Pointing to an ad offering “express entry” to Canada, immigration reform advocate Anirban Das joked that Canada is depleting the US workforce.

Canada wants to attract high skilled immigrants but it can always use America's broken #immigration system as an ad punch line. pic.twitter.com/ix0NOu3KYi

— Anirban Das (@anirb_das) August 30, 2021

Das’s tweet tells a comical, albeit true tale. The United States is competing with other countries for skilled workers and struggling to keep up. Das is right, the US system is the unfortunately unfunny punchline. For example, the Canada Express Entry program referenced by Das had a 75 percent increase in the number of US residents applying between 2019 and 2020, due to a surge in non-citizen submissions. In short, Silicon Valley hopefuls are leaving for more certainty about their immigration status. Countries like Canada have their arms wide open, ready to receive.

These competitions for skilled workers will only continue to escalate. Portugal, for example, has a program to entice workers into the country with benefits like a zero percent tax rate on foreign income and even noting that they have a high English fluency rate. A variety of these kinds of “digital nomad” visas exist now. After all, who remembers the last week that lacked some form of a Zoom call?

To get serious about the competition for global talent, the United States needs to expand the avenues allowing skilled immigrants into the country. One of the best ways currently available in the US is for universities to establish a Global Entrepreneur in Residence (GEIR) program. These programs take advantage of existing immigration laws to give skilled immigrants willing to mentor college students a streamlined pathway into the US. GEIR programs capitalize on the university’s role as a way to grow local economies and can be one step towards ensuring the US’s long-term success.

The Parable of Ori Living

A trio of MIT engineering students, Hasier, Ivan and Chad, came up with an idea for robotic furniture in their company Ori Living. They developed and presented their ideas to potential investors and clients who offered them $750,000 in company start-up funds in November. To remain part of the founding team after graduation, Ivan had to secure an H-1B visa. Ivan would have had to wait for the H-1B lottery which wouldn’t take place until April and with the visas not being issued until the next October.

Even if Ivan pursued the H-1B visa, there was no guarantee that he would get one in the lottery system. This uncertainty likely deters potential immigrants from even applying to work in the United States. There are many obstacles that H-1B applicants face, particularly for entrepreneurs.

Instead of waiting for the H-1B lottery, Ivan turned to the University of Massachusetts’ Global Entrepreneur in Residence (GEIR) program since universities are exempt from the H-1B caps and can file for a visa at any time. Through a GEIR program, foreign entrepreneurs can work as a university employee while developing their startup.

So the founders moved Ori Living to the Venture Development Center (VDC) at the University of Massachusetts and immediately filed an H-1B petition for Ivan through the university. It was granted and allowed Ivan to stay and work on Ori while he waited for an H1-B visa independent of the university. He applied for his independent visa in April of the following year, and it was granted in September. Ori Systems then “graduated” and moved on from the Development Center, where after one year they received $6 million more in funding.

U.S. Universities should 10x their GEIR programs

As illustrated by Ori Living’s success, GEIR programs are already creating a better pipeline for skilled labor into the country. Yet, there are only seven active participating schools in the United States out of 2,500 possible opportunities at 4-year universities today.

This lacking uptake is despite the success of GEIR programs so far. Since 2014, 80 UMASS foreign entrepreneurs have raised over $1 billion in project funding, creating over 1,600 jobs in the United States. In just seven years, the UMASS VDC has changed the lives of 1,600 families in the Boston area by extracting skilled labor from an under-utilized pool of applicants.

By expanding the number of GEIR programs, more universities can create the successes seen at UMASS for themselves. This fits well with the role that universities already play. Universities stimulate economic growth in the communities they fit into. Recent research shows that increased federal research commitments are positively correlated with the quantity of entrepreneurship. That is, university research translates into greater startup activity. The benefits from research spillover into the local area. They don’t just represent books and studies that sit in the university library. They create new opportunities for the community.

Combining research funding with additional skilled immigrant labor can make universities a powerhouse for new economic opportunity. The ideas that they contribute to in their education can be turned into operating businesses with the addition of a GEIR program.

Of course, jumping overnight from seven programs to 2,500 would be difficult to impossible. Yet state policymakers and university administrations should begin the establishment of at least 100 GEIR programs today.

GEIR programs can be started by any university willing to put a system in place. The federal government can help by making it clear to university officials how to follow the H-1B cap exemption rules. But there’s no reason to wait for Washington DC to get involved. A GEIR program only requires a dedicated university administration willing to grab the opportunity.

How to Set Up a GEIR Program

A key advantage of the GEIR route is that today’s immigration rules allow the establishment of a GEIR. Universities don’t have to apply to a program or get permission from any government agencies. The only people who can say ‘no’ are the university officials who choose not to create one at their university. Unlike other immigration reforms, this one doesn’t depend on what lawmakers do in Washington DC. It’s something that universities can and should do today.

