private school participation. They use surveys to randomly assign different regulations—or a control condition—to private school leaders in three different states and ask them whether they would participate in new private school choice programs during the following school year.35Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from Florida,” Social Science Quarterly 100, no. 6 (2019), 2316–36; DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: California and New York.” The first experiment surveys private school leaders in Florida and finds that the open-admissions mandate reduces the likelihood that private school leaders say they are “certain to participate” by about 17.4 percentage points, while state standardized testing requirements reduce the likelihood that private school leaders say they are “certain to participate” by about 11.6 percentage points.36DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: Florida.” Similarly, the second surveys private school leaders in California and New York and find that the open-admissions mandate reduces certain participation by about 19 percentage points, while state standardized testing requirements reduce certain participation by about 9 percentage points.37DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: California and New York.” However, neither experimental study finds evidence that nationally norm-referenced testing requirements or the prohibition of parental copayment reduce private school participation overall.38The literature on this topic has important limitations. The two survey experiments are limited because they draw conclusions on the basis of stated—rather than revealed—preferences. See Paul A. Samuelson, “Consumption Theory in Terms of Revealed Preference,” Economica 15, no. 60 (1948): 243–53. The nonexperimental studies are limited because they are merely correlational.

Quality

In theory, regulations might be less likely to deter lower-quality private schools from participating in school choice programs than higher-quality private schools, since lower-quality schools are more in need of additional funding and enrollment—and, thus, more open to adhering to a regulatory regime in order to secure additional revenue. For their part, higher-quality private schools might be more selective when it comes to the types of voucher programs they opt into, since they are less likely to need the additional revenues to stay afloat.

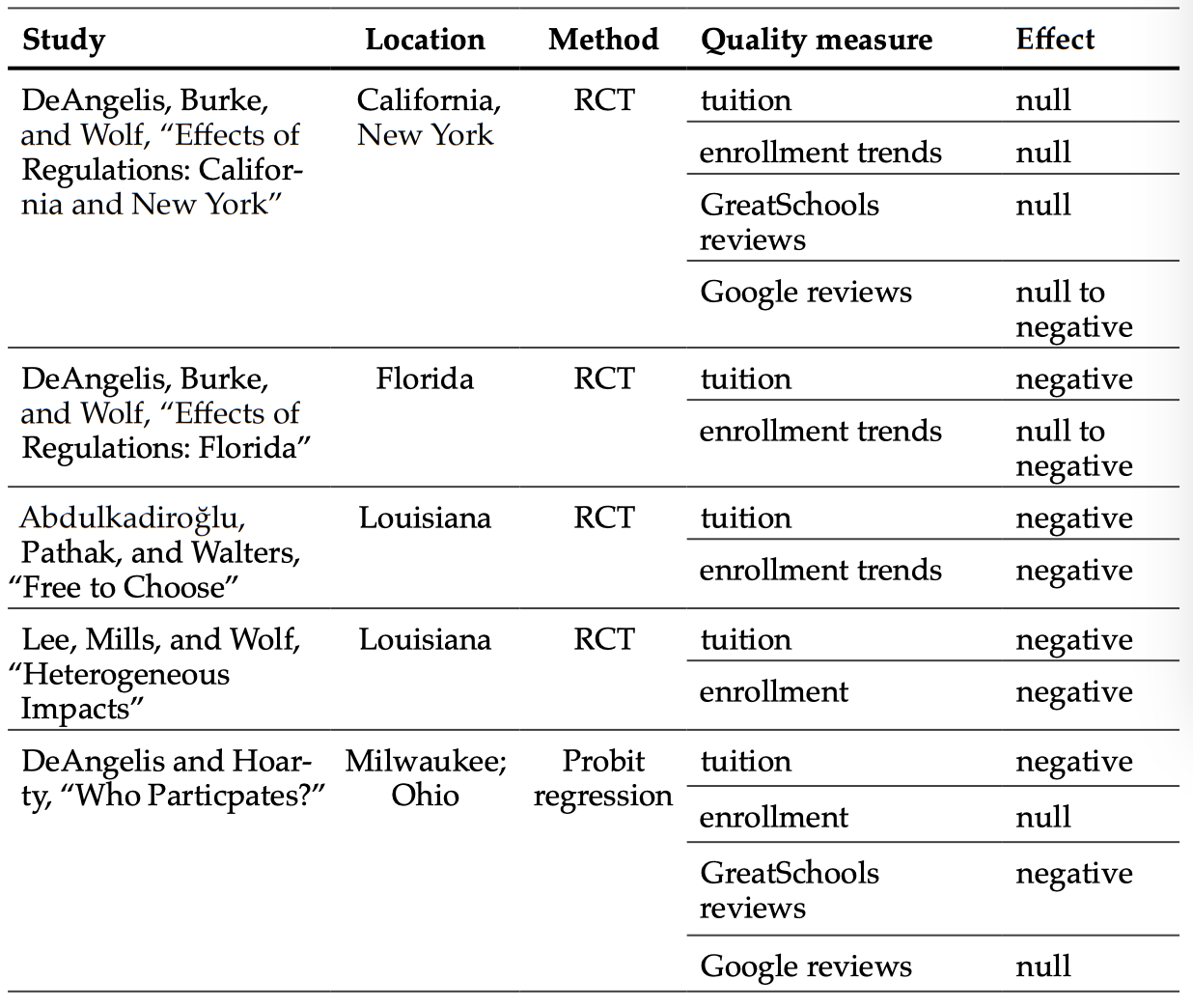

The research on this question is limited since school quality is difficult to define, particularly because it is multidimensional. Families choose schools for their children on the basis of numerous priorities, including safety, culture, civic skills, religiosity, peer groups, location, and standardized test scores, among other factors. That said, eight empirical evaluations have examined the types of private schools that elect to participate in choice programs using six different measures of quality: tuition, enrollment, Google review scores, GreatSchools review scores, school safety, and standardized test scores. The preponderance of the evidence suggests that schools judged to be lower quality—on the basis of these six metrics—tend to be more likely to participate in choice programs (see table 4).

A 2018 study finds that schools with higher tuitions, enrollments, and GreatSchools review scores are less likely to participate in the Louisiana voucher program; however, the result for GreatSchools review scores is not statistically significant.39Sude, DeAngelis, and Wolf, “Supplying Choice.” Two random assignment evaluations of the LSP find that the overall negative effects of the program are largely driven by private schools with lower tuition levels and enrollment trends,40Abdulkadiroğlu, Pathak, and Walters, “Free to Choose”; Matthew H. Lee, Jonathan N. Mills, and Patrick J. Wolf, “Heterogeneous Impacts across Schools in the First Four Years of the Louisiana Scholarship Program” (EDRE Working Paper 2019-11, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, Fayetteville, AR, April 23, 2019). suggesting that these two measures are also valid proxies for test score value-added. Furthermore, tuition levels represent the price customers are willing to pay for a school’s bundle of education services, while enrollment represents the quantity of a school’s education services demanded by families. Three other correlational studies indicate that schools with higher levels of tuition, larger enrollment, higher customer reviews, greater safety, and greater test score value-added tend to be less likely to participate in voucher programs in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ohio; Indiana; Colombia; and Chile.41Eric Bettinger et al., “School Vouchers, Labor Markets and Vocational Education” (Borradores de Economía No. 1087, Banco de la República, Colombia, 2019); Corey A. DeAngelis and Blake Hoarty, “Who Participates? An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Two Voucher Programs in the United States” (Policy Analysis No. 848, Cato Institute, 2018); Corey A. DeAngelis and Martin F. Lueken, “Are Choice Schools Safe Schools? A Cross-Sector Analysis of K–12 Safety Policies and School Climates in Indiana” (Working Paper 2019-2, EdChoice, April 3, 2019); Cristián Sánchez, “Understanding School Competition under Voucher Regimes” (working paper, September 17, 2018), http://econweb.umd.edu/~sanchez/files/csanchez_jmp.pdf.

Although most of the correlational evidence indicates that lower-quality private schools tend to be more likely to participate in school choice programs, these studies cannot establish that program regulations are actually responsible. However, regulations are the largest cost associated with participation, in theory, and private school leaders report that program regulations are major deterrents.42Egalite et al., School Leaders’ Voices; Kisida, Wolf, and Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools. Only two studies have randomly assigned regulations—or a control condition—to private school leaders using a survey.43DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: Florida”; DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: California and New York.” One of these experiments finds limited evidence to suggest that higher-quality private schools in Florida are more likely to be deterred by various regulations.44DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: Florida.”

The clearest result of this experiment is that more expensive schools are more likely to be deterred by the regulation mandating that all schools accept the voucher amount as full payment. This result is intuitive: it is much more costly for a school with tuition of $20,000 to accept a $6,000 voucher as payment in full than for a school with tuition of $10,000 to do so. In addition, the researchers’ model, with all controls, finds that a $1,000 increase in tuition is associated with a 1.4 percentage point increase in the magnitude of the negative effect of a state standardized testing mandate on intended program participation. The researchers also find that a 10 percentage point increase in enrollment growth from 2014 to 2016 is associated with a 2 percentage point increase in the magnitude of the negative effect of the open-admissions regulation on intended program participation.

The survey experiment examining the relationship between regulations and private school participation in voucher programs in California and New York mostly does not find heterogeneous effects by school quality. However, one marginally significant result suggests that a one-point increase in Google review scores (on a five-point rating scale) is associated with a 14.5 percentage point increase in the magnitude of the negative effect of the state testing mandate on anticipated program participation.

