Everyone wants jobs, and with a low-carbon energy transition underway, they especially want energy jobs. Joe Biden ran for president on a plan to create 10 million clean energy jobs. Now that he is president, his signature infrastructure proposal, which calls for $100 billion of spending on energy infrastructure, is called the American Jobs Plan.

It’s not just the president. Congress wants energy jobs. Governors want energy jobs. Many advocates, even if they do not care about energy jobs per se, emphasize employment because they believe that is the only way they can get politicians to care about the energy transition.

The mania for energy jobs brings to mind a well-known story about Milton Friedman’s visit to China. In Alex Tabarrok’s telling it goes like this:

Milton Friedman was once visiting China when he was shocked to see that, instead of modern tractors and earth movers, thousands of workers were toiling away building a canal with shovels. He asked his host, a government bureaucrat, why more machines weren’t being used. The bureaucrat replied, “You don’t understand. This is a jobs program.” To which Milton responded, “Oh, I thought you were trying to build a canal. If it’s jobs you want, you should give these workers spoons, not shovels!”

The lesson of the story is an iron truth: if you want rapid progress on an outcome, you need high output per worker. If you want jobs, low output per worker is fine. We can always spend more money and create more jobs, but those jobs come at the expense of progress on our goals.

Imagine if, by some miracle, dirt cheap 1¢/kWh clean energy suddenly became available for the taking anywhere on the planet, in any quantity, out of thin air. There would be no more energy jobs, no more energy companies, no more energy infrastructure. Would it be a bad thing?

It would certainly be disruptive. Overnight, everyone who works in the energy industry would be out of work. There’s no denying that suddenly unemployed workers would experience anxiety, fear, and short-term material hardship. They would have to find new careers and learn new skills.

At the same time, the world economy would flourish. Climate change would be all but solved. Capital that would have had to be used to build and maintain energy infrastructure could be freed up to do new things. New opportunities enabled by the arrival of cheap energy would abound. With energy abundance, we could desalinate large amounts of water and move it around the country, solving water shortages. We could cost-effectively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

We could expand production and use of energy-intensive materials — Iceland has leveraged its cheap geothermal and hydroelectric resources to become the top per-capita producer of aluminum (yes, “stealing American jobs”). What physical structures might we build if exotic materials were cheaply available? What would a genius in the mold of Buckminster Fuller build? Science fiction writer Neal Stephenson has a short story about a 20-km, actively-stabilized tower extending above the clouds and into the darkness beyond. With cheap and abundant energy, even the sky may not be the limit.

What could agriculture look like with such cheap energy? Farming has been done outdoors since the dawn of civilization, mainly because it is otherwise difficult to capture the energy plants need to grow. But we could use much less land if energy were no obstacle by growing plants indoors. Greenhouses need heat, and indoor vertical farms need electricity to run lights and water pumps. If the costs were low enough, we could grow mangos in Maine in the winter. Globally, food shortages (to say nothing of energy shortages directly) are a root cause of war. Cheap and abundant energy could mean not only better nutrition but also fewer lives lost to conflict.

Cheap and abundant clean energy would revolutionize transportation. We could travel faster, farther, and more often. We could commute across town in flying cars and jet packs, or across oceans in hypersonic aircraft. With better travel technologies, we could better maintain our long-distance friendships. Imagine going to Tokyo for lunch to catch up with an old friend. If the cost and availability of energy were no object, you could.

If the miraculous energy source suddenly appeared, it would create new jobs in downstream industries, but even this is not the point. Ideally, further miracles would abolish those jobs, too. Jobs slow the economy down. Our living standards go up when we don’t have to pay anyone to do anything. Nirvana occurs when technology itself provides all our needs, and when no human is required to work unless he or she really wants to.

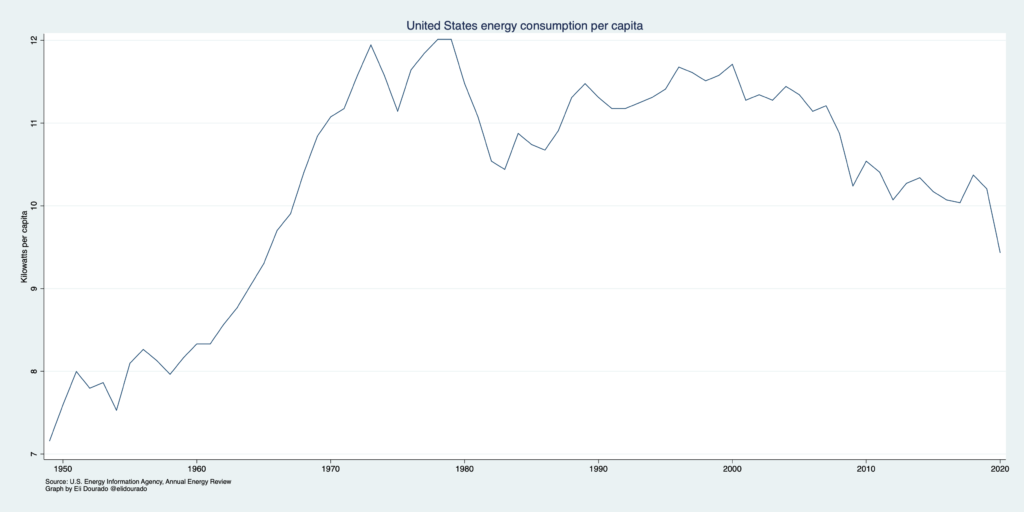

Instead of job creation, we should look to other metrics of success for the energy transition. One is how much energy we consume per person. J. Storrs Hall noted in his book Where’s My Flying Car? that American energy use per capita increased about 2 percent per year from around 1800 to the late 1970s. Since then it has fallen. We will know we have turned a corner on energy abundance when we are able to consume more than ever before.

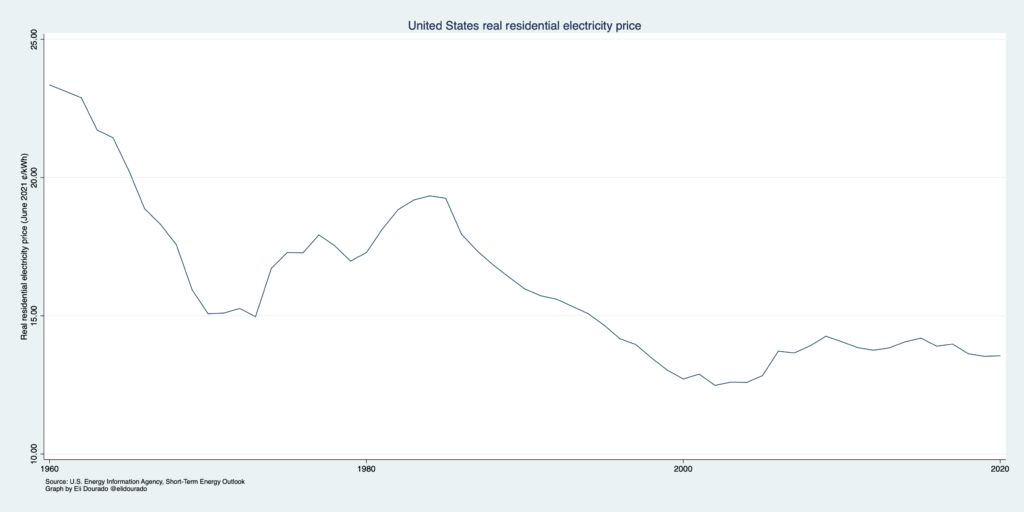

Another key metric to watch is the residential electricity price. This doesn’t tell the whole story, because we can differentiate between electricity and primary energy, and because residential electricity is more expensive than industrial electricity. But it is notable that while real residential electricity prices fell precipitously in the 1960s and the 1990s, they have gone up since 2000, averaging 13.5¢/kWh last year. How low can we push this number down?

Politicians are right that the clean energy transition represents an economic opportunity. Not only can we reduce greenhouse gas emissions and address the biggest component of climate change, our economy can thrive while doing it. The biggest obstacle to that success is a make-work mindset. We could create millions of jobs if we paid people to generate electricity pedaling on stationary bikes, the modern version of an army of spoon-wielding canal diggers. But we would be wise to instead aim for abundance and low prices — and as few energy workers as necessary.

American Enterprise Institute

American Enterprise Institute