Universities are already cap-exempt from the H-1B lottery. In addition, administrators and staff likely have experience and understanding of the H-1B process already because many universities hire professors with H-1B visas. The GEIR program is using that infrastructure to bring additional people into the university.

In many cases, GEIR programs are based in a university’s business school. Given their goals of incubating successful businesses and providing mentorship to students interested in starting a business, this makes sense. But it’s not a legal requirement. For example, Babson College was the first private college to establish a GEIR program.

The University of Massachusetts, Boston’s VDC is a concrete example of the infrastructure that other universities can pull from. They provide several services for students looking to start a company, as many universities do—the GEIR is just one of them. It is a tool that could be grafted into any existing business development program.

GEIR requires that the accepted entrepreneurs make a service commitment to the local community. Sometimes they complete this requirement through formal pledges, like Pledge 1%, which requires a donation of 1 percent of the entrepreneur’s time, profits, equity or product. But it can be done anywhere by having the H-1B recipients serve as mentors to university students. Not to mention that many of the participants in GEIR programs will hire university students and create job opportunities for nonstudents as well.

The legal parameters are in place, entrepreneurs are waiting in the wings. Universities: in the words of the modern sage Shia Lebouf, “just do it!” GEIR programs are a promising way that the US can better compete for skilled workers and meet the growing demand for those workers.

Why the U.S. Needs More GEIR Programs

The United States needs a better pipeline to realize the benefits of immigration. The current system is holding employers back and allows other countries to poach the talent that we educate or train. A promising way forward is to make immigrating easier by expanding the pipeline into the country with Global Entrepreneurship in Residence programs.

It’s no mystery that the United States is experiencing a skilled labor shortage. As the labor force continues to age and population growth is on a downward trend, the American economic powerhouse is set to contract over the coming decade. Specifically, the STEM market has a projected shortage of about 1 million professionals in the coming decade, should the United States continue its trending growth in science and technology.

Meanwhile, immigrant workers in STEM are flocking to more secure visa opportunities like those created by Canada and Australia. PhD STEM workers from abroad can also apply for EB-2 visas (or “exceptional ability” green cards), of which the United States offers 40,040 per year. Yet, no single country’s people can receive more than 25,620 EB-2 visas. China and India have exceeded this quota in number of applications for the past 16 years and are facing longer and longer delays in the EB-2 program. There is a large supply of skilled labor that wants to fill our shortage, but we limit options by adding such a low ceiling.

On top of a declining supply of labor, the United States has effectively cut H-1B visas by two-thirds since 1990. Because the US economy has more than tripled since the 90s, the number of H-1B visas has shrunk relative to the size of the economy. As the economy grows, the labor market grows hungrier and hungrier for skilled workers.

This stagnation is particularly a problem for the tech industry which both relies on H-1B workers more than others and has seen an even greater expansion than the general economy in the last 30 years. Failing to expand visa programs has kept the immigration system in the days of cassette tapes and CDs rather than keeping pace with new services like Netflix and Spotify.

Expanding skilled immigration will also benefit natives everywhere. Studies have shown that foreign-born workers have higher rates of entrepreneurship, boost patenting in technologies their home country specializes in, and on average raise real wages of college-educated natives. One analysis of cutting H-1B numbers showed that restricting the program harms less-educated natives. Exactly because immigrants are likely to create new businesses and products, they improve the lives of all natives--including the less educated who don’t work in technology or STEM fields.

Outside of academic research, pause and consider how Google searching has taken over the world, how Amazon dominates e-commerce, and how Apple has revolutionized the smartphone. Each of these companies were started or managed by first and second generation immigrants. Immigration makes natives better off--and these are three concrete examples. These aren’t outliers either. First or second generation immigrants are also responsible for founding about 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies.

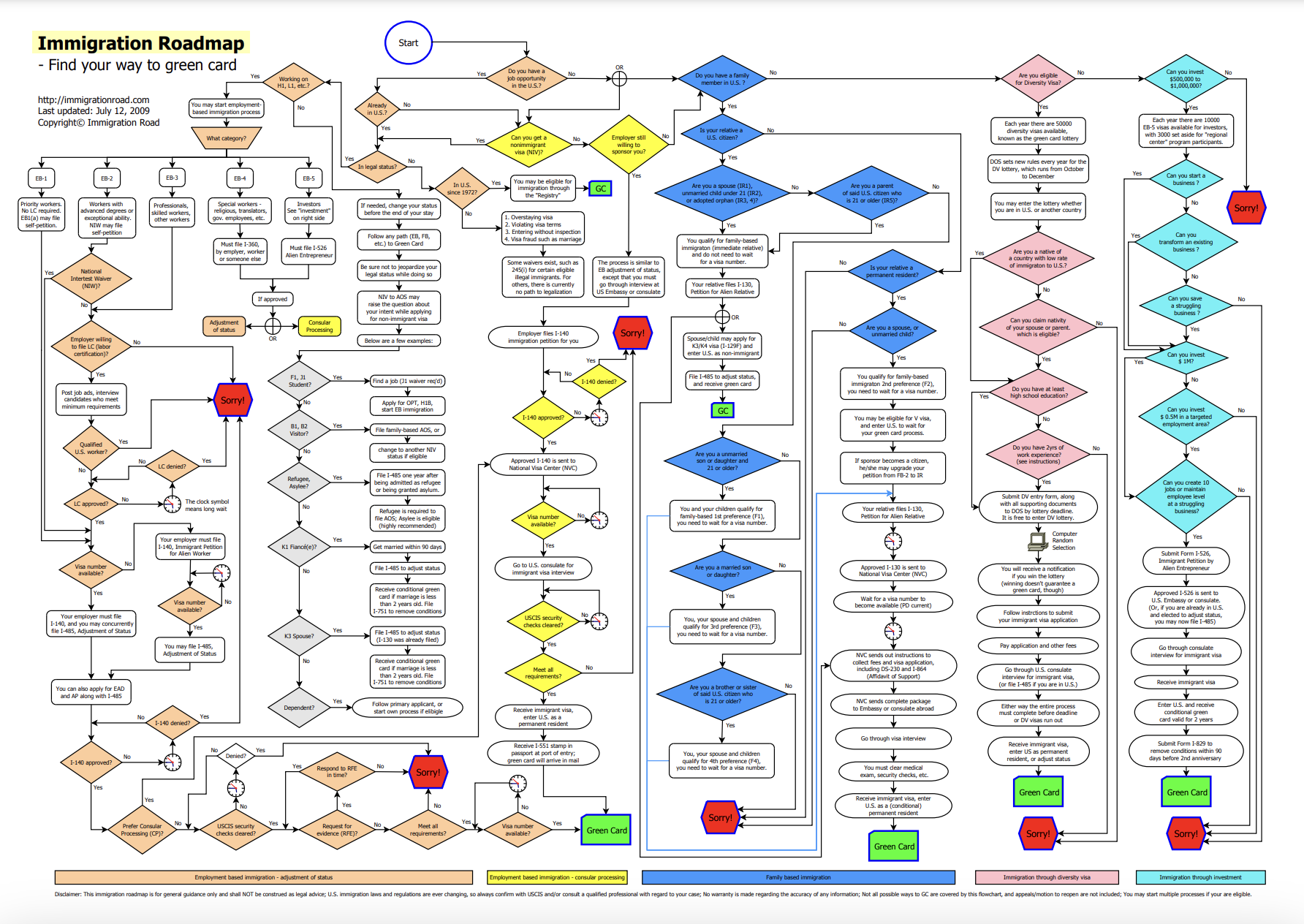

And yet, the process to receive a visa can be even more complicated than it was for Ivan of Ori Living. Immigrants are pulled through an arduous web of tasks and requirements similar to the Immigration Roadmap below.

Source: Immigration Road.

In other cases where participants don’t win the H-1B lottery, these global entrepreneurs are limited in their ability to remain in the United States. In order to petition for an O-1 (extraordinary persons) visa, the applicant must be of significant stature in their field of study which is subjective and difficult to estimate.

There is also no direct path to achieving an EB-2 visa without an advanced United States degree and five years experience. An individual must also demonstrate a “degree of expertise significantly above that ordinarily encountered in the sciences, arts, or business”, but there is no clear measurement of this factor. How do immigrants know where they could meet this requirement, let alone be one of the lucky few that are chosen? The H-1B visa is the pathway to either an O-1 or EB-2, but they typically take time and are capped outside of universities.

Our failing skilled immigration system excludes thousands of skilled workers from working in the United States to our country’s detriment and the gains of other countries.

GEIR Programs are a Solution Ready for Prime Time

As the stagnation evident in Canada’s increased poaching of US-based talent, our failure to raise the H-1B visa limits, and our complex immigration system reveals, the US needs to get serious about competing for people.

Universities in Colorado, Missouri, Alaska, and San Jose State are already running GEIR programs. These initiatives offer countless financial incentives for the universities involved and their surrounding communities. Though decision makers in the federal government should be looking to expand a number of pathways for skilled workers, there’s room today for universities to step up and begin growing the economic pie for all by creating their own GEIR programs.

Adding a GEIR program is simple. All universities need to do is reach out and take another opportunity to bring prosperity to their communities.