Table 4. Effect of School Choice Regulations on Quality of Participating Private Schools

Note: RCT = randomized controlled trial, OLS = ordinary least squares regression. “Negative” indicates that the study found a statistically significant negative relationship between program regulations and the quality of the participating private schools. “Null” indicates that the study found no relationship between program regulations and the quality of the participating private schools. “Null to negative” indicates that the study found null to negative relationships between program regulations and the quality of the participating private schools.

Sources: Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from California and New York” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-07, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, 2019); Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from Florida,” Social Science Quarterly 100, no. 6 (2019), 2316–36; Atila Abdulkadiroğlu, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “Free to Choose: Can School Choice Reduce Student Achievement?,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, no. 1 (2018): 175–206; Matthew H. Lee, Jonathan N. Mills, and Patrick J. Wolf, “Heterogeneous Impacts across Schools in the First Four Years of the Louisiana Scholarship Program” (EDRE Working Paper 2019-11, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, Fayetteville, AR, April 23, 2019); Corey A. DeAngelis and Blake Hoarty, “Who Participates? An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Two Voucher Programs in the United States” (Policy Analysis No. 848, Cato Institute, 2018); Corey A. DeAngelis and Martin F. Lueken, “Are Choice Schools Safe Schools? A Cross-Sector Analysis of K–12 Safety Policies and School Climates in Indiana” (Working Paper 2019-2, EdChoice, April 3, 2019); Eric Bettinger et al., “School Vouchers, Labor Markets and Vocational Education” (Borradores de Economía No. 1087, Banco de la República, Colombia, 2019); Cristián Sánchez, “Understanding School Competition under Voucher Regimes” (working paper, September 17, 2018), http://econweb.umd.edu/~sanchez/files/csanchez_jmp.pdf; Yujie Sude, Corey A. DeAngelis, and Patrick J. Wolf, “Supplying Choice: An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Voucher Programs in Washington, DC, Indiana, and Louisiana,” Journal of School Choice 12, no. 1 (2018): 8–33.

Specialization

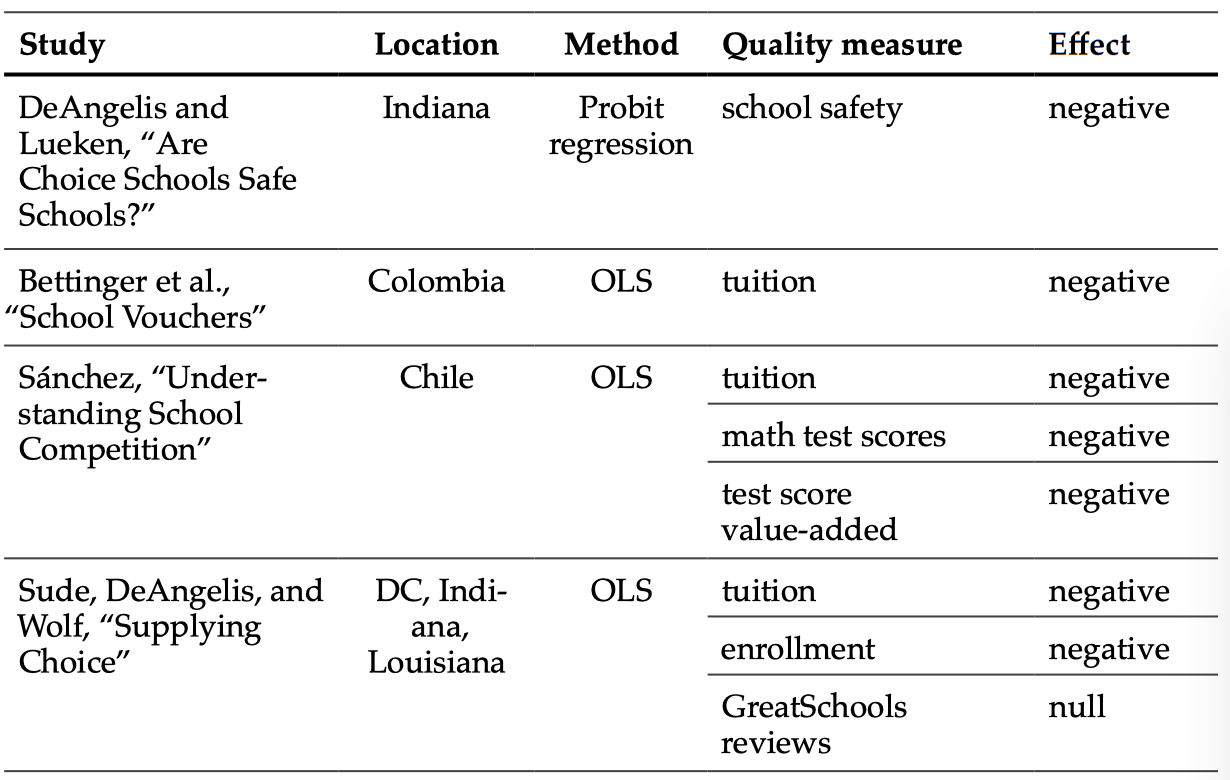

As Michael McShane, director of national research at EdChoice, theorized, “overregulation can have a chilling effect on diversity and innovation.”45Michael Q. McShane, Rethinking Regulation: Overseeing Performance in a Diversifying Educational Ecosystem (Indianapolis: EdChoice, May 2018). Regulations might lead to homogenization in the private school market for a couple of reasons.46Lindsey M. Burke, “Avoiding the ‘‘Inexorable Push toward Homogenization’ in School Choice: Education Savings Accounts as Hedges against Institutional Isomorphism,” Journal of School Choice 10, no. 4 (2016): 560–78. First, because program regulations largely mirror regulations in traditional public schools, the switching costs associated with program participation will be higher for the most specialized private schools. Private schools that already operate similarly to traditional public schools, on the other hand, will tend to face lower switching costs associated with program requirements. Second, some of the regulations associated with program participation make it particularly difficult for private schools to remain specialized. For example, the Louisiana voucher program requires that participating private schools use random admissions processes, which could make it challenging for schools to maintain high academic standards or specialized missions.47“Louisiana Scholarship Program,” EdChoice, accessed May 19, 2020, https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/louisiana-scholarship-program/. Private schools participating in the LSP must also administer the state’s standardized tests, which could increase the costs associated with deviating from the government’s uniform curriculum. Private schools participating in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program must use random admissions processes and must allow students to opt out of religious programs.48“Wisconsin—Milwaukee Parental Choice Program,” EdChoice, accessed May 19, 2020, https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/wisconsin-milwaukee-parental-choice-program/.

Again, most of the evidence on the subject of specialization is merely correlational. However, just about all the correlational evidence indicates that more-specialized schools tend to be less likely to participate in voucher programs (see table 5). Four descriptive studies find that a significant share of private school leaders report that they are concerned about school choice programs’ effects on their schools’ specialized identities.49Austin, “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy”; Megan J. Austin, “Organizational and Social Costs of Schools’ Participation in a Voucher Program,” in School Choice at the Crossroads: Research Perspectives, ed. Mark Berends, R. Joseph Waddington, and John Schoenig (New York: Routledge, 2019); Egalite et al., School Leaders’ Voices; Kisida, Wolf, and Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools. One 2015 study finds that 55 percent of private school leaders in Louisiana, 63 percent in Indiana, and 39 percent in Florida were concerned about school choice programs having an effect on their “independence, character, or identity.”50Kisida, Wolf, and Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools. Megan Austin has found that “schools choosing to participate in the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program were most concerned with how their academic and religious identity would be affected.”51Austin, “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy.” She interviewed principals of 10 Catholic schools that had chosen to participate in the program and finds additional costs associated with adapting to the needs of new students while maintaining school identity.52Austin, “Organizational and Social Costs.” The authors of a 2018 study find that 14 to 18 percent of private school leaders in North Carolina reported concerns about the voucher program’s effects on their school’s identity.53Egalite et al., School Leaders’ Voices.

A 2019 study finds that private schools identifying as “regular schools” are more likely than nonregular schools to participate in school choice programs in Indiana, Louisiana, North Carolina, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Washington, DC.54Corey A. DeAngelis, “Which Schools Participate? An Analysis of Private School Voucher Program Participation Decisions across Seven Locations” (working paper, 2019), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3309754. Overall, schools that identify as primarily serving students with special needs, schools that focus on early childhood education, and alternative schools are less likely to participate in voucher programs than schools that identify as regular. Private schools that focus on supporting homeschooled students are less likely to participate than those that do not, and non-coeducational schools are less likely to participate than coeducational schools. Two studies have found that individual private schools in Indiana, Florida, Louisiana, Ohio, and Washington, DC, tend to be less likely to identify as specialized or alternative—and more likely to identify as regular—when they switch into voucher program environments.55Corey A. DeAngelis and Lindsey M. Burke, “Does Regulation Induce Homogenisation? An Analysis of Three Voucher Programmes in the United States,” Educational Research and Evaluation 23, no. 7–8 (2017): 311–27; Corey A. DeAngelis and Lindsey M. Burke, “Does Regulation Reduce Specialization? Examining the Impact of Regulations on Private Schools of Choice in Five Locations” (Working Paper 2019-1, EdChoice, March 14, 2019). A 2019 study finds that individual private schools in Indiana, Louisiana, and Washington, DC, are around two percentage points less likely to report that they focus on supporting homeschooling after they switch into voucher program environments.56Corey A. DeAngelis and Angela K. Dills, “Is School Choice a Trojan Horse? The Effects of School Choice Laws on Homeschool Prevalence,” Peabody Journal of Education 94, no. 3 (2019): 342–54.

Two survey experiments address this question. One finds that the random admissions mandate has around a 25 percentage point negative effect on expected participation for nonregular (specialized) private schools and around a 17 percentage point negative effect on expected participation for regular (nonspecialized) private schools.57DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: California and New York.” However, while the difference of around 8 percentage points suggests that the random admissions regulation is more costly for specialized private schools, it is not statistically significant. The second study similarly finds that the negative effects of school choice regulations on expected program participation do not differ by private school specialization.58DeAngelis, Burke, and Wolf, “Effects of Regulations: Florida.”

Table 5. Effect of School Choice Regulations on Specialization of Participating Private Schools

a While Egalite et al. find that 14 to 18 percent of private school leaders in North Carolina report that the voucher program’s effects on their school’s identity is a concern, 82 to 86 percent indicate that this is not a concern.

Note: RCT = randomized controlled trial, OLS = ordinary least squares regression. “Negative” indicates that the study found a statistically significant negative relationship between program regulations and the specialization of the participating private schools. “Null” indicates that the study found no relationship between program regulations and the specialization of the participating private schools. Null to negative indicates that the study found null to negative relationships between program regulations and the specialization of the participating private schools.

Sources: Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from California and New York” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-07, University of Arkansas, Department of Education Reform, 2019); Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from Florida,” Social Science Quarterly 100, no. 6 (2019): 2316–36; Corey A. DeAngelis and Lindsey M. Burke, “Does Regulation Reduce Specialization? Examining the Impact of Regulations on Private Schools of Choice in Five Locations” (Working Paper 2019-1, EdChoice, March 14, 2019); Corey A. DeAngelis and Lindsey M. Burke, “Does Regulation Induce Homogenisation? An Analysis of Three Voucher Programmes in the United States,” Educational Research and Evaluation 23, no. 7–8 (2017): 311–27; Corey A. DeAngelis and Angela K. Dills, “Is School Choice a Trojan Horse? The Effects of School Choice Laws on Homeschool Prevalence,” Peabody Journal of Education 94, no. 3 (2019): 342–54; Corey A. DeAngelis, “Which Schools Participate? An Analysis of Private School Voucher Program Participation Decisions across Seven Locations” (working paper, 2019), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3309754; Megan J. Austin, “Organizational and Social Costs of Schools’ Participation in a Voucher Program,” in School Choice at the Crossroads: Research Perspectives, ed. Mark Berends, R. Joseph Waddington, and John Schoenig (New York: Routledge, 2019); Megan J. Austin, “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy: Participation Decisions and Early Implementation Experiences in the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program,” Journal of School Choice 9, no. 3 (2015): 354–79; Anna J. Egalite et al., School Leaders’ Voices: Private School Leaders’ Perspectives on the North Carolina Opportunity Scholarship Program, 2018 Update, OS Evaluation Report #6 (NC State College of Education, October 2018); Brian Kisida, Patrick J. Wolf, and Evan Rhinesmith, Views from Private Schools: Attitudes about School Choice Programs in Three States (American Enterprise Institute, January 2015).

Conclusion and Policy Implications

If a family is unhappy with the education services provided by their residentially assigned public school, they generally only have four options: (1) pay for a private school out of pocket while still paying for the public school through property taxes, (2) incur the costs associated with homeschooling while still paying for the public school through property taxes, (3) move to a different residence that is assigned to a better public school, or (4) tell the residentially assigned public school to change and hope that things get better soon. Because each of these options is highly costly for families—especially for low-income households—either in terms of actual financial costs or of time lost while waiting for the public school to change, economists would argue that residentially assigned public schools hold significant monopoly power in the education market.59Milton Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education,” in Economics and the Public Interest, ed. Robert A. Solo (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1955). In fact, the costs of these options are so high that parents have even gone to jail for trying to get their children into better public schools by lying about their residencies.60Erika Sanzi, “While Rich People Bribe Their Kids’ Way into College, Parents of Color Sit in Jail for Wanting Better Schools,” Education Post, March 13, 2019.

Private school choice programs decrease the costs associated with the first option by allowing families to use a fraction of their public education dollars to send their children to private schools. In theory, private school choice is expected to improve student outcomes by introducing competitive pressures into the market for education and putting power into the hands of consumers.61John E. Chubb and Terry M. Moe, “Politics, Markets, and the Organization of Schools,” American Political Science Review 82, no. 4 (1988): 1065–87; Corey A. DeAngelis, “Is Public Schooling a Public Good? An Analysis of Schooling Externalities” (Policy Analysis No. 842, Cato Institute, May 9, 2018); Caroline M. Hoxby, ed., The Economics of School Choice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). Families want their children to receive great educations, and parents are better positioned to understand their children’s education needs than distant bureaucrats. Public and private schools must cater to the needs of families if they wish to keep their doors open when families can vote with their feet. Private school choice programs might also lead to better education outcomes by improving matches between schools and students.62DeAngelis and Holmes Erickson, “What Leads to Successful School Choice Programs? A Review of the Theories and Evidence,” Cato Journal 38, no. 1 (2018): 247–63.

This review of the academic literature examines the impact of regulations on the quantity, quality, and specialization of private schools that decide to participate in school choice programs. On balance, the literature suggests that regulations are a net negative for school choice program design. Seven studies consider the relationship between regulations and private school participation in a school choice program, and all seven find negative effects, suggesting that onerous regulations reduce the likelihood of school participation. Eight studies look at the relationship between regulations and school quality; seven find that regulations could reduce the quality of the private schools that participate in school choice programs, and one finds null effects. Finally, ten studies examine the relationship between regulations and school specialization; seven studies suggest negative effects and three find null effects.

These findings also offer some possible explanations for the LSP’s persistent and large negative effects on math test scores. First, private schools might have a comparative advantage at shaping character skills that are not easily captured by standardized test scores. In other words, standardized math and reading test scores may not be strong proxies for students’ long-term success.63DeAngelis, “Divergences”; Hitt, McShane, and Wolf, “Do impacts on test scores”. Public schools have stronger incentives to teach to the test—and more experience with test taking—than private schools, meaning private school choice programs could decrease performance on standardized tests without actually negatively affecting learning in the short run.

However, it is also possible that students participating in the LSP are learning less than children in public schools. Because this is possible, we should be especially concerned about how the design of school choice programs could influence their effectiveness. The empirical evidence on the topic tends to suggest that regulations unintentionally decrease the quantity, quality, and specialization of private schools that elect to participate in choice programs. Of course, this doesn’t mean that policymakers should get rid of all school choice program regulations; instead, they need to more carefully weigh the intended benefits of regulations against the unintended—but realized—costs of regulations.

The most rigorous evidence suggests that while the open-admissions mandate aims to achieve equality, it has the largest negative effects on private school participation. The unintended result of the open- admissions mandate is the exact opposite of its intended effect. The regulation actually leads to less equality because fewer private schools participate, meaning that the least advantaged groups of students will have virtually no chance of attending those schools, while children from high-income families are still able to attend without financial assistance. Two survey experiments find that the state testing mandate significantly reduces the number of private schools available to students, whereas the nationally norm-referenced testing mandate is not associated with any significant reduction in options. In other words, if a testing regulation is necessary for the appearance of accountability to the public, policymakers should choose nationally norm-referenced tests to avoid the demonstrated unintended consequences of mandating the state test. The negative effects of state testing mandates are especially important to consider since research consistently finds that families do not strongly value standardized testing when they choose schools.64Jason Bedrick and Lindsey M. Burke, Surveying Florida Scholarship Families: Experiences and Satisfaction with Florida’s Tax-Credit Scholarship Program (Indianapolis: EdChoice, October 2018).

The evaluation of the LSP was the first experiment in the world to find statistically significant negative effects of a private school voucher program on student test scores. The negative effects were large. The LSP also has the two most intrusive program regulations—the random-admissions mandate and the requirement that private schools administer the state standardized tests. The LSP also mandates that private schools accept the voucher amount as full payment, which keeps the most expensive private schools from participating in the program. Only a third of the private schools in Louisiana elect to participate in the LSP, whereas over twice that proportion tend to participate in less-regulated programs. In addition, schools with declining enrollment and lower tuitions—proxies for school quality—are more likely to participate in the LSP, perhaps because they most need additional voucher funding.

Policymakers should consider the real costs associated with well-meaning regulations. The empirical evidence tends to suggest that regulations reduce the quantity, quality, and specialization of the private schools that participate in school choice programs. Policymakers could increase the number of meaningful options available to families by reducing top-down regulations of private school choice programs. Giving families real options—by avoiding onerous regulations—could increase the chances of success for the children that are most in need of better education options. If regulations reduce the variety and quality of private schools that choose to participate in school choice programs, they cut against the primary purpose of education choice: to provide more families with more options when it comes to their children’s education.

Much more research is needed on the impact of regulations on the supply and quality of private schools choosing to participate or not participate in a private school choice program. And policymakers and government officials will need to pay particular attention to the design of school choice programs and the regulations that govern them as education becomes more piecemeal and customized in the years to come. New modes of K–12 education delivery are unfolding every year, from new approaches to education financing with education savings accounts to changes in delivery through micro-schooling, online learning, private tutoring, and homeschooling co-ops, among other options. How the public and governments conceive of accountability, and how they understand the impact of specific regulations on these options, will shape the education landscape for decades.

References

Abdulkadiroğlu, Pathak, and Walters, “Free to Choose.”

Austin, Megan J. “Organizational and Social Costs of Schools’ Participation in a Voucher Program.” in School Choice at the Crossroads: Research Perspectives. Ed. Mark Berends, R. Joseph Waddington, and John Schoenig (New York: Routledge. 2019).

Austin, Megan J. “Schools’ Responses to Voucher Policy: Participation Decisions and Early Implementation Experiences in the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program.” Journal of School Choice 9. No. 3 (2015): 354–79.

Barnard, John et al. “Principal Stratification Approach to Broken Randomized Experiments: A Case Study of School Choice Vouchers in New York City.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 98. No. 462 (2003): 299–323.

Bedrick, Jason and Lindsey M. Burke. Surveying Florida Scholarship Families: Experiences and Satisfaction with Florida’s Tax-Credit Scholarship Program (Indianapolis: EdChoice. October 2018).

Bedrick, Jason. “Leave School Choice to the States.” TownHall.com. April 16, 2015.

Bedrick, Jason. “The Folly of Overregulating School Choice.” Education Next. January 5, 2016.

Bettinger, Eric et al. “School Vouchers, Labor Markets and Vocational Education” (Borradores de Economía No. 1087. Banco de la República. Colombia, 2019).

Burke, Lindsey M. “Avoiding the ‘‘Inexorable Push toward Homogenization’ in School Choice: Education Savings Accounts as Hedges against Institutional Isomorphism.” Journal of School Choice 10. No. 4 (2016): 560–78.

Chingos, Matthew M. et al. “The Effects of Means-Tested Private School Choice Programs on College Enrollment and Graduation” (Research Report. Urban Institute. Washington, DC. July 2019).

Chubb, John E. and Terry M. Moe. “Politics, Markets, and the Organization of Schools.” American Political Science Review 82. No. 4 (1988): 1065–87.

Cowen, Joshua M. “School Choice as a Latent Variable: Estimating the ‘Complier Average Causal Effect’ of Vouchers in Charlotte.” Policy Studies Journal 36. No. 2 (2008): 301–15.

DeAngelis, Corey A. and Holmes Erickson. “What Leads to Successful School Choice Programs? A Review of the Theories and Evidence.” Cato Journal 38. No. 1 (2018): 247–63.

DeAngelis, Corey A. “Divergences between Effects on Test Scores and Effects on Non-cognitive Skills.” Educational Review 2019.

DeAngelis, Corey A. “Do Self-Interested Schooling Selections Improve Society? A Review of the Evidence.” Journal of School Choice 11. No. 4 (2017): 546–58.

DeAngelis, Corey A. “Is Public Schooling a Public Good? An Analysis of Schooling Externalities” (Policy Analysis No. 842. Cato Institute. May 9, 2018).

DeAngelis, Corey A. “Regulatory Compliance Costs and Private School Participation in Voucher Programs.” Journal of School Choice 14. No. 1 (2020): 95–121.

DeAngelis, Corey A. “Which Schools Participate? An Analysis of Private School Voucher Program Participation Decisions across Seven Locations” (Working paper. 2019). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3309754.

DeAngelis, Corey A. and Angela K. Dills. “Is School Choice a Trojan Horse? The Effects of School Choice Laws on Homeschool Prevalence.” Peabody Journal of Education 94. No. 3 (2019): 342–54.

DeAngelis, Corey A. and Blake Hoarty. “Who Participates? An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Two Voucher Programs in the United States” (Policy Analysis No. 848. Cato Institute. 2018).

DeAngelis, Corey A. and Lindsey M. Burke. “Does Regulation Induce Homogenisation? An Analysis of Three Voucher Programmes in the United States.” Educational Research and Evaluation 23. No. 7–8 (2017): 311–27.

DeAngelis, Corey A. and Lindsey M. Burke. “Does Regulation Reduce Specialization? Examining the Impact of Regulations on Private Schools of Choice in Five Locations” (Working Paper 2019-1. EdChoice. March 14, 2019).

DeAngelis, Corey A. and Martin F. Lueken. “Are Choice Schools Safe Schools? A Cross-Sector Analysis of K–12 Safety Policies and School Climates in Indiana” (Working Paper 2019-2. EdChoice. April 3, 2019).

DeAngelis, Corey A., Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf. “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from California and New York” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-07. University of Arkansas. Department of Education Reform. 2019).

DeAngelis, Corey A., Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf. “The Effects of Regulations on Private School Choice Program Participation: Experimental Evidence from Florida.” Social Science Quarterly 100. No. 6 (2019). 2316–36.

EdChoice. The ABCs of School Choice: The Comprehensive Guide to Every Private School Choice Program in America. 2020 ed.

Egalite, Anna J. “Measuring Competitive Effects from School Voucher Programs: A Systematic Review.” Journal of School Choice 7. No. 4 (2013): 443–64.

Egalite, Anna J. et al. School Leaders’ Voices: Private School Leaders’ Perspectives on the North Carolina Opportunity Scholarship Program, 2018 Update. OS Evaluation Report #6 (NC State College of Education. October 2018).

Figlio, David and Krzysztof Karbownik. Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, Competition, and Performance Effects (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute. 2016).

Foreman, Leesa M. “Educational Attainment Effects of Public and Private School Choice.” Journal of School Choice 11. No. 4 (2017): 642–54.

Friedman, Milton. “The Role of Government in Education.” in Economics and the Public Interest. Ed. Robert A. Solo (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. 1955).

Greene, Jay P. “The Effect of School Choice: An Evaluation of the Charlotte Children’s Scholarship Fund Program.” Civic Report 12 (2000): 1–15.

Greene, Jay P., Paul E. Peterson, and Jiangtao Du. “Effectiveness of School Choice: The Milwaukee Experiment.” Education and Urban Society 31. No. 2 (1999): 190–213.

Harris, Douglas. “The Reform Debate, Part II: The Difference between Charter and Voucher Schools.” Education Week. November 11, 2015.

Hess, Frederick M. “Does School Choice ‘Work’?” National Affairs 5. No. 1 (Fall 2010): 35–53.

Hitt, McShane, and Wolf. “Do impacts on test scores even matter? Lessons from long-run outcomes in school choice research” (American Enterprise Institute. 2018).

Howell, William G. et al. “School Vouchers and Academic Performance: Results from Three Randomized Field Trials.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21. No. 2 (2002): 191–217.

Hoxby, Caroline M. ed. The Economics of School Choice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2007).

Jin, Hui, John Barnard, and Donald B. Rubin. “A Modified General Location Model for Noncompliance with Missing Data: Revisiting the New York City School Choice Scholarship Program Using Principal Stratification.” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 35. No. 2 (2010): 154–73.

Kisida, Brian, Patrick J. Wolf, and Evan Rhinesmith. Views from Private Schools: Attitudes about School Choice Programs in Three States (American Enterprise Institute. January 2015).

Lee, Matthew H., Jonathan N. Mills, and Patrick J. Wolf. “Heterogeneous Impacts across Schools in the First Four Years of the Louisiana Scholarship Program” (EDRE Working Paper 2019-11. University of Arkansas. Department of Education Reform. Fayetteville, AR. April 23, 2019).

“Louisiana Scholarship Program.” EdChoice. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/louisiana-scholarship-program/.

Machan, Tibor R. “Government Regulation of Business: The Moral Arguments.” Foundation for Economic Education. July 1, 1988.

McShane, Michael Q. ed. New and Better Schools: The Supply Side of School Choice (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. 2015).

McShane, Michael Q. Rethinking Regulation: Overseeing Performance in a Diversifying Educational Ecosystem (Indianapolis: EdChoice. May 2018).

Mills, Jonathan N. “The Effectiveness of Cash Transfers as a Policy Instrument in K-16 Education” (University of Arkansas Theses and Dissertations. 2015).

Mills, Jonathan N. and Patrick J. Wolf. “The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement after Four Years” (EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-10. University of Arkansas. Department of Education Reform. 2019).

Mills, Jonathan N. and Patrick J. Wolf. “Vouchers in the Bayou: The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement after 2 Years.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 39. No. 3 (2017): 464–84.

Rouse, Cecilia Elena. “Private School Vouchers and Student Achievement: An Evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113. No. 2 (1998): 553–602.

Samuelson, Paul A. “Consumption Theory in Terms of Revealed Preference.” Economica 15. No. 60 (1948): 243–53.

Sánchez, Cristián. “Understanding School Competition under Voucher Regimes” (Working paper. September 17, 2018). http://econweb.umd.edu/~sanchez/files/csanchez_jmp.pdf.

Sanzi, Erika. “While Rich People Bribe Their Kids’ Way into College, Parents of Color Sit in Jail for Wanting Better Schools.” Education Post. March 13, 2019.

Stuit, David and Sy Doan. School Choice Regulations: Red Tape or Red Herring? (Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute. 2013).

Sude, Yujie, Corey A. DeAngelis, and Patrick J. Wolf. “Supplying Choice: An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Voucher Programs in Washington, DC, Indiana, and Louisiana.” Journal of School Choice 12. No. 1 (2018): 8–33.

Swanson, Elise. “Can We Have It All? A Review of the Impacts of School Choice on Racial Integration.” Journal of School Choice 11. No. 4 (2017): 507–26.

Waddington, R. Joseph and Mark Berends. “Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement Effects for Students in Upper Elementary and Middle School.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37. No. 4 (2018): 783–808.

Webber, Ann et al. Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts Three Years after Students Applied. NCEE 2019-4006 (National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. US Department of Education. 2019).

“Wisconsin—Milwaukee Parental Choice Program.” EdChoice. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/wisconsin-milwaukee-parental-choice-program/.

Wolf, Patrick J. “Civics Exam: Schools of Choice Boost Civic Values.” Education Next 7. No. 3 (2007): 66–73.

Wolf, Patrick J. et al. “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32. No. 2 (2013): 246–70.

Wolf, Patrick J. et al. Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Final Report. NCEE 2010-4018 (National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. US Department of Education. 2010).

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy