Every city in the United States has implemented land use regulations that limit the amount of housing that can be built within city borders and raise the cost of new housing construction. These rules are framed as tools for reducing the negative externalities of development, such as noise that carries across property lines or shadows that buildings cast on their neighbors. However, these regulations also stand in the way of people’s opportunity to live in the locality of their choice at a price affordable to their household. This chapter covers the history of land use regulations; the potential that a lightly regulated market could deliver housing at a wide range of price points; the effect of land use regulations on housing affordability; and, finally, potential solutions that could allow more people to live in the locations of their choice.

Localities implemented the early U.S. zoning codes during the Progressive Era. The first U.S. zoning code adopted in New York City in 1916 took steps toward limiting the mass of buildings as well as separating buildings by use. It was implemented at the behest of department store owners, who wanted to keep garment factories from encroaching on the blocks that they wanted to maintain as exclusive shopping destinations. Today, however, land use regulations primarily serve to separate single-family neighborhoods from land available for any other use and to prevent the redevelopment of a single-family home for any other use.

In addition to business interests, early supporters of zoning included progressive reformers. The reformers argued that tall buildings, made feasible by elevators and new construction techniques, contributed to disease by allowing high population density. With the advent of streetcar technology that made it possible for people to commute farther to their downtown jobs, these reformers supported clearing away densely populated, low-income neighborhoods and encouraging the residents to move to low-density, single-family homes with yards. Slum clearance was paired with the construction of public housing, but often there was a net loss of housing units and the public housing units were available to families with higher incomes than those who had been living in the bulldozed homes.1Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf, 1974), 1024.

When New York implemented its zoning code, other US cities were already working on their own land use ordinances that shared similar objectives of separating uses and limiting density.2 Raphael Fischler, “Health, Safety, and the General Welfare: Markets, Politics, and Social Science in Early Land-Use Regulation and Community Design,” Journal of Urban History 24, no. 6 (September 1998): 675–719.

Early zoning ordinances were not without their critics, primarily in the real estate industry. Some argued that land use regulations that reduced land values constitute an unconstitutional taking of private property and that localities lacked a rational basis for determining zoning designations. This theory was eventually put to the test in Euclid, Ohio. The Ambler Realty Company sued for the right to build an industrial project on land that was zoned for various other uses. In 1926, the case reached the US Supreme Court, and the court held that localities may legally separate land zoned for commercial and residential uses and multifamily from single-family zoned land.4Euclid v. Ambler, 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

From the beginning, land use regulation in the US has been a tool of exclusion. The New York shopkeepers who supported zoning to keep factories out of shopping districts were often more concerned about keeping the factories’ immigrant workers away from their stores than about the factories themselves.5Seymour Toll, Zoned American (New York: Grossman, 1969), 158-9. Until Buchanan v. Warley in 1916, some municipalities implemented pre-zoning land use regulations that explicitly barred African Americans from purchasing homes in parts of localities.6Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917). See also “Buchanan v. Warley,” Oyez, accessed May 5, 2020, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/245us60. Following the ruling that explicitly race-based zoning violated Fourteenth Amendment protections for freedom of contract, localities turned to zoning rules that drove up housing costs, including single-family zoning and minimum lot size requirements.7Though the Supreme Court overturned explicitly race-based zoning in 1916, local, state, and federal policy continued segregation in real estate for decades after. In 1934, in response to a housing shortage, the Federal Housing Authority was established to subsidize homebuying by insuring mortgages. However, the agency refused to insure homes in neighborhoods where black Americans lived. For a history of government-imposed segregation in housing, see Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017). While these rules segregate neighborhoods by income rather than race, they have outsize effects on racial groups, including African Americans (who have lower incomes on average than the average for the country as a whole).

As legal scholar Bernard Siegan explains,

All zoning is exclusionary, and is expected to be exclusionary; that is its purpose and intent. The provisions governing almost every zoning district operate to exclude certain uses of property from certain portions of the land, and thereby in the case of housing, the people who would occupy the housing excluded.8Bernard Siegan, Land Use without Zoning (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1972), 88. See also Fischler, “Health, Safety, and the General Welfare.”

When jurisdiction after jurisdiction implements exclusionary zoning, entire regions become unaffordable to low- and even middle-income households. Residents in search of affordable housing may move to exurbs that are far from many jobs and require long commutes, but at a certain point driving farther in search of affordability becomes untenable in terms of time and transportation costs.

Some early zoning proponents said that reducing population density would improve public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo made a similar argument, tweeting of New York City, “Density is still too high and is still too dangerous.” However, in both instances, overcrowding was the threat to public health rather than density. Crowding refers to the number of people sharing a room, whereas density refers to the number of people living on a fixed amount of land. Overcrowding can occur in high- or low-density locations and has contributed to the spread of Covid-19 from urban to rural low-income areas. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have identified no correlation between either population density or crowding and Covid-19 infection rates at the county level.9Shima Hamidi, Sadegh Sabouri, and Reid Ewing, “Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic?” Journal of the American Planning Association 86, no. 4 (June 2020), 495-509. However, other analyses have found a relationship between crowding and Covid-19 spread.10Ian Lovett, Dan Frosch, and Paul Overberg, “Covid-19 Stalks Large Families in Rural America,” The Wall Street Journal, June 7, 2020. To the extent that reduced crowding improves public health, permitting more housing to be built at lower costs in the locations where people want to live supports not only economic opportunity, but better health outcomes as well.

Filtering: How the Market Can Deliver Housing Affordability

Through the mid-20th century, housing markets provided housing to residents at a wide range of income levels, even in the face of rapid population growth. In his book Living Downtown, Paul Groth explains that boarding houses and single-room-occupancy buildings provided a key source of market-rate housing that was affordable even to very low-wage workers in cities like San Francisco and New York.11“Appendix: Hotel and Employment Statistics” in Paul Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994). By sharing a bathroom and relying on urban neighborhoods to provide affordable food options and space for socializing, these residents were able to keep their living costs affordable even in cities with high land prices. Today, land-use restrictions that require each new housing unit to be a minimum size and include prescribed amenities rule out lower-cost housing options.

Before zoning was implemented in Manhattan, neighborhoods that had been built as single-family homes were often repurposed as boarding houses to put real estate to its most profitable use in a rapidly growing city. While historically land use regulations allowed builders to provide housing that was designed for low-income tenants, housing that had been initially built for high- or middle-income residents also tended to become more affordable to less-well-off residents over time. Because lower-income residents were willing to share space in subdivided houses or purpose-built apartments, they were able to outbid higher-income residents for the most desirable locations.12Charles Lockwood, Manhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976; repr., Dover, 2014), 293. Those who wanted to live in a single-family home surrounded by other single-family homes had to keep moving northward as land in the heart of the city was put to more valuable use over time as denser housing and commercial space.13Lockwood, Manhattan Moves Uptown.

In liberal markets, housing becomes affordable to lower-income people over time in two ways. First, a household may sell a house to a landlord, who then rents it out as rooms or converts it into an apartment building. This process turns one large home into smaller, more affordable homes. But second, even housing that isn’t subdivided becomes more affordable over time through a process called filtering. The majority of people moving into new-construction housing are moving out of older, somewhat less desirable housing. Today, land use regulations that limit new housing construction and set minimum standards for housing unit sizes have restricted both the rate of filtering and the price point it can start from. Nonetheless, filtering provides an important source of housing affordable to low- and middle-income Americans today. According to one estimate, filtering leads real home prices to fall by 1.9 percent per year.14Stuart Rosenthal, “Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a ‘Repeat Income’ Model,” American Economic Review 104, no. 2 (February 2014): 687–706.

Economist Evan Mast looks at the moves that new construction causes in a study of 686 multifamily developments.15Evan Mast. “The Effect of New Market-Rate Housing Construction on the Low-Income Housing Market,” (Upjohn Institute Working Paper 19-307, 2019). Mast finds that 100 new units open up 70 units in below-median income neighborhoods and 40 units in bottom-quintiles income neighborhoods.

The filtering process can start from a lower price point if localities allow for relatively low-cost new construction typologies, including multifamily construction. Additionally, the process accelerates when existing homes are allowed to be subdivided into smaller homes. Today, single-family zoning prevents such subdivision in the majority of the country’s residential neighborhoods. Neighborhoods and cities that have set up severe obstacles to new housing construction may experience the reverse of filtering, in which a stagnant supply of housing becomes more expensive over time as demand increases and existing homes go to higher-income residents over time.16Rosenthal, “Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing?” Rosenthal points out that house price inflation, which occurs when demand for housing increases in places with severe zoning constraints, can cause housing to “filter up.”

Increasingly Binding Housing Supply Constraints

Not all land use regulations change development outcomes. In some cases when land at the outskirts of urban regions is developed for the first time, localities zone the land to match what homebuilders want to provide. In this case, regulations may be non-binding. Rules that do have an effect on development outcomes are called binding regulations.

Land use regulations in US cities have become more binding over time, and as a result they’re having larger effects on housing supply and house prices.17Joseph Gyourko and Raven Molloy, “Regulation and Housing Supply,” in Gilles Duranton, J. Vernon Henderson, William C. Strange, eds., Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics Volume 5, (2015): 1291-2. Localities have been using zoning to limit development for more than 100 years, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that entire regions began experiencing high and rising house prices in response to these supply constraints.18William A. Fischel, “The Rise of the Homevoters: How OPEC and Earth Day Created Growth-Control Zoning That Derailed the Growth Machine” (working paper, Marron Institute, February 2016). Before that time period, center cities typically courted growth while built-out suburbs sought to limit it in order to maintain low density.19Harvey Molotch, “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place,” American Journal of Sociology 82, no. 2 (1976): 309–32. Nonetheless, farther-flung suburbs generally still had plenty of undeveloped land that they were willing to make available for relatively low-cost development.

Economist William Fischel argues that the rise of the environmental movement led to a sympathetic argument that homeowners could use in support of limiting development.20William A. Fischel, “An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for Its Exclusionary Effects,” Urban Studies 41, no. 2 (February 2004). Neighbors who oppose growth in their proximity may argue that development would harm local habitats. On a larger scale, however, infill growth—redeveloping existing neighborhoods at denser levels—is much less environmentally harmful than new growth at the urban fringe.21For a review of the evidence on the environmental effects of infill development versus new suburban development, see David Owen, Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less Are the Keys to Sustainability (New York: Penguin, 2009). Nonetheless, homeowners, whom Fischel labels “homevoters” for their outsize influence on local policy decisions, have used environmental concerns to successfully block development in many jurisdictions.22Fischel, “Economic History of Zoning.” By blocking change in their neighborhoods, homevoters may limit the risk that new construction could lower the value of their home, which is often their largest financial asset. They also create the potential for large windfall gains, should demand for housing increase in an area where building new supply is politically difficult.23Fischel, “Economic History of Zoning.”

The problem of inelastic housing supply—a housing market in which increases in demand for housing result in relatively little construction and relatively large prices increases—in a policy environment shaped by homevoters is most severe in high-cost coastal cities. But it’s not limited to these jurisdictions. During the housing boom from 2012 through 2017, house prices rose significantly faster than household incomes. Relative to the boom from 1996 to 2006, however, the housing supply response has been substantially smaller during the more recent boom.24Knut Are Aastveit, Bruno Albuquerque, and André Anundsen, “Time-Varying Housing Supply Elasticities and US Housing Cycles” (working paper, January 31, 2018), https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=IAAE2018&paper_id=397. Since the financial crisis, no metro area in the country has reached the rate of residential building permits per capita that it experienced from 1990 to 2007.25Sarah Holder, “The Cities Where Job Growth Is Outpacing New Homes,” CityLab, September 9, 2019.

The Land Use Regulations Preventing New Housing Construction

The most important land use regulation standing in the way of new housing is single-family zoning. In California, the state with the largest affordability problem, 80 percent of the land zoned for residential development is designated exclusively for single-family housing, and denser housing typologies are banned in these areas.26Kerry Cavanaugh, “Holy Cow! California May Get Rid of Single-Family Zoning,” Los Angeles Times, April 24, 2019.

On top of single-family zoning that restricts lower-cost multifamily housing construction, all US cities and suburbs enforce rules including minimum lot size requirements and setback requirements that require each home to sit on a certain amount of land. Using data from 2000, urban economists Edward Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks estimate the cost of regulations that limit residential construction. They find that New York; Boston; Los Angeles; Newport News, Virginia; Oakland, California; Salt Lake City; San Francisco; San Jose, California; and Washington, DC, all have “zoning taxes” that accounted for at least 10 percent of housing costs at the time of their study.27Edward L. Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks, “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in House Prices” (NBER Working Paper No. 10124, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, November 2003). Housing affordability and the effects of land use regulations on new housing supply have certainly become worse since 2000.

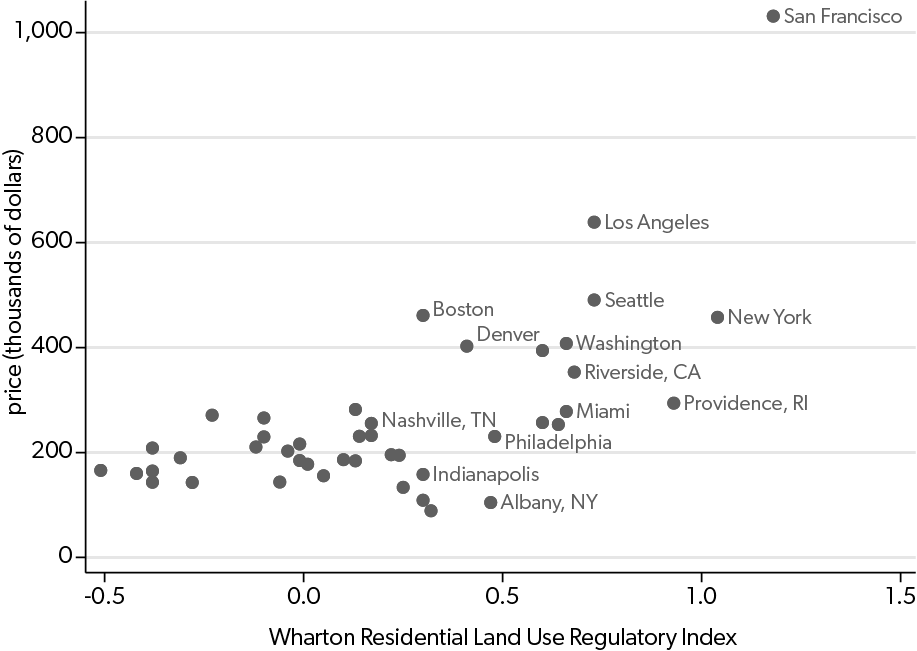

Gyourko and coauthors Jonathan Hartley and Jacob Krimmel recently released an index of land use regulations and building permit approval processes across metropolitan areas. To develop their Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index (WRLURI), they survey policymakers in jurisdictions across the country.28Joseph Gyourko, Jonathan Hartley, and Jacob Krimmel, “The Local Residential Land Use Regulatory Environment across U.S. Housing Markets: Evidence from a New Wharton Index” (NBER Working Paper No. 26573, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, December 2019). This paper updates the WRLURI, which was first published in Joseph Gyourko, Albert Saiz, and Anita Summers, “A New Measure of the Local Regulatory Environment for Housing Markets: The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index,” Urban Studies 45, no. 3 (March 2008): 693–729. Of course, many market and policy factors beyond zoning affect house prices, such as regional demand for housing and geographic constraints on building new housing, among others. Nonetheless, local rules and institutions that determine what can be built in a locality and how long developers typically have to spend to get approvals are an important factor in determining house prices. Figure 1 shows the relationship between WRLURI and median house prices. WRLURI explains 40 percent of price variation across metropolitan areas.

In high-cost cities, limits on density clearly prevent the subdivision and redevelopment that market actors would otherwise make to increase housing supply and bring down prices. But new research shows that these regulations shape market outcomes even in places with relatively elastic housing supply. Researchers Nolan Gray and Salim Furth show that in three fast-growing Texas suburbs, new homes are concentrated close to the minimum zoned lot size, indicating the presence of binding regulations.29Nolan Gray and Salim Furth, “Do Minimum-Lot-Size Regulations Limit Housing Supply in Texas?” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, November 2015). Additionally, many developers in these jurisdictions seek variances in order to build new homes on lots that are smaller than the minimum allowable lot size on the books.30Gray and Furth, “Do Minimum-Lot-Size Regulations Limit Housing Supply?” Seeking regulatory exemptions adds to the costs of development, and the additional cost is passed on to consumers in the form of higher house prices.

In addition to density restrictions, in jurisdictions where land is expensive, parking requirements play an important role in driving up housing construction costs. When land is scarce, developers build mandated parking in aboveground or underground garages where each spot costs tens of thousands of dollars to build. In one typical Los Angeles multifamily project, parking was only feasible to build in an underground garage. For each one-bedroom unit in Los Angeles, developers are required to build two parking spots, at a cost of more than $100,000 per unit.31Donald C. Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking (Chicago: American Planning Association, 2011), 90. In the absence of parking requirements, residential builders would still provide parking to people willing to pay for it, but households willing to forgo a car (or to have one car instead of two) would have the freedom to economize on parking costs.

On top of restrictions that limit density and housing supply within cities, in some cases additional land use restrictions limit new building at the urban fringe. Urban growth boundaries (UGBs) are a key component of smart growth planning, a planning school that emerged in the 1970s as a response to traditional zoning practices that restrict traditional development patterns.

However, smart growth principles have never been fully implemented. Rather than repealing rules like parking requirements and single-family zoning that stand in the way of dense, walkable development, local policymakers who have implemented smart growth policies have generally layered UGBs on top of these traditional zoning restrictions. In turn, UGBs have further constrained new housing supply and contributed to house price increases.

Figure 1. Median House Price and Land Use Restrictions across Metropolitan Areas, 2019

Sources: Index values are from Joseph Gyourko, Jonathan Hartley, and Jacob Krimmel, “The Local Residential Land Use Regulatory Environment across U.S. Housing Markets: Evidence from a New Wharton Index” (NBER Working Paper No. 26573, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, December 2019); median house price data are from “Housing Data,” Zillow Research, ZHVI All Homes Time Series ($) (data set), accessed February 24, 2020, https://www.zillow.com/research/data/.

Research is mixed on the effect of UGBs on house prices. Portland, Oregon, has perhaps the most binding UGB in the country. One study found that Portland’s UGB did not cause house prices around Portland to rise between 1990 and 2000.32Myung-Jin Jun, “The Effects of Portland’s Urban Growth Boundary on Housing Prices,” Journal of the American Planning Association 72, no. 2 (2006): 239–43. Since then, however, Portland house prices have more than doubled after accounting for inflation. Other studies have found that UGBs raise land prices for land inside the boundary,33Gerrit J. Knaap, “The Price Effects of Urban Growth Boundaries in Metropolitan Portland, Oregon,” Land Economics 61, no. 1 (1985): 26. and a study from the 1980s found the same effect for house prices.34Keith R. Ihlanfeldt, “The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices,” Journal of Urban Economics 61, no. 3 (2007): 420–35. Historic neighborhoods often have the characteristics that smart growth advocates promote, including dense, walkable development.

But traditional zoning and historic preservation rules prevent new development in these neighborhoods that would allow more people to live in them. Historic preservation is particularly prevalent in Manhattan, where nearly one-third of buildings are landmarked.35Ingrid Gould Ellen, Brian J. McCabe, and Eric Edward Stern, “Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in New York City” (Fact Brief, Furman Center at New York University, March 2016). One study of the effects of preservation on house prices finds that outside Manhattan in New York City, historic preservation increases property prices of homes that have redevelopment potential and those that are landmarked. However, within Manhattan, where the option to redevelop is most valuable, historic designation raises the prices of homes that are not preserved but has a smaller positive price effect for those that are.36Vicki Been et al., “Preserving History or Hindering Growth? The Heterogeneous Effects of Historic Districts on Local Housing Markets in New York City” (NBER Working Paper 20446, National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2014).

On the whole, there is a strong consensus among economists that in expensive coastal regions land use regulations are standing in the way of new housing construction and are causing high and rising house prices.37Joseph Gyourko and Raven Molloy, “Regulation and Housing Supply” (NBER Working Paper No. 20536, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, October 2014).

Consequences of Supply Constraints and High Prices for Housing

Land use regulations that constrain building supply and lead to an inelastic supply of housing harm society’s most vulnerable members the most. These regulations have devastating effects for low-income renters in high-cost cities. On average, households in the lowest income quintile spend more than 60 percent of their income on housing, whether they’re renters or homeowners.38Jenny Schuetz, “Cost, Crowding, or Commuting? Housing Stress on the Middle Class,” Brookings Institution, May 7, 2019. This means typical low-income households are severely cost-burdened: they may have insufficient funds to meet their other needs beyond housing, they may live in crowded conditions, or they may endure long and unpleasant commutes. A study from Zillow finds that as median rents exceed 32 percent of the median household’s income, homelessness rates begin to rise.39Chris Glynn and Alexander Casey, “Homelessness Rises Faster Where Rent Exceeds a Third of Income,” Zillow Research, December 11, 2018.

The consequences of land use regulations that constrain housing supply are not limited to residents who are directly burdened by high rents. Land use regulations also have macroeconomic consequences because they cause “spatial misallocation,” meaning workers don’t live in the locations with the best opportunities because of housing supply constraints.40Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics” 11, no. 2 (2019): 1-39. While the highest-earning individuals can afford housing in the location of their choice, land use regulations may force those earning less to choose between living in the location where their best job opportunities are located and living in a location where they can afford decent housing and a reasonable commute.

Land use regulations reduce income mobility by shutting out relatively low-income residents from locations with high-paying jobs. Economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag show that income convergence across states between 1990 and 2010 was less than half of the rate it was from 1880 to 1980, as people stopped moving from lower-income states to higher-income states.41Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag, “Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined?” Journal of Urban Economics 102 (2017).

In addition to reducing income mobility, spatial misallocation reduces economic growth when people can’t live in the locations where they could be most productive. Cities provide opportunities for a high density of people and firms to collocate and learn from each other. By locking out population growth, land use regulations stand in the way of growth and innovation. Macroeconomists have estimated that land use regulations reduce US GDP substantially, by between hundreds of billions42Kyle F. Herkenhoff, Lee E. Ohanian, and Edward C. Prescott, “Tarnishing the Golden and Empire States: Land-Use Restrictions and the U.S. Economic Slowdown,” Journal of Monetary Economics 93 (2018): 89–109; and trillions of dollars.43Hsieh and Moretti, “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.”

Failed Solutions

In the face of high and rising housing costs in expensive cities, state and local policymakers are under pressure to pursue policies to increase affordability for their residents. In 2019, Oregon and California passed statewide rent control laws in an attempt to reduce rent burdens and rent hikes for current tenants, and New York reformed its rent control policy to allow stricter rent control across the state.

Rent control gives tenants some of the benefits of homeownership by offering relatively predictable housing costs. However, it comes with serious consequences for the supply of rental housing. A recent study of rent control in San Francisco found that buildings affected by the city’s rent control law were 8 percentage points more likely to be converted to condos than buildings that were exempt from the law.44Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade, and Franklin Qian, “The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco” (NBER Working Paper No. 24181, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, January 2018). While rent control benefits those who live in rent-controlled units, the authors find that it reduced the supply of relatively low-cost rental housing, at the expense of renters who weren’t lucky enough to secure a protected apartment.

While rent control is primarily limited to some of the highest-cost coastal cities, inclusionary zoning is a similar policy becoming increasingly common across the country.45Brian Stromberg and Lisa Sturtevant, “What Makes Inclusionary Zoning Happen?” (Inclusionary Housing policy brief, National Housing Conference, May 2016). Under inclusionary zoning, homebuilders are required or incentivized to build below-market-rate housing units as part of new market-rate projects. The subsidized units are required to be affordable to households making a certain percentage of the median income over time. Localities often offer density bonuses that allow homebuilders to build more market-rate housing than they would be permitted to construct under the underlying zoning.

A requirement that developers provide subsidized housing as a component of new housing developments is a tax on new construction that can be expected to reduce housing supply and drive up prices. However, the density bonuses that inclusionary zoning often incorporates allow more housing supply than would otherwise be permitted. This makes its overall effect on new housing construction and market-rate house prices ambiguous.

Five studies have estimated the effect of inclusionary zoning on house prices, and three find that it increases prices relative to the counterfactual. One finds mixed effects, and one finds that inclusionary zoning reduced median market-rate prices.46For a review of the studies that estimate the effects of inclusionary zoning on new housing construction and market-rate house prices, see Emily Hamilton, “Inclusionary Zoning and Housing Market Outcomes” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington VA, September 2019). Further, the density bonuses that inclusionary programs typically include derive their value from the fact that traditional zoning regulations prevent homebuilders from providing as much housing as would be profitable given demand. Without exclusionary zoning that gives value to density bonuses, inclusionary zoning would be a clear tax on new housing construction.

Like rent control, inclusionary zoning can provide large benefits for the residents who receive price-controlled homes. Like rent control, it fails to address the core cause of housing unaffordability in growing regions—exclusionary zoning and limitations on relatively low-cost housing typologies. These policies give state and local politicians the tools to appear to address the problem of unaffordability without threatening the exclusionary zoning order that homevoters support.

Successful Reform at the Local Level

The homevoter dynamics at the local level create serious obstacles to reform at the local level. Relative to renters, homeowners are more likely to stay in the same jurisdiction over time,47Derrick Moore, “Overall Mover Rate Remains at an All-time Low,” U.S. Census Bureau, December 21, 2017. and they’re more likely to vote.48In 2016, 49% of renters voted, compared to 60% of homeowners. See Chris Salviati, “Renters vs. Homeowners at the Ballot Box—Will America’s Politicians Represent the Voice of Renters?,” Apartment List, October 30, 2018. Local politicians are therefore incentivized to appease these homevoters with exclusionary zoning policy rather than liberalizing housing policy to allow in new residents who might be less inclined to reelect them than the current electorate is.

Nonetheless, several US cities provide models for accommodating growth and maintaining affordability. Houston is famous for not having a zoning code and for allowing rapid suburban development on its urban fringe. But it also allows dense redevelopment. In 1999, Houston reduced the minimum lot size within its Interstate 610 loop to 1,400 square feet, making it possible for a single house to be redeveloped with three townhouses.49M. Nolan Gray and Adam A. Millsap, “Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis of the Causes and Effects of Houston’s 1998 Subdivision Reform,” Journal of Planning and Education Research (2020). More recently, it eliminated parking requirements in some downtown neighborhoods. Localities across the country, from Portland to Atlanta have legalized accessory dwelling units (ADUs). And Minneapolis implemented a zoning reform to permit triplexes across the parts of the city where previously only single-family houses were allowed. Rather than permitting a bit more density across the city, Seattle has taken the approach of permitting high-rise residential development in its “urban villages.”

These examples show that in some cases local reform is politically possible. However, local reform ends at the municipal limits, and metro areas comprise many jurisdictions, each of which sets its own land use regulations and is responsive to its own voters. In general, the incentives at the local level are biased in favor of the heavily regulated status quo.

Arguments in Support of Local Control in Land Use

In spite of the serious costs of allowing homevoters to have strong influence over land use regulations, local control over land use decisions remains popular among many groups. Historically, early progressive supporters of zoning and other land use regulations argued that these regulations were necessary for improving the living conditions of low-income people living in urban tenements. Conditions for low-wage workers in urban centers were indeed poor—homes were overcrowded, and crowding and poor sanitation contributed to public health problems.

As an alternative to urban apartments, progressives promoted moving the residents of tenements to suburbs, from which downtown jobs were newly accessible by streetcar. They argued that owner-occupied, single-family homes promoted healthy and virtuous lifestyles.50Kenneth Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 192. They promoted local land use regulations as a tool to maintain exclusively single-family development in the suburbs and to implement slum clearance policies to eliminate tenements in the cities.

Local control over land use regulations also has support among conservatives, who tend to prefer subsidiarity—the principle of devolving policy decisions to the lowest level of government possible. Political philosopher Loren King explains two justifications for this subsidiarity:

One rationale appeals to personal autonomy and liberal-democratic legitimacy: leave political decisions at the institutional scale closest to those affected by those judgments, just because legitimate authority rests—in the first and most critical instance—with the free and informed consent of those moral agents most obviously affected by political decisions. Political decisions are always ultimately backed by coercion, and such coercion can only be legitimately authorized by reasons that are responsive to each citizen’s equal moral standing as at once both the subject and the final author of that coercion. Decisions made closest to those most affected are more likely to satisfy this criterion of legitimacy, treating us as properly autonomous citizens. Another rationale is (moderately) communitarian in spirit. Our most cherished relationships tend to be in our families and communities, churches and neighborhoods—a variety of associations we are either born and raised into or sometimes choose to enter on the basis of our considered values and aspirations. It is typically within such communities that our broader conceptions of justice and the good life are formulated and affirmed. This associative richness is to be applauded, and if government must interfere with civic or nonpublic associations, best that it do so in ways that are least intrusive and most carefully tailored to achieve whatever public purposes necessitated interference in the first place.51Loren King, “Cities, Subsidiarity, and Federalism,” Nomos 55 (2014): 291–331.

In addition to both progressives and conservatives who offer ideological justifications for giving local governments control over land use, others support zoning from an efficiency perspective. They argue that bargaining over allowable land use is inefficient: A group of residents may be willing to pay a commercial landowner enough to entice the landowner to locate away from their neighborhood, but the residents face a coordination problem that keeps them from facilitating this transaction.52William A. Fischel, Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2015), 229–30. From this perspective, local governments stepping in to separate land uses is welfare-enhancing.

Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko write, “Empirical investigations of the local costs and benefits of restricting building generally conclude that the negative externalities are not nearly large enough to justify the costs of regulation.”53Edward L. Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko, “The Economic Implications of Housing Supply,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 32, no. 1 (Winter 2018): 3–30. Land use regulations do prevent externalities, for instance when they block tall buildings that would cast shadows on neighboring properties. However, they also prevent the positive externalities that emerge when more people are able to afford housing in their preferred location. In the abstract, most people agree that more housing should be permitted in the regions where people want to live. This is reflected in the plethora of proposals from federal policymakers for encouraging local zoning reform.54Michael Andersen, “It’s Official: DC Politicians Have Woken Up to Housing Abundance,” Sightline Institute, October 14, 2019. But when it comes to specific proposals for new housing, particularly multifamily housing, local residents very often find a reason to oppose construction in their backyard.

The Role for State Preemption

While a few localities have implemented pro-housing reforms, in general states have clear legal and economic bases for setting limits on local land use regulations. Local jurisdictions are “creatures of their states,” so even “home rule” states can limit local regulatory authority. The effects of local restrictions on new housing spill across local political boundaries, limiting population growth, economic growth, and income mobility at the state and national levels. Because reversing these trends are valid objectives for state policymakers, they have a role to play in limiting exclusionary zoning and protecting property owners’ rights to build more housing.

From its beginning, zoning has been used to block multifamily housing and uphold the authority of local governments to create exclusively single-family neighborhoods.55See, for example, Lionshead Lake, Inc. v. Township of Wayne, 10 N.J. 165, 89 A.2d 693 (1952). “People who move into the country rightly expect more land, more living room, indoors and out, and more freedom in their scale of living than is generally possible in the city. City standards of housing are not adaptable to suburban areas and especially to the upbringing of children. But quite apart from these considerations of public health which cannot be overlooked, minimum floor-area standards are justified on the ground that they promote the general welfare of the community.” This has arguably been more consequential than zoning’s role in separating incompatible land uses, particularly as industrial uses have become cleaner over time and as changes in transportation networks have naturally led industrial users to want to move away from dense urban areas.

In the Supreme Court, local governments’ police power to protect “general welfare” has been interpreted such that local policymakers may restrict property rights in land use to meet the preferences and financial interests of the jurisdiction’s current residents, with no consideration for the costs of these policies to property owners or to prospective residents who are shut out of the jurisdiction by supply constraints.56Euclid v. Ambler, 272 U.S. 365 (1926). But not all state courts share this jurisprudence. For example, New Jersey courts have held that municipalities must consider the effects of their zoning laws on residents who live outside their borders.57Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Township of Mount Laurel, 67 N.J. 151, 336 A.2d 713 (1975). For a history of the Mount Laurel decision, see David L. Kirp, John P. Dwyer, and Larry A. Rosenthal, Our Town: Race, Housing, and the History of Suburbia (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997).

Recent reforms at the state level show how states may set limits on local exclusionary zoning. In 2019, Oregon passed a state law that eliminated single-family zoning in much of the state. It requires all localities with at least 25,000 residents to allow up to fourplexes or “cottage clusters” of small single-family homes on lots currently zoned for single-family units exclusively.58H.B. 2001, 80th Leg. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Oregon 2019). See also “2019 Session: House Bill 2001,” Your Government website (OregonLive.com), accessed May 5, 2020, https://gov.oregonlive.com/bill/2019/hb2001/. For cities with between 10,000 and 25,000 residents, the law upzones single-family lots to allow duplex construction.

In 2016, California policymakers passed a law that requires all the state’s localities to allow ADUs on all lots that have single-family homes. In Los Angeles particularly, the law has led to a surge in ADU permitting. Following the law’s passage, at least 2,500 new ADUs have been built in the city, representing a 1,000 percent increase in permitting.59Luis Arias, “Is the Answer to LA’s Housing Crisis in Your Backyard?,” LAist, August 8, 2019. In 2019, California policymakers took an additional step, allowing all homeowners to build second “junior” ADUs—effectively setting the lower bound of density restrictions in the state to triplex zoning.60A.B. 68, 2019–20 Leg., Reg. Sess. (California 2019). See also “AB-68 Land Use: Accessory Dwelling Units,” California Legislative Information, accessed May 5, 2020, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB68.

Following the principle of subsidiarity provides advantages in some areas of local policymaking, increasing voters’ options to live in a jurisdiction that matches their policy preferences. But land use regulations that prevent housing construction, thus reducing the potential for population growth, reduce residents’ opportunities to choose between jurisdictions. When land use decisions are made at the neighborhood or municipal level, the costs of construction tend to be emphasized rather than the long-term benefits of allowing more people to live in their location of choice. Therefore, states have an important role to play in protecting individual rights from local restrictions by limiting the extent to which localities may restrict housing construction.

Conclusion

In particularly exclusionary jurisdictions, local land use regulations stand in the way of new housing supply being built in response to new demand. This situation leads to the price for a fixed supply of housing being bid up. This, in turn, creates painful trade-offs for all kinds of households, but it particularly burdens low-income renters.

While some cities have successfully liberalized land use regulations, incentives are stacked against liberalization at the local level. Local policymakers are incentivized to please homevoters in order to stay in office, and homevoters are incentivized to oppose development in order to increase their property’s value through scarcity.

States have a role to play in limiting the extent to which localities constrain new housing construction, because the costs of housing supply constraints spill over across local borders. Municipalities derive from their states their authority to use their police power to protect their residents’ interests through land use regulations, so states should require that localities consider the interests of all the state’s residents when determining housing policy.

References

“2019 Session: House Bill 2001.” Your Government website (OregonLive.com). Accessed May 5, 2020. https://gov.oregonlive.com/bill/2019/hb2001/.

A.B. 68, 2019–20 Leg., Reg. Sess. (California 2019).

Aastveit, Knut Are, Bruno Albuquerque, and André Anundsen. “Time-Varying Housing Supply Elasticities and US Housing Cycles” (Working paper. January 31, 2018). https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=IAAE2018&paper_id=397.

“AB-68 Land Use: Accessory Dwelling Units.” California Legislative Information. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB68.

Andersen, Michael. “It’s Official: DC Politicians Have Woken Up to Housing Abundance.” Sightline Institute. October 14, 2019.

Arias, Luis. “Is the Answer to LA’s Housing Crisis in Your Backyard?” LAist. August 8, 2019.

Been, Vicki et al., “Preserving History or Hindering Growth? The Heterogeneous Effects of Historic Districts on Local Housing Markets in New York City” (NBER Working Paper 20446. National Bureau of Economic Research. September 2014).

Buchanan v. Warley. 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

“Buchanan v. Warley.” Oyez. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/245us60.

Caro, Robert. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf. 1974). 1024.

Cavanaugh, Kerry. “Holy Cow! California May Get Rid of Single-Family Zoning.” Los Angeles Times. April 24, 2019.

Diamond, Rebecca, Tim McQuade, and Franklin Qian. “The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco” (NBER Working Paper No. 24181. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. January 2018).

Ellen, Ingrid Gould, Brian J. McCabe, and Eric Edward Stern. “Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in New York City” (Fact Brief. Furman Center at New York University. March 2016).

Euclid v. Ambler. 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

Fischel, William A. “An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for Its Exclusionary Effects.” Urban Studies 41. No. 2 (February 2004).

Fischel, William A. “The Rise of the Homevoters: How OPEC and Earth Day Created Growth-Control Zoning That Derailed the Growth Machine” (working paper. Marron Institute. February 2016).

Fischel, William A. Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 2015). 229–30.

Fischler, Raphael. “Health, Safety, and the General Welfare: Markets, Politics, and Social Science in Early Land-Use Regulation and Community Design.” Journal of Urban History 24. No. 6 (September 1998): 675–719.

Ganong, Peter and Daniel Shoag. “Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined?” Journal of Urban Economics 102 (2017).

Glaeser, Edward L. and Joseph Gyourko. “The Economic Implications of Housing Supply.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 32. No. 1 (Winter 2018): 3–30.

Glaeser, Edward L., Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks. “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in House Prices” (NBER Working Paper No. 10124. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. November 2003).

Glynn, Chris and Alexander Casey. “Homelessness Rises Faster Where Rent Exceeds a Third of Income.” Zillow Research. December 11, 2018.

Gray, M. Nolan and Adam A. Millsap. “Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis of the Causes and Effects of Houston’s 1998 Subdivision Reform.” Journal of Planning and Education Research (2020).

Gray, Nolan and Salim Furth. “Do Minimum-Lot-Size Regulations Limit Housing Supply in Texas?” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. November 2015).

Groth, Paul. “Appendix: Hotel and Employment Statistics.” Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press. 1994).

Gyourko, Joseph and Raven Molloy. “Regulation and Housing Supply.” Gilles Duranton, J. Vernon Henderson, William C. Strange, eds. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics Volume 5. (2015): 1291-2.

Gyourko, Joseph and Raven Molloy. “Regulation and Housing Supply” (NBER Working Paper No. 20536. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. October 2014).

Gyourko, Joseph, Albert Saiz, and Anita Summers. “A New Measure of the Local Regulatory Environment for Housing Markets: The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index.” Urban Studies 45. No. 3 (March 2008): 693–729.

Gyourko, Joseph, Jonathan Hartley, and Jacob Krimmel. “The Local Residential Land Use Regulatory Environment across U.S. Housing Markets: Evidence from a New Wharton Index” (NBER Working Paper No. 26573. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. December 2019).

H.B. 2001, 80th Leg. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Oregon 2019).

Hamidi, Shima, Sadegh Sabouri, and Reid Ewing. “Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic?” Journal of the American Planning Association 86. No. 4 (June 2020). 495-509.

Hamilton, Emily. “Inclusionary Zoning and Housing Market Outcomes” (Mercatus Working Paper. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. September 2019).

Herkenhoff, Kyle F., Lee E. Ohanian, and Edward C. Prescott. “Tarnishing the Golden and Empire States: Land-Use Restrictions and the U.S. Economic Slowdown.” Journal of Monetary Economics 93 (2018): 89–109.

Holder, Sarah. “The Cities Where Job Growth Is Outpacing New Homes.” CityLab. September 9, 2019.

Holeywell, Ryan. “Forget What You’ve Heard, Houston Really Does Have Zoning (Sort Of).” Kinder Institute for Urban Research. September 8, 2015.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai and Enrico Moretti. “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics” 11. No. 2 (2019): 1-39.

Ihlanfeldt, Keith R. “The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices.” Journal of Urban Economics 61. No. 3 (2007): 420–35.

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1985). 192.

Jun, Myung-Jin. “The Effects of Portland’s Urban Growth Boundary on Housing Prices.” Journal of the American Planning Association 72. No. 2 (2006): 239–43.

King, Loren. “Cities, Subsidiarity, and Federalism.” Nomos 55 (2014): 291–331.

Kirp, David L., John P. Dwyer, and Larry A. Rosenthal. Our Town: Race, Housing, and the History of Suburbia (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press. 1997).

Knaap, Gerrit J. “The Price Effects of Urban Growth Boundaries in Metropolitan Portland, Oregon.” Land Economics 61. No. 1 (1985): 26.

Lionshead Lake, Inc. v. Township of Wayne. 10 N.J. 165, 89 A.2d 693 (1952).

Lockwood, Charles. Manhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976. Repr. Dover. 2014). 293.

Lovett, Ian, Dan Frosch, and Paul Overberg. “Covid-19 Stalks Large Families in Rural America.” The Wall Street Journal. June 7, 2020.

Mast, Evan. “The Effect of New Market-Rate Housing Construction on the Low-Income Housing Market.” (Upjohn Institute Working Paper 19-307. 2019).

Molotch, Harvey. “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” American Journal of Sociology 82. No. 2 (1976): 309–32.

Moore, Derrick. “Overall Mover Rate Remains at an All-time Low.” U.S. Census Bureau. December 21, 2017.

Owen, David. Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less Are the Keys to Sustainability (New York: Penguin. 2009).

Rosenthal, “Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing?”

Rosenthal, Stuart. “Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a ‘Repeat Income’ Model.” American Economic Review 104. No. 2 (February 2014): 687–706.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright. 2017).

Salviati, Chris. “Renters vs. Homeowners at the Ballot Box—Will America’s Politicians Represent the Voice of Renters?” Apartment List. October 30, 2018.

Schuetz, Jenny. “Cost, Crowding, or Commuting? Housing Stress on the Middle Class.” Brookings Institution. May 7, 2019.

Shoup, Donald C. The High Cost of Free Parking (Chicago: American Planning Association, 2011). 90.

Siegan, Bernard. Land Use without Zoning (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath. 1972). 88.

Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Township of Mount Laurel, 67 N.J. 151, 336 A.2d 713 (1975).

Stromberg, Brian and Lisa Sturtevant. “What Makes Inclusionary Zoning Happen?” (Inclusionary Housing policy brief. National Housing Conference. May 2016).

Toll, Seymour. Zoned American (New York: Grossman. 1969). 158-9.

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy