When the Metcalf-McCloskey Act of New York passed in 1964, the United States was seeing its first certificate-of-need (CON) law. This law allowed the state of New York to regulate “the exact [healthcare] needs of the community prior to hospital construction.”1Pamela C. Smith and Kelly Noe, “Is the Community Health Needs Assessment Replacing the Certificate of Need?,” Journal of Health Care Finance 42, no. 2 (Fall 2015). The New York legislators meant to control healthcare costs by limiting the construction of healthcare facilities and encouraging their spread across the state—maximizing access for those seeking medical treatment. In order to expand an existing facility or build a new facility, interested parties (e.g., physicians/entrepreneurs) had to file an application with the state.2Katelin Davis, “Modernizing Certificate of Need Laws to Match the Post–Affordable Care Act Landscape: Using Mississippi as a Case Study for Reform in Healthcare Costs and Access to Rural Care,” Mississippi Law Journal 89, no. 3 (2020): 479–523. Through these regulations, New York hoped to increase access to healthcare (especially in rural areas), increase the quality of care, and decrease healthcare spending.3James F. Blumstein and Frank A. Sloan, “Health Planning and Regulation through Certificate of Need: An Overview,” Utah Law Review 3 (1978): 37.

In 1974, the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act (NHPRDA) brought the idea of certificate-of-need to the federal government. Like New York’s law, this act implemented state agencies designated for the regulation of the building, expansion, and modernization of healthcare facilities and medical equipment.4James F. Blumstein and Frank A. Sloan, “Health Planning and Regulation through Certificate of Need: An Overview.” In an effort to encourage the development of healthcare facilities in rural and low-in- come areas, The NHPRDA allocated $1 billion (about $4.2 billion in 2020 money) over three years to aid in the expansion of healthcare through resource development and health planning.5“National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974, Pub. L. No. 93-641, 88 Stat. 2225 (1975). To be eligible for these funds, a community would need to implement its own CON law. Over the decade that followed, every state except Louisiana enacted some form of a CON law.6James Simpson, “State Certificate-of-Need Programs: The Current Status,” American Journal of Public Health 75, no. 10 (October 1985): 1225–29.

Motivated by the lack of evidence that CON laws restrained costs and by the Reagan administration’s deregulatory efforts, Congress, in 1986, repealed the federal requirement for CON laws in state health- care systems.7Simpson, “State Certificate-of-Need Programs: The Current Status.” Still, today the majority of states, 35, maintain CON laws.8“CON – Certificate of Need State Laws,” National Conference of State Legislatures, December 2019, accessed October 10, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/con-certificate-of-need-state-laws.aspx#:~:text=a%20community%20need.Interactive%20Map%20of%20State%20CON%20Laws,each%20state%20as%20December%202019.

In this chapter we discuss the effects on CON laws, which have been studied extensively ever since the first law was passed in New York. Researchers have documented effects on access to care, affordability of care, quality of care, and—in a few cases—health outcomes. In short, previous studies show that CON laws are ineffective at improving access, affordability, or quality of care. On the basis of these findings, we lay out several potential policy alternatives. In most cases, patients will be best served by the repeal of state-level CON laws in favor of experimentation by entrepreneurs. Where that is not possible, policymakers should consider modifications to current CON laws or other options, such as administrative relief, to allow for increased access to healthcare.

Access to high-quality health services and care is vital for the well-being of individuals in communities across the US. Despite the intentions of CON laws’ proponents, the evidence shows that the laws are more a barrier to achieving this goal than a pathway toward it.

What Are the Effects of Certificate-of-Need Laws?

Certificate-of-need laws were intended to support the expansion of healthcare by means of regulations that enhanced healthcare facilities and increased the use of medical devices. Many of the people who developed CON laws thought the laws could regulate costs to make healthcare more affordable and could facilitate the expansion of healthcare, allowing for accessible care in rural areas and optimizing the use of medical devices.9James F. Blumstein and Frank A. Sloan, “Health Planning and Regulation through Certificate of Need: An Overview,” Utah Law Review 3 (1978): 37. However, evidence suggests that the laws have instead reduced the quality, accessibility, and affordability of healthcare.

Quality of Care

A central goal of CON laws is to improve the quality of the care provided within the healthcare system.10James F. Blumstein and Frank A. Sloan, “Health Planning and Regulation through Certificate of Need: An Overview.” Yet surgical research results suggest that CON laws may contribute to higher mortality rates and reduce the quality of care. Reforming CON laws in states that still have them likely improves the quality of health, based on evidence collected before and after the removal of CON laws in several states.

Every year, approximately 790,000 knee replacement surgeries and 450,000 hip replacement surgeries are performed in the United States.11“Total Knee Replacement,” OrthoInfo (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons), accessed July 27, 2020, https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement/. (Since these are commonly performed surgeries, it may be more practical to observe how these are affected by CON laws.) One study of Pennsylvania’s CON law repeal in 1996 examined the surgical outcomes of knee and hip replacements. Researchers discovered that the rate of death related to knee and hip replacement surgeries declined after the CON law’s repeal.12Susan L. Averett, Sabrina Terrizzi, and Yang Wang, “Taking the CON Out of Pennsylvania: Did Hip/Knee Replacement Patients Benefit? A Retrospective Analysis,” Health Policy and Technology 8, no. 4 (December 2019): 349–55. It seems that if CON laws are removed elsewhere, their removal might correlate with an increase in longevity of life.

Cardiac care is another area that can be looked at to see the effects of CON laws. The researchers who conducted a different study focused on coronary artery bypass graft surgeries and found an increase in mortality rates prior to Pennsylvania’s CON law repeal.13David Cutler, Robert S. Huckman, and Jonathan T. Kolstad, “Input Constraints and the Efficiency of Entry: Lessons from Cardiac Surgery,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2, no. 1 (February 2010): 51–76. A similar study followed patients undergoing artery bypass surgery after the repeal of CON laws in multiple states. This study discovered that the removal of CON laws resulted in lower mortality rates. Additionally, there was no evidence suggesting that CON laws were associated with higher-quality care.14Vivian Ho, Meei-Hsiang Ku‐Goto, and James Jollis, “Certificate of Need (CON) for Cardiac Care: Controversy over the Contributions of CON,” Health Services Research 44, no. 2p1 (2009): 483–500. Overall, both of these surgical studies conclude that CON laws reduce the quality of care through their regulations and contribute to higher mortality rates.

An economic study of Vermont predicts that the quality of care would rise with the removal of CON laws: the researchers found a 4.5 percentage point increase in patient satisfaction rates. Perhaps more importantly, the study also suggests that eliminating CON laws would lower mortality rates.15Thomas Stratmann et al., “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, August 29, 2017, accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.org/publications/corporate-welfare/certificate-need-laws-how-con-laws-affect-spending-access-and-quality. A similar study for the state of Virginia found that if CON laws were repealed, the total number of post-surgery com- plications would decrease by 5.2 percent and patient satisfaction would increase by 4.7 percent.16Mercatus Center at George Mason University, “Certificate-of-Need Laws: Virginia State Profile,” accessed February 10, 2020, https://www.merorg/system/files/virginia_state_profile.pdf; Thomas Stratmann and David Wille, “Certificate-of-Need Laws and Hospital Quality” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, September 2016).

In a recent study, economists Thomas Stratmann and David Wille found that the CON law review process resulted in limited entry of fewer healthcare facilities and lower hospital quality.17Stratmann and Wille, “Certificate-of-Need Laws and Hospital Quality.” The study showed that nearly all the measures normally used to gauge hospital quality are worse in CON states. Importantly, this paper avoids concerns about reverse causality. In the case of CON laws, the reverse causality argument holds that it is poor health conditions or a lack of healthcare options that encourage the passage of CON laws. However, Stratmann and Wille’s study shows that it is CON laws that drive poor healthcare outcomes, and not the other way around. The study mitigates concerns about reverse causality by examining communities that span CON and non-CON states.18Stratmann and Wille, “Certificate-of-Need Laws and Hospital Quality.”

Supporters of CON laws believe restricting medical services, especially limiting the number of providers, will ensure that each provider has a higher number of patients –resulting in better quality of care.19Stratmann and Wille, “Certificate-of-Need Laws and Hospital Quality.” But this prediction relies on the assumption that the providers operating under CON laws will be more proficient and specialized since a specialization allows a physician to perform the same procedure often. However, this is not always the case. In fact, research has shown that the quality of care has no difference with physicians practicing in CON vs non-CON states.20Stratmann and Wille, “Certificate-of-Need Laws and Hospital Quality.” Ultimately, research has revealed that CON laws have negative impacts on mortality rates and quality of care. Removing or modifying CON laws may achieve an improvement in quality of care. This will lead to an increased opportunity for longevity and could result in greater economic growth. As long as CON laws remain, they will hinder efforts to achieve these goals—but this will not be their only effect. Accessibility to care is also affected in states with CON laws.

Accessibility of Care

CON laws were designed with the intent to increase access to healthcare. However, research has shown that CON laws, by limiting the ability of entrepreneurs to start medical businesses, have reduced access to care or at the most made no improvement.

Under CON laws it becomes more difficult for medical providers to obtain medical devices. This suggests that patients will experience both reduced quality and reduced accessibility of care. The evidence bears out this prediction: For example, one study found that states with CON laws experience decreased utilization of medical equipment (i.e., fewer MRI scans, CT scans, and PET scans) from nonhospital providers by 34 to 65 percent.21Thomas Stratmann and Matthew C. Baker, “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry? How They Affect Access to MRI, CT, and Pet Scans” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, January 2016). The rare use of these medical devices within CON states is likely due to the regulations for expanding current medical facilities. Because of these restrictions imposed by CON laws, it is difficult for entrepreneurs to expand medical facilities. A lack of medical facilities can encourage consumers to travel long distances, even out of state, to receive medical care where it is more accessible.22Stratmann and Baker, “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry? How They Affect Access to MRI, CT, and Pet Scans.” This generates a decline in medical equipment usage in states with CON regulations because consumers would rather travel outside of their state to receive efficient medical care, perpetuating the cycle. Also, the potential smaller selection of medical devices in CON-regulated states consequently forces patients to travel out of state for their medical care.

According to Thomas Stratmann and Matthew Baker (a PhD student at George Mason University), there are “3.93 percent more MRI scans, 3.52 percent more CT scans, and 8.13 percent more PET scans” occurring outside CON-regulated states.23Stratmann and Baker, “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry? How They Affect Access to MRI, CT, and Pet Scans.” Removing CON laws would decrease barriers to entry for medical providers and provide increased access to medical devices, improving healthcare overall for patients who need access to medical devices. Because CON laws limit access to medical equipment and services, they limit patients’ options. Patients facing a restricted supply are forced to travel further or wait longer for medical care.

The economic study of Vermont mentioned earlier estimates how the removal of CON laws would also provide more access to healthcare services. If CON laws were removed, there would be approximately six more hospitals available in Vermont (most in rural areas), 36.4 percent more MRI scans available, and 70 percent more CT scans available.24Thomas Stratmann et al., “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States.”, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, August 29, 2017, accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/corporate-welfare/certificate-need-laws-how-con-laws-affect-spending-access-and-quality. This study demonstrates an increase in accessibility with the removal of CON laws, but—like before—the increase can be more easily analyzed by looking at common surgical procedures.

A study by researchers at the University of Virginia revealed that fewer total hip replacement surgeries were performed in states that had CON laws, compared to their counterparts without CON laws.25Aaron J. Casp et al., “Certificate-of-Need State Laws and Total Hip Arthroplasty,” Journal of Arthroplasty 34, no. 3 (March 2019): 401–7. This suggests that CON laws likely play a role in inhibiting access to care. We have examined how CON laws hinder access to medical devices and to healthcare in general. Now we will see how the CON application process also creates barriers to providing healthcare services.

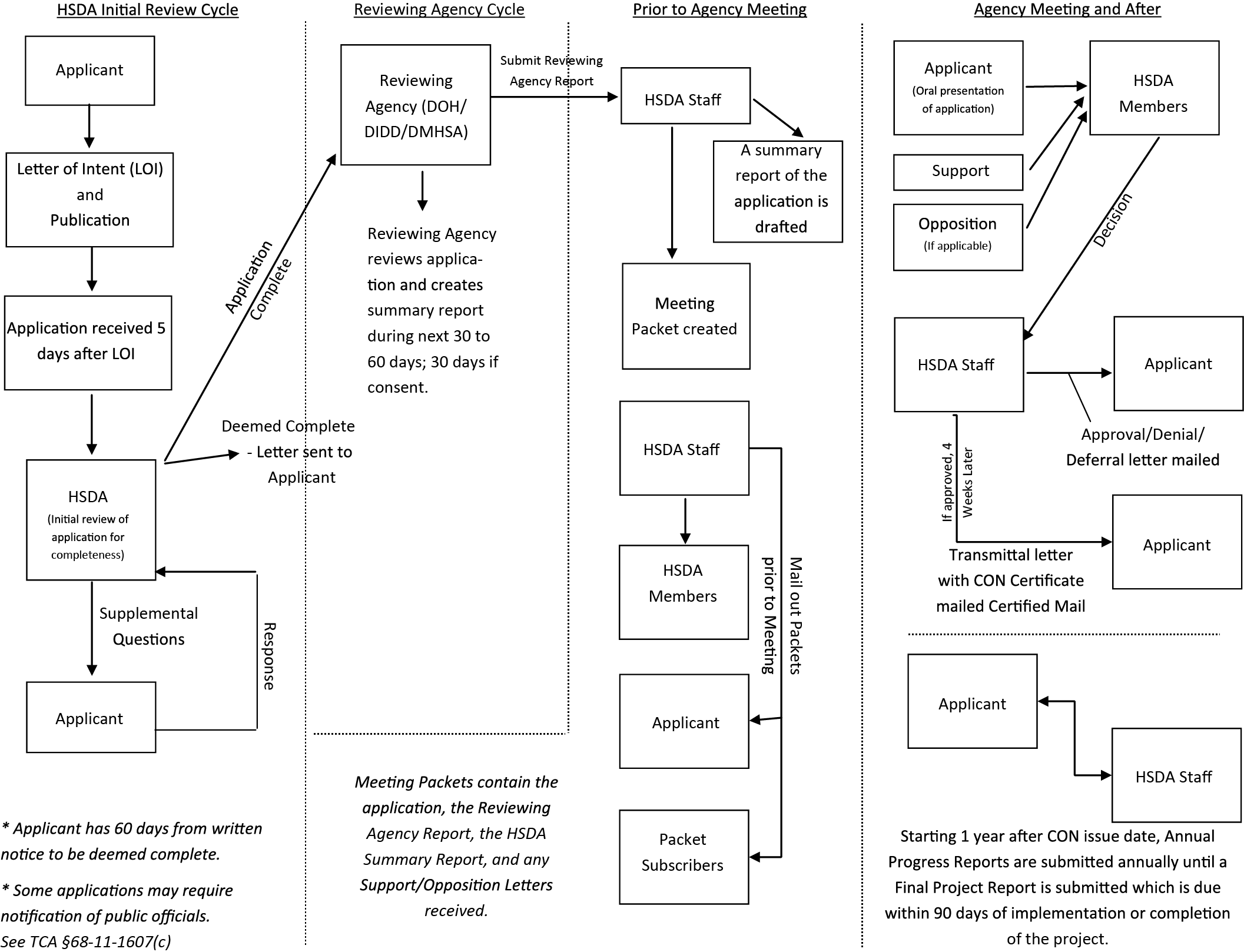

In Tennessee, entrepreneurs must jump through several hoops and wait on the decisions of state regulation agencies before they can build new facilities, expand existing facilities, or buy new medical devices. As shown in figure 1, the process begins when an applicant files a letter of intent with the state. (This letter must also be published in the newspaper.) The applicant must then pay a filing fee before the request goes under review by the Tennessee Health Services and Development Agency. The review process often results in additional questions for the applicant. The applicant’s responses are taken into consideration as the application enters a second cycle of review. Tennessee’s review cycle begins on the first of each month and can take approximately 60 days for applicants to receive an approval or denial of their application. If the application is denied, the applicant may appeal within 15 days from their initial notification. If the application is approved, it can take an additional four weeks for the applicant to receive their certification. Once the certificate has arrived the changes requested in the application can be made.26“CON Process and How to Apply,” Tennessee Health Services and Development Agency, accessed January 30, 2020, https://www.tn.gov/hsda/certificate-of-need-information/how-to-apply-for-con.html.

This lengthy process delays projects that would increase access to care and means entrepreneurs have weaker incentives to expand existing facilities. The entire CON application process in the state of Tennessee can take anywhere from 65 to 110 days.27Applications can take 110 days if they are initially rejected and the applicant chooses to appeal. Figure 1 illustrates how the complexity of the application process might be one reason why many potential entrepreneurs are hesitant to begin the process.

In order to help improve the accessibility of care, states should consider removing the long review process. Without the applications, fees, waiting times, and associated frustrations, facilities would be able to enter the construction phase sooner and would therefore be available to provide more care to their communities. Thanks to this increase in care and accessibility, there would be more opportunity for competition. This increased competition would incentivize entrepreneurs to expand medical facilities and equipment within each formerly regulated state and encourage those seeking medical attention to stay inside state lines—bolstering the state’s economy.

Figure 1. Tennessee Certificate-of-Need Application Process

Note: DOH = Tennessee Department of Health, DIDD = Tennessee Department of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, DMHSA = Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services Agency, HSDA = Tennessee Health Services and Development Agency.

Source: Flowchart published by the Tennessee Health Services and Development Agency, accessed October 2, 2020, https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/hsda/documents/con_process_flow_chart2014.pdf.

Affordability of Care

Despite CON law proponents’ intentions, research suggests that the laws have failed to make healthcare affordable. In terms of geographic proximity and in terms of financial costs, CON laws have made care less accessible and less affordable. An early indication of the limitations of CON laws can be found in a thorough 1988 report conducted by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). In its review, the FTC found that healthcare costs were not lower after CON laws were enacted.28Daniel Sherman, “The Effect of State Certificate-of-Need Laws On Hospital Costs: An Economic Policy Analysis,” Federal Trade Commission (1988): 97. In fact, contrary to what the law’s proponents had anticipated, many of the states that had incorporated CON laws appeared to have higher healthcare spending than states that did not enforce CON laws.29Sherman, “The Effect of State Certificate-of-Need Laws On Hospital Costs: An Economic Policy Analysis.”

Ophthalmology, the branch of medicine that deals with eyes, illustrates why CON law modifications or removal can increase affordability of care. Ophthalmology is still regulated under CON laws, however, this focus of medicine seems to have a higher probability of building and using existing ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs). ASCs were first developed due to physician frustrations with local hospitals.30Carolina Ophthalmology, P.A., “Petition for a change in the basic policies and methodologies for the 2009 state medical facilities plan,” North Carolina Division of Health Service Regulation (2008) : 18. Physicians had a difficult time finding the resources needed to perform their surgeries at hospitals so they developed ASCs.31Carolina Ophthalmology, P.A., “Petition for a change in the basic policies and methodologies for the 2009 state medical facilities plan.” The use of ASCs is increasing in ophthalmology. Between 2001 and 2014, the use of ASCs (particularly for cataract surgery) has grown by 2.34 percent each year.32Brian C. Stagg et al., “Trends in Use of Ambulatory Surgery Centers for Cataract Surgery in the United States, 2001–2014,” JAMA Ophthalmology 136, no. 1 (January 2018): 53–60. This shift from hospitals to ASCs increases accessibility for eye surgeries and drives down their costs for patients (and insurers) because of gains in convenience.33Stagg et al., “Trends in Use of Ambulatory Surgery Centers for Cataract Surgery in the United States, 2001–2014.”; Muayad Kadhim et al., “Do Surgical Times and Efficiency Differ between Inpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Centers That Are Both Hospital Owned?,” Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 36, no. 4 (2016): 423–28; David Shactman, “Specialty Hospitals, Ambulatory Surgery Centers, and General Hospitals: Charting a Wise Public Policy Course,” Health Affairs 24, no. 3 (2005): 868–73; Aparna Higgins, German Veselovskiy, and Jill Schinkel, “National Estimates of Price Variation by Site of Care,” American Journal of Managed Care 22, no. 3 (2016): e116–e121. If CON laws were removed this could increase the number of ASCs, provide more resources to physicians (decreasing frustrations), and increase affordability for patients.

Cataract surgeries provide a good example of how costs can be brought down while a procedure remains easily accessible. Cataract surgery is a procedure that removes the natural crystalline lens in the eye and replaces it with an artificial lens.34Geetha Davis, “The Evolution of Cataract Surgery,” Missouri Medicine 113, no. 1 (2016): 58–62. Historically, cataract surgery has been performed mostly in hospitals. Over the past few decades, however, this has changed. Most cataract surgeries are now performed in ASCs. This shift from hospitals to ASCs has instigated a decline in costs for the procedure. For example, in 2014 the average co-pay for a cataract removal in an ASC was $190, compared to $350 in a hospital.35“Increased Use of Ambulatory Surgery Centers for Cataract Surgery,” Michigan Medicine, November 22, 2017. Cataract surgeries are not the only eye procedures that highlight CON laws’ failings—cosmetic eye surgeries also provide a great example. Laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis, better known as LASIK, has become a popular cosmetic surgery for many citizens in the United States. In 2010 approximately 800,000 LASIK surgeries and similar procedures were performed.36“History of LASIK: Invention, Iteration & Current Status,” NVISION Eye Centers, accessed January 14, 2020, https://www.nvisioncenters.com/lasik/history-and-invention/. As technology improves and the market becomes more saturated with LASIK providers, the cost of LASIK declines. LASIK’s decrease in price is also influenced by the transparency of the market.37Sarah Gantz, “How Lasik and Botox Could Point the Way to Health Care Price Transparency,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 28, 2018. For example, many businesses showcase the price of their LASIK procedures, encouraging competitive pricing. Some businesses even offer specials as cheap as $250 per eye in order to attract patients. This allows consumers to find the best option available to them.

One reason this procedure fosters a competitive market is the nature of the surgery. LASIK is an elective procedure, meaning the patient has the choice to undergo the surgery or not. Many insurers do not cover the cost of LASIK; others cover only a minimal amount. Therefore, individuals contemplating LASIK surgery have an incentive to consider the cost as well as the safety of the facility they choose to perform the procedure. CON laws do not allow such competition to arise around other healthcare procedures (many of which are urgent or non-elective), so patients and providers do not have similar incentives to decrease the costs. Theoretically, the removal of CON laws could allow more competition within the healthcare market and provide an incentive to decrease costs for other areas of healthcare.

Unfortunately, there are rare circumstances in which strict CON laws do not allow for ASCs. In 2017, a doctor in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was unable to use an already-constructed ASC because the facility was denied certification. The doctor applied for certification four times, each time explaining the need for the ASC and demonstrating how the facility would provide for the community. However, the state denied each application. Iowa’s Hospital Association pointed out that the facility would take paying patients away from hospitals.38Forrest Saunders, “Cedar Rapids Doctor Fights State over Certificate of Need Requirements,” KCRG.com, June 14, 2017. Some studies demonstrate that preexisting facilities don’t lose patients when new facilities are opened, however39Thomas Stratmann and Christopher Koopman, “Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care: Certificate-of-Need Laws, Ambulatory Surgical Centers, and Community Hospitals” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, February 2016).—and even if they did, their loss might indicate that patients are receiving better care and services.

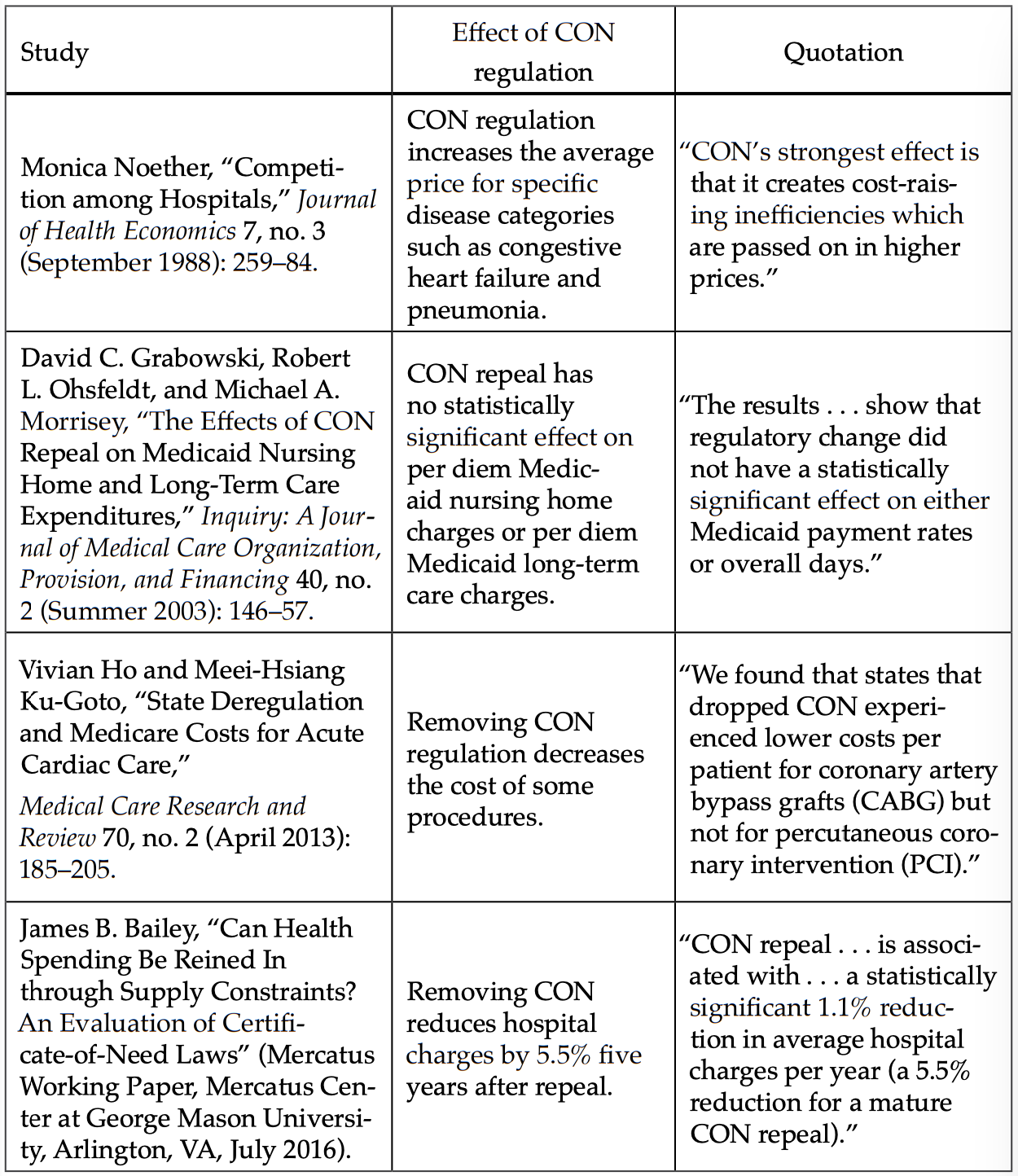

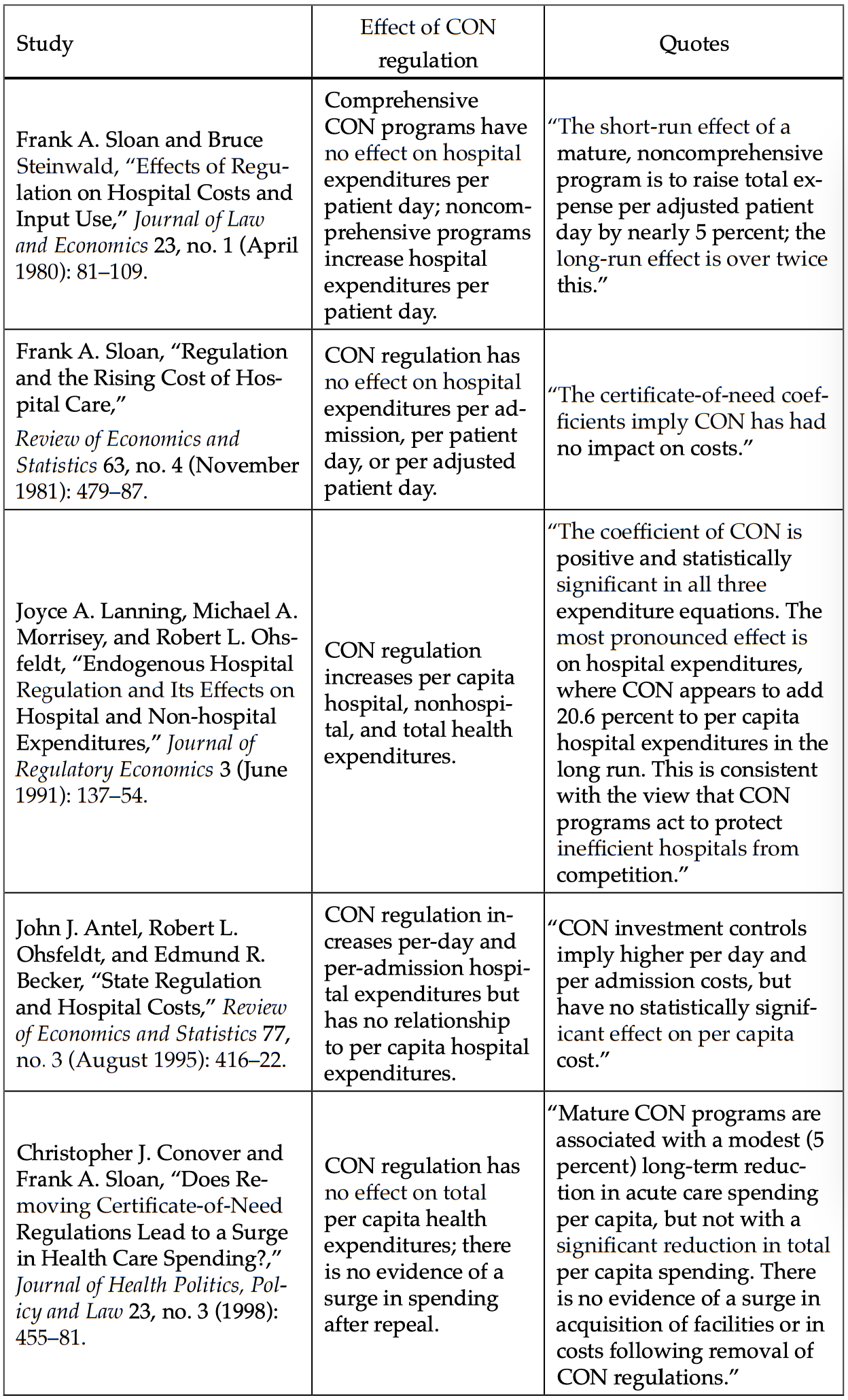

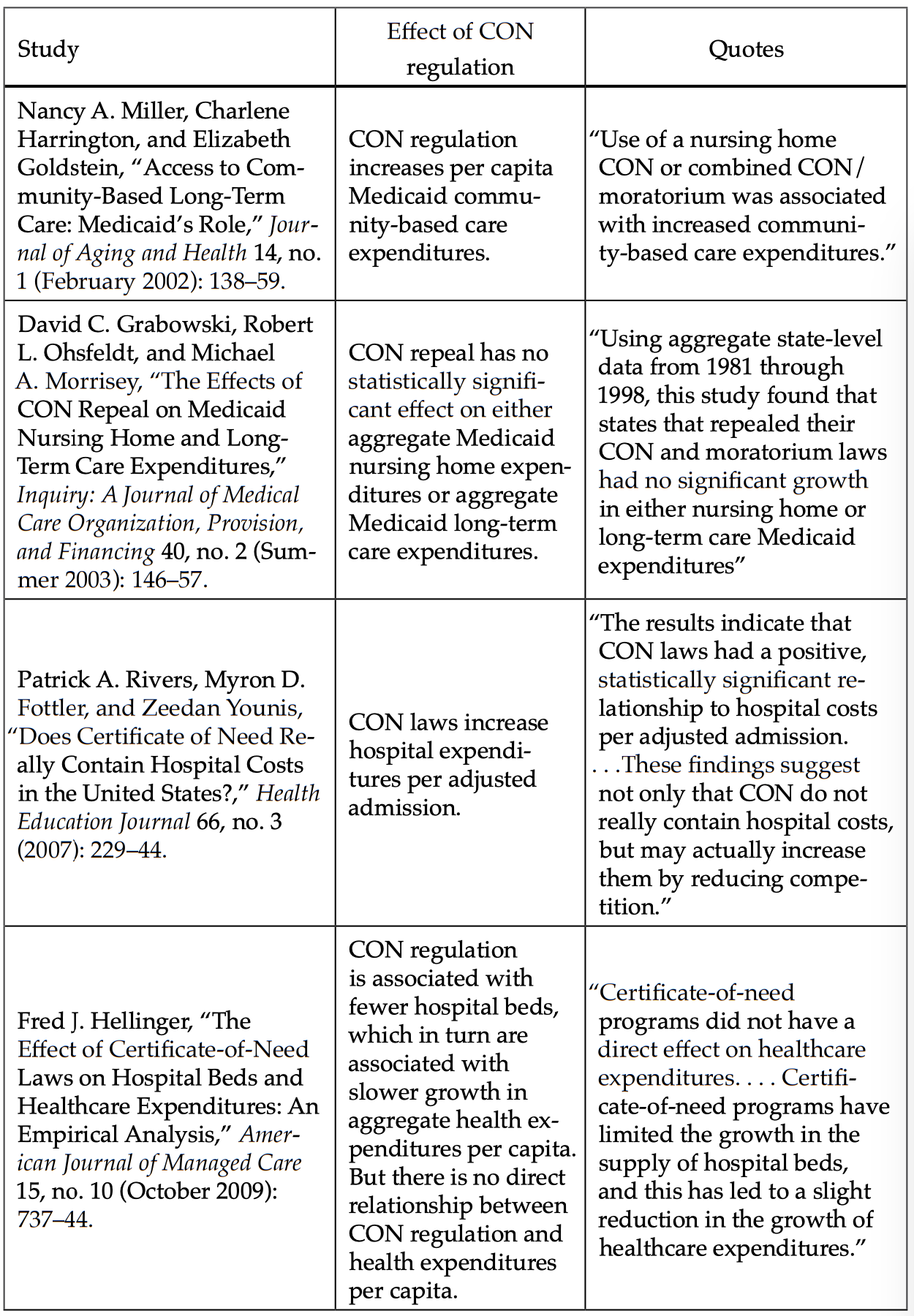

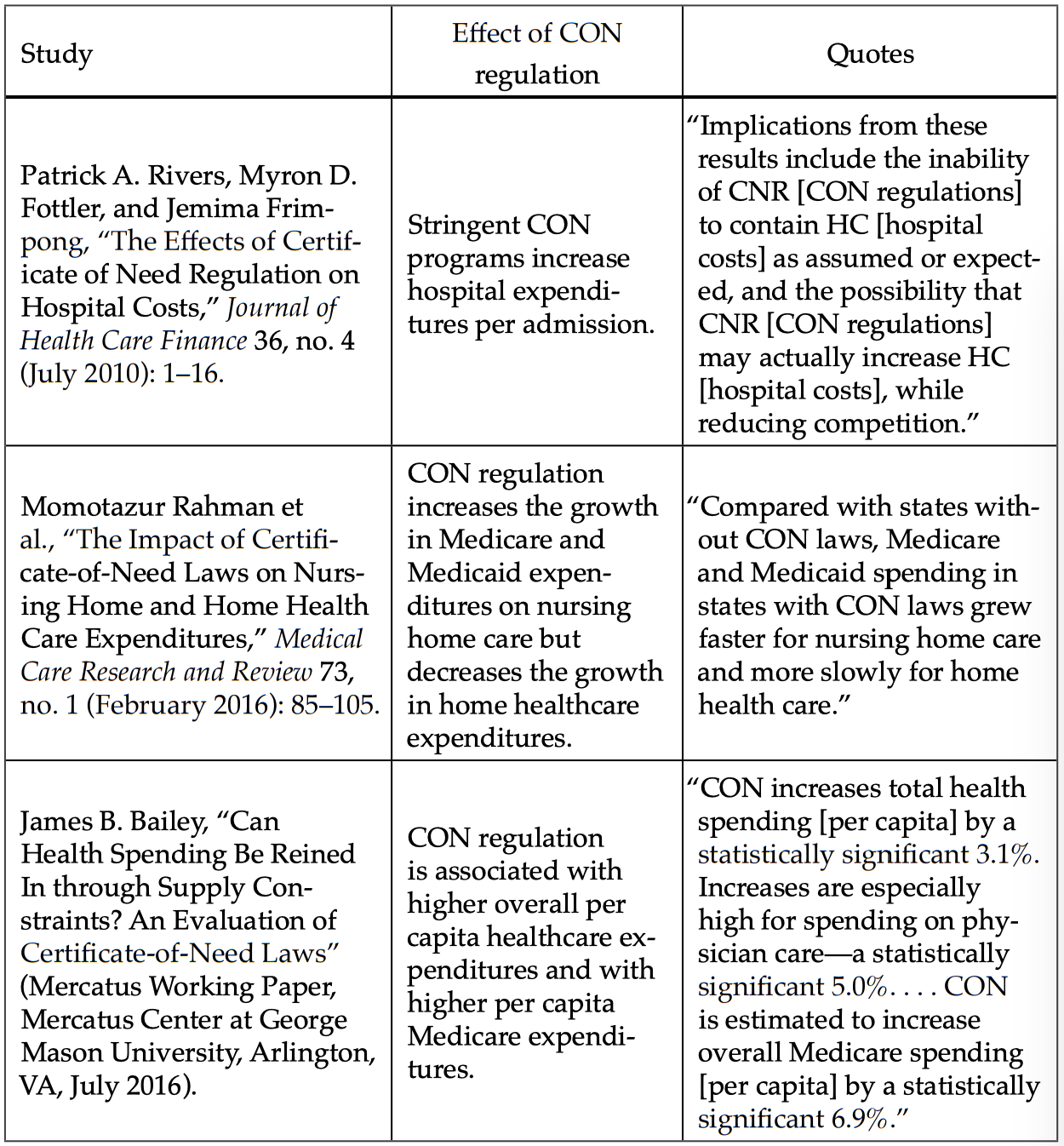

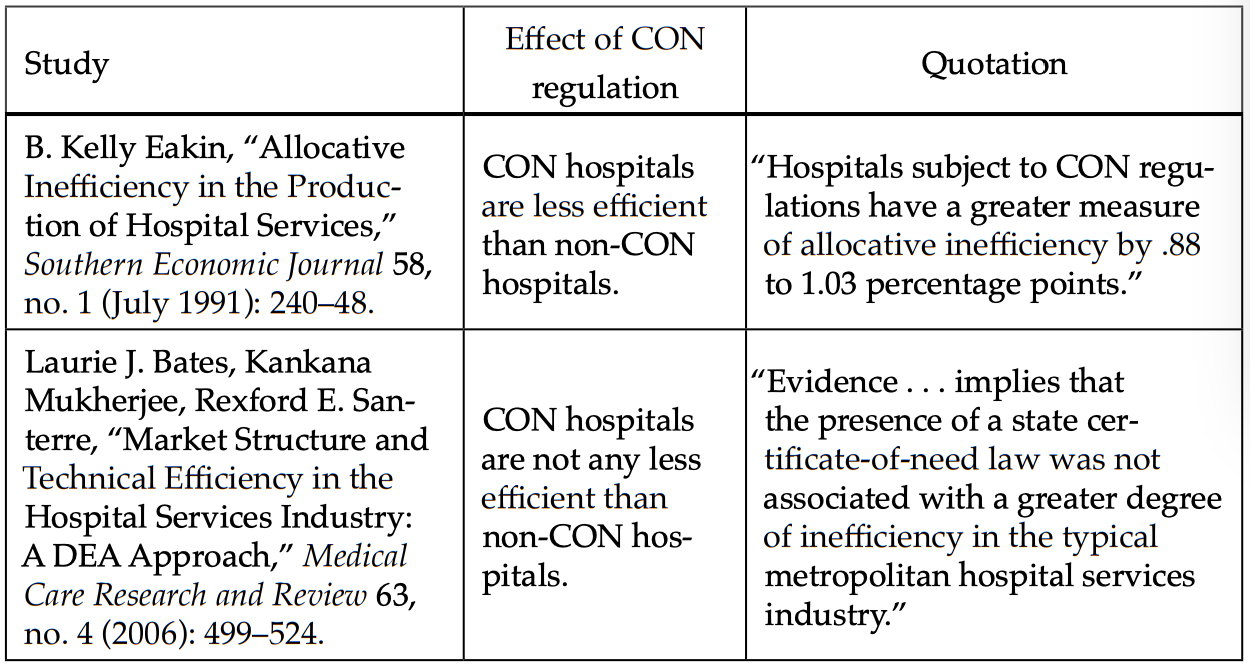

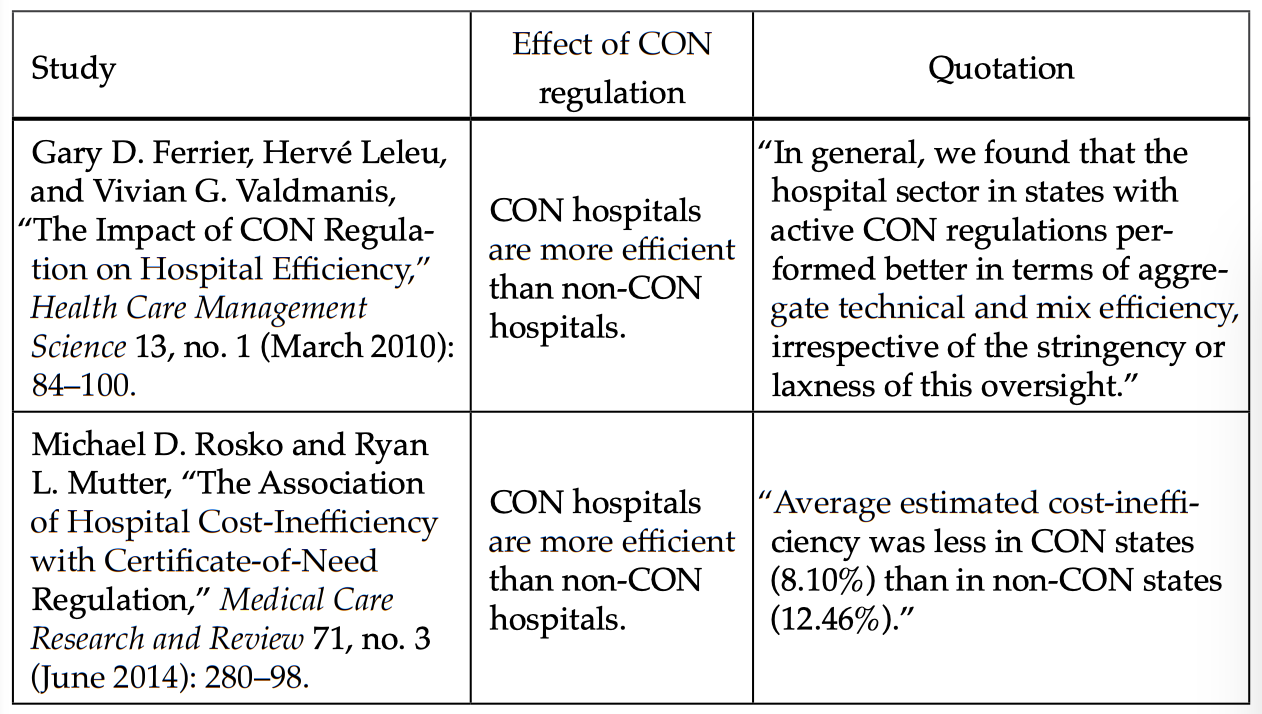

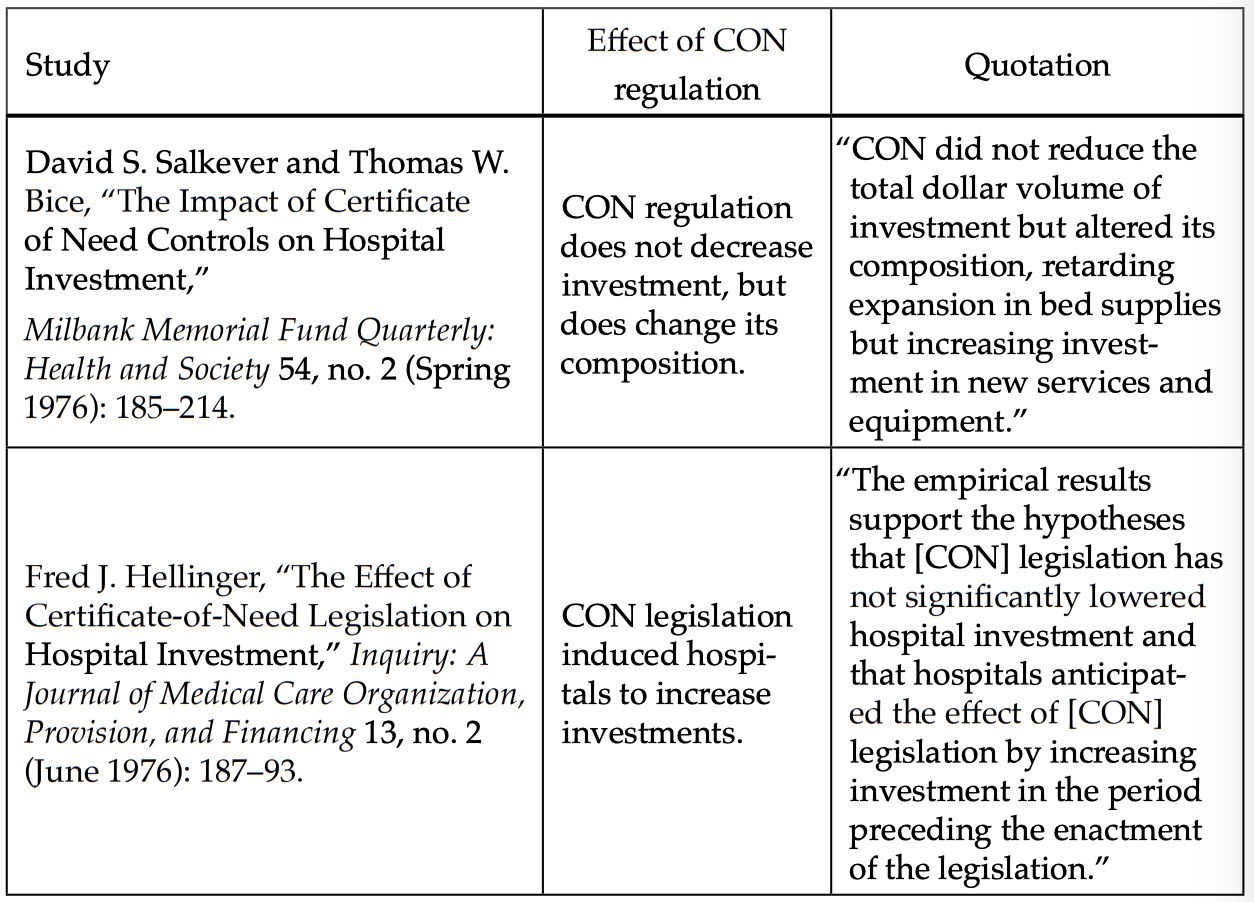

Many studies have found results suggesting that CON laws have failed to lower healthcare costs. These results, reported in the appendix, confirm the FTC’s earlier findings that CON laws increase healthcare costs.40Matthew Mitchell, “Do Certificate-of-Need Laws Limit Spending?” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, September 2016). (The tables in the appendix summarize how CON laws affect spending and efficiency.) Overall, 13 of the studies included in the appendix show that CON laws increase healthcare costs or decrease efficiency. The other 9 show no effect on healthcare costs, or show that CON laws improve efficiency. Both the FTC’s 1988 report and this more recent review of the research suggest that CON laws are at least questionable as a means of reducing healthcare costs.

Other studies continue to find similar results. For example, studies of Vermont and Virginia suggest that CON laws raise the prices of healthcare services in both states. According to estimates for Vermont, the removal of CON laws may reduce healthcare costs $228 per capita, and would decrease healthcare spending per physician per year by $68.41Stratmann et , “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, August 29, 2017, accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/corporate-welfare/certificate-need-laws-how-con-laws-affect-spending-access-and-quality. In the case of Virginia, the removal of CON laws would reduce spending by $79 per physician per year, and also would lower total healthcare spending by $205 per capita.42Stratmann et , “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States.” The authors of these two studies points out that this decline in healthcare costs happens because there are fewer restrictions to providing more healthcare services.

CON laws are not the only factor raising healthcare costs, however. Economists James Bailey and Tom Hamami have found that, on a national level (during 1996 – 2019), 10.5 percent of the increase in per capita healthcare spending was associated with CON laws.43James Bailey and Tom Hamami, “Competition and Health-Care Spending: Theory and Application to Certificate of Need Laws” (Working Paper 19-38, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, October 2019). To put this into perspective, for every dollar spent, approximately 10 cents could be saved by the removal of CON laws. This shows that the removal of CON laws has a significant effect on healthcare costs overall and could help improve access to care.

If CON laws were modified to encourage competition within the healthcare market, entrepreneurs would have an incentive to increase price transparency and provide lower-cost services. Recall how competition works: If store A sells a soda for one dollar, its competitor, store B, will want to sell the same product for 99 cents. This will encourage store A to lower its price to 98 cents. The back-and-forth will eventually level out and each store will charge the same price for a soda. This model could apply to the healthcare industry as well, if government policies encourage healthy competition to lower the cost of healthcare services and provide more affordable healthcare.

A Blueprint for Better Access and Higher-Quality Healthcare Services

Research suggests a number of alternatives to CON laws that will be more effective at providing access to high-quality healthcare services. They range from a full repeal of CON laws to changing how CON laws currently work.

The most straightforward policy response to the failures of CON laws is repeal. As of January 2020, 35 states maintain some kind of CON program. The positive experiences of the states that have repealed their own CON laws suggest that repeal improves access to healthcare and results in better-quality care at a lower cost.44Stratmann et al., “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States.” Research shows that states that have removed CON laws do not experience a surge of healthcare spending and tend to see improved access to healthcare facilities.45Christopher J. Conover and Frank A. Sloan, “Does Removing Certificate-of-Need Regulations Lead to a Surge in Health Care Spending?,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, Vol 23, no.3 (June 1998).

A second-best response is to modify existing CON laws. Such modifications have included near-repeal (see, e.g., Florida46Gary Scott Davis, Adam J. Rogers, and Carole M. Becker, “Florida Repeals Significant Portions of Certificate of Need Law,” National Law Review 9, no. 182 (July 2019).) and a process of phasing out the laws over time (see, e.g., Georgia47Andrew Whitney, “Georgia Pares Back CON Laws,” Heartland Institute, May 31, 2019.), among other approaches. States should revise their regulations to prevent the denial of modifications to existing medical facilities because of economic costs. If a state is unable to repeal its CON laws entirely, then it should clarify that the only acceptable reason for denying applications to build new facilities, expand current medical facilities, or purchase additional medical technologies and tools are that existing facilities are lacking optimal capacity and use. In other words, the current medical facilities are not seeing a high volume of patients so the need for a new facility or expansion of a current facility may not be justifiable.

In 2020, nine states have introduced legislation to modify their current CON laws.48Jack Pitsor, “States Modernizing Certificate of Need Laws,” LegisBrief (National Conference of State Legislatures) 27, no. 41 (December 2019). These bills have taken a number of forms. Florida’s, for example, removed the CON application requirement for several types of providers. The legislation exempted general hospitals, com- plex medical rehabilitation beds, and tertiary hospital services from the application and state-level approval process.49Gary Scott Davis, Adam J. Rogers, and Carole M. Becker, “Florida Repeals Significant Portions of Certificate of Need Law,” National Law Review 9, no. 182 (July 2019).Georgia’s legislation increased the expenditure threshold for facilities from $2.5 million to $10 million, and for medical equipment from $1 million to $3 million. This means that some healthcare expansions that would formerly have been contingent on CON approval can now avoid the CON application process.50Andrew Whitney, “Georgia Pares Back CON Laws,” Heartland Institute, May 31, 2019. While there is no evidence yet about how this change will affect the application process, the hope is that there will be fewer CON applications and an increase in healthcare innovation. For example, a brand-new MRI machine can cost up to $3 million.51Lacie Glover, “Why Does an MRI Cost So Darn Much?,” Money, July 16, 2014. Under the new legislation, a facility that wants to add a machine will no longer have to go through a CON application process and be approved.

Maryland is following in Florida and Georgia’s footsteps. The Maryland Health Care Commission did extensive research on CON laws and how they affected the healthcare system in the state.52Maryland Health Care Commission, “Modernization of the Maryland Certificate of Need Program: Final Report,” draft, December 11, 2018. One suggestion the commission came up with was to remove the expenditure threshold altogether. This would allow physicians to expand their current facilities without the hassle of trying to optimize their resources to fit under a specific monetary parameter.53Maryland Health Care Commission, “Modernization of the Maryland Certificate of Need Program: Final Report.” Maryland’s decision to modify its CON laws is a step in the right direction and will hopefully allow more access in areas where healthcare seems scarce.

Another minor, but perhaps meaningful, reform proposal is to wrap a CON process within existing community health needs assessment requirements.54Pamela C. Smith and Kelly Noe, “Is the Community Health Needs Assessment Replacing the Certificate of Need?,” Journal of Health Care Finance 42, no. 2 (Fall 2015). When the Affordable Care Act was passed, Congress required hospitals to fill out a community health needs assessment (a form provided through the IRS). This document assesses the community impact a hospital provides and if the hospital can justify their community impact they can maintain a tax-exempt status. This document helps identify opportunities to improve the healthcare services within a community by requiring hospitals to implement strategies to meet the health needs of that community; in this way they are similar to CON laws. Combining the two would eliminate the need to enforce CON laws because the health needs assessment identifies areas of need within the healthcare system, making CON laws redundant.55Smith and Noe, “Is the Community Health Needs Assessment Replacing the Certificate of Need?”

Repealing CON laws through interstate agreements is another option that may appeal to those who defend CON laws.56Matthew D. Mitchell, Elise Amez Droz, and Anna K. Parsons, “Phasing Out Certificate-of-Need Laws: A Menu of Options” (Policy Brief, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, February 2020). Colorado and Arkansas have already decided to repeal their CON laws if other states are willing to also repeal their CON laws.57Mitchell, Droz, and Parsons, “Phasing Out Certificate-of-Need Laws.” This type of agreement is not uncommon among states. For example, Utah has a similar interstate agreement in regards to Daylight Saving Time.58Daylight Saving Time Amendments, S.B. 59, 2020 Gen. Sess. (Utah 2020). According to the bill, the state house and senate must approve the bill in addition to “four other western states” in order for Utah to have year-round standard time.59Daylight Saving Time Amendments, S.B. 59. Using this type of alternative approach to address CON laws may be beneficial because it could influence neighboring states to follow suit.

A fifth option that could save time and money for those involved in the CON application process is administrative relief.60Mitchell, Droz, and Parsons, “Phasing Out Certificate-of-Need Laws.” Examples of administrative relief include fee reduction and a simplified application process.61Mitchell, Droz, and Parsons, “Phasing Out Certificate-of-Need Laws.” As mentioned earlier, the current Tennessee CON application process is quite complex. It can take months for an application to be approved and thousands of dollars to apply. This CON application process is similar in other CON regulated states as well. If the fees were significantly reduced and the application process were made much simpler, there might be an increase in applications—and eventually an increase in the healthcare system’s accessibility.

One final recommendation that may assist with CON reform is early temporary suspension of CON laws during an emergency (i.e., a pandemic). On March 11, 2020, the United Nations and the World Health Organization declared a pandemic of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.62“Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)—Events as They Happen,” World Health Organization, accessed May 31, 2020, https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen; “Coronavirus Global Health Emergency: Coverage from UN News,” UN News, accessed May 31,2020, https://news.un.org/en/events/coronavirus-global-health-emergency-coverage-un-news?page=45. Because of the limitations imposed by CON laws, many states were unprepared for the increased need of healthcare during the pandemic.

While many states (e.g., New York, Tennessee, Virginia, Georgia) temporarily suspended their CON laws in spring 2020, their response was not quick enough to handle the COVID-19 outbreak.63“States Are Suspending Certificate of Need Laws in the Wake of COVID-19 but the Damage Might Already Be Done,” Pacific Legal Foundation (blog), March 31, 2020. New York, for example, suspended its CON laws in mid-March, but this gave healthcare providers only one week to prepare for the exponential growth in demand that they were about to experience.64Angela C. Erickson, “States Are Suspending Certificate of Need Laws in the Wake of COVID-19 but the Damage Might Already Be Done,” Pacific Legal Foundation (blog), March 31, 2020. According to a 2018 study, there are approximately 2.8 hospital beds per 1,000 people in the United States.65Justin Haskins, “America’s Hospitals Are Unprepared for Coronavirus—Here’s Why You Should Blame Government,” The Hill, March 21, 2020. Compared to other countries this number is terribly low: for example, China has 4.3 beds per 1,000 and France has 6.5 beds per 1,000.66Haskins, “America’s Hospitals Are Unprepared.” If states decide to retain their CON laws after the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be worthwhile for them to investigate the pre and post effects the temporary suspension had on healthcare accessibility and cost.

Conclusion

When certificates of need were first introduced, they were intended to increase equity in healthcare. Although they were well intentioned, these policies have contributed to increased healthcare costs and limited access to healthcare.

Research suggests that CON laws do not support the expansion of healthcare services that communities and patients desperately need. Overall, the best policy for improving access to care and attaining higher-quality care is to remove CON laws. For states where a full repeal is unachievable, an alternative strategy is to modify CON laws by allowing for more capital expenditure for existing facilities. Georgia’s and Maryland’s experiences with this strategy appear promising.

Access to high-quality healthcare services is vital for the well-being of individuals in communities across the US. Despite the intentions of their proponents, CON laws are more of a barrier to these goals than a pathway toward better health outcomes. Policymakers should pursue reforms that either remove CON laws or bring them into line with their intended outcomes of increased accessibility and lowered healthcare costs.

Appendix: Empirical Studies of Certificate-of-Need Regulation and Health Spending

Effect of CON Regulation on Per Unit Costs, Prices, or Charges

Effect of CON Regulation on Expenditures

Effect of CON Regulation on Hospital Efficiency

Effect of CON Regulation on Investment

Source: Matthew D. Mitchell, “Do Certificate-of-Need Laws Limit Spending?” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, September 2016).

References

Averett, Susan L., Sabrina Terrizzi, and Yang Wang. “Taking the CON Out of Pennsylvania: Did Hip/Knee Replacement Patients Benefit? A Retrospective Analysis.” Health Policy and Technology 8. No. 4 (December 2019): 349–55.

Bailey, James and Tom Hamami. “Competition and Health-Care Spending: Theory and Application to Certificate of Need Laws” (Working Paper 19-38. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. October 2019).

Blumstein, James F. and Frank A. Sloan. “Health Planning and Regulation through Certificate of Need: An Overview.” Utah Law Review 3 (1978): 37.

Carolina Ophthalmology, P.A. “Petition for a change in the basic policies and methodologies for the 2009 state medical facilities plan.” North Carolina Division of Health Service Regulation (2008): 18.

Casp, Aaron J. et al. “Certificate-of-Need State Laws and Total Hip Arthroplasty.” Journal of Arthroplasty 34. No. 3 (March 2019): 401–7.

“CON – Certificate of Need State Laws.” National Conference of State Legislatures. December 2019. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/con-certificate-of-need-state-laws.aspx#:~:text=a%20community%20need,Interactive%20Map%20of%20State%20CON%20Laws,each%20state%20as%20December%202019.

“CON Process and How to Apply.” Tennessee Health Services and Development Agency. Accessed January 30, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/hsda/certificate-of-need-information/how-to-apply-for-con.html.

Conover, Christopher J. and Frank A. Sloan. “Does Removing Certificate-of-Need Regulations Lead to a Surge in Health Care Spending?” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law. Vol 23. No.3 (June 1998).

“Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)—Events as They Happen.” World Health Organization. Accessed May 31, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

“Coronavirus Global Health Emergency: Coverage from UN News.” UN News. Accessed May 31, 2020. https://news.un.org/en/events/coronavirus-global-health-emergency-coverage-un-news?page=45.

Cutler, David M., Robert S. Huckman, and Jonathan T. Kolstad. “Input Constraints and the Efficiency of Entry: Lessons from Cardiac Surgery.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2. No. 1 (February 2010): 51–76.

Davis, Gary Scott, Adam J. Rogers, and Carole M. Becker. “Florida Repeals Significant Portions of Certificate of Need Law.” National Law Review 9. No. 182 (July 2019).

Davis, Gary Scott, Adam J. Rogers, and Carole M. Becker. “Florida Repeals Significant Portions of Certificate of Need Law.” National Law Review 9. No. 182 (July 2019).

Davis, Geetha. “The Evolution of Cataract Surgery.” Missouri Medicine 113. No. 1 (2016): 58–62.

Davis, Katelin. “Modernizing Certificate of Need Laws to Match the Post–Affordable Care Act Landscape: Using Mississippi as a Case Study for Reform in Healthcare Costs and Access to Rural Care.” Mississippi Law Journal 89. No. 3 (2020): 479–523.

Daylight Saving Time Amendments. S.B. 59. 2020 Gen. Sess. (Utah 2020).

Erickson, Angelica C. “States Are Suspending Certificate of Need Laws in the Wake of COVID-19 but the Damage Might Already Be Done.” Pacific Legal Foundation (blog). March 31, 2020.

Gantz, Sarah. “How Lasik and Botox Could Point the Way to Health Care Price Transparency.” Philadelphia Inquirer. February 28, 2018.

Glover, Lacie. “Why Does an MRI Cost So Darn Much?” Money. July 16, 2014.

Haskins, Justin. “America’s Hospitals Are Unprepared for Coronavirus—Here’s Why You Should Blame Government.” The Hill. March 21, 2020.

Higgins, Aparna, German Veselovskiy, and Jill Schinkel. “National Estimates of Price Variation by Site of Care.” American Journal of Managed Care 22. No. 3 (2016): e116–e121.

“History of LASIK: Invention, Iteration & Current Status.” NVISION Eye Centers. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.nvisioncenters.com/lasik/history-and-invention/.

Ho, Vivian, Meei-Hsiang Ku Goto, and James G. Jollis. “Certificate of Need (CON) for Cardiac Care: Controversy over the Contributions of CON.” Health Services Research 44. No. 2p1 (2009): 483–500.

“Increased Use of Ambulatory Surgery Centers for Cataract Surgery.” Michigan Medicine. November 22, 2017.

Kadhim, Muayad et al. “Do Surgical Times and Efficiency Differ between Inpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Centers That Are Both Hospital Owned?” Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 36. No. 4 (2016): 423–28.

Maryland Health Care Commission. “Modernization of the Maryland Certificate of Need Program: Final Report.” Draft. December 11, 2018.

Mercatus Center at George Mason University. “Certificate-of-Need Laws: Virginia State Profile.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/virginia_state_profile.pdf.

Mitchell, Matthew D. “Do Certificate-of-Need Laws Limit Spending?” (Mercatus Working Paper. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA, September 2016).

Mitchell, Matthew D., Elise Amez Droz, and Anna K. Parsons. “Phasing Out Certificate-of-Need Laws: A Menu of Options” (Policy Brief. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. February 2020).

“National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974.” Pub. L. No. 93-641, 88 Stat. 2225 (1975).

Pitsor, Jack. “States Modernizing Certificate of Need Laws.” LegisBrief (National Conference of State Legislatures) 27. No. 41 (December 2019).

Saunders, Forrest. “Cedar Rapids Doctor Fights State over Certificate of Need Requirements.” KCRG.com. June 14, 2017.

Shactman, David. “Specialty Hospitals, Ambulatory Surgery Centers, and General Hospitals: Charting a Wise Public Policy Course.” Health Affairs 24. No. 3 (2005): 868–73.

Sherman, Daniel. “The Effect of State Certificate-of-Need Laws On Hospital Costs: An Economic Policy Analysis.” Federal Trade Commission (1988): 97.

Simpson, James B. “State Certificate-of-Need Programs: The Current Status.” American Journal of Public Health 75. No. 10 (October 1985): 1225–29.

Smith, Pamela C. and Kelly Noe. “Is the Community Health Needs Assessment Replacing the Certificate of Need?” Journal of Health Care Finance 42. No. 2 (Fall 2015).

Stagg, Brian C. et al. “Trends in Use of Ambulatory Surgery Centers for Cataract Surgery in the United States, 2001–2014.” JAMA Ophthalmology 136. No. 1 (January 2018): 53–60.

“States Are Suspending Certificate of Need Laws in the Wake of COVID-19 but the Damage Might Already Be Done.” Pacific Legal Foundation (blog). March 31, 2020.

Stratmann et al. “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States.” Mercatus Center at George Mason University. August 29, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2020. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/corporate-welfare/certificate-need-laws-how-con-laws-affect-spending-access-and-quality.

Stratmann, Thomas and Christopher Koopman. “Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care: Certificate-of-Need Laws, Ambulatory Surgical Centers, and Community Hospitals” (Mercatus Working Paper. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. February 2016).

Stratmann, Thomas and David Wille. “Certificate-of-Need Laws and Hospital Quality” (Mercatus Working Paper. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. September 2016).

Stratmann, Thomas and Matthew C. Baker. “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry? How They Affect Access to MRI, CT, and Pet Scans” (Mercatus Working Paper. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. January 2016).

Stratmann, Thomas et al. “Certificate-of-Need Laws: How CON Laws Affect Spending, Access, and Quality across the States.” Mercatus Center at George Mason University. August 29, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2020. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/corporate-welfare/certificate-need-laws-how-conlaws-affect-spending-access-and-quality.

“Total Knee Replacement.” OrthoInfo (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons). Accessed July 27, 2020. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement/.

Whitney, Andrew. “Georgia Pares Back CON Laws.” Heartland Institute. May 31, 2019.

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy