As the United States debates how to deal with the refugees created by its withdrawal from Afghanistan, a central concern is how bringing them to the country might affect public safety.

The practical trade-off is clear: speed for certainty. A timeline that U.S. intelligence analysts had estimated at weeks compressed into days as Kabul fell. There is little time to find avenues for those who helped U.S. forces into the U.S. or at least out of harm’s way as the Taliban solidifies its control over Afghanistan and its capital. The existing programs, whether traditional refugee systems or special programs for U.S. allies, have been slow to process paperwork and send approvals.

Those U.S. allies left behind in Afghanistan don’t really have the time for the bureaucratic delays to work themselves out. As Ryan Crocker, the former ambassador to Afghanistan, concluded his June 2021 congressional testimony on the need to clear pathways for Afghan allies to the U.S., “Now it is very late in the day, but perhaps not too late for this Administration to follow the lead of the American people, and ensure our national honor is not left behind with those who risked their lives for us.”

The policy relevant question is what evidence is there that refugees or immigrants from Afghanistan are likely to be public safety threats? That is, should the presumption be guilty or innocent? The long body of research on immigration provides a clear answer. The American way of innocent until proven guilty is better suited for today’s Afghanistan-refugee challenge.

Do refugees cause crime?

The relationship between immigration and crime has spilled books worth of ink many times over. That’s despite the unexciting conclusion: immigrants are usually less prone to crime than are similar natives. In news coverage of immigration, however, the tantalizing outliers make better stories than do the doldrums of the average story.

The central finding from immigration researchers is that immigrants are not public safety threats. In their review of the evidence, economists Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny conclude, “A crucial fact seems to have been forgotten by some policymakers as they have ramped up immigration enforcement during the past two decades: Immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than similar US natives.”

Despite this, researchers also find that the relatively rare immigrant criminal is disproportionately the subject of media attention. One analysis of 2,200 stories in national newspapers concluded that immigrants are often described as crime-prone. This is despite the well-established statistical evidence against exactly this description.

In another well-known 2018 study, political scientists Emily Farris and Heather Silber Mohamed demonstrate that the media tends to portray immigrants as criminals and threats. Like the other analysis, they examine pictures of immigrants in media stories. Media organizations choose pictures that emphasize threats and immigration enforcement efforts rather than other elements of the immigrant experience.

Both of these studies reflect an old media saying, if it bleeds, it leads. Rather than emphasize the averages, media outlets tend towards focusing on the gory and the shocking because it draws eyes. These representations, however, make for weak support for restricting immigration in practice.

There is unfortunately little on the specific relationship between Afghan refugees and crime rates. Yet, what exists sometimes reflects the same bias of the media towards the negative. For example, a 2017 essay in the foreign policy-focused magazine, The National Interest, claims that Afghans are prone to criminality, especially sexual crimes. These are serious accusations that deserve full investigations in every case. Yet there’s no reference to statistics on crimes by Afghans. The power of this claim comes from the horrific stories of violence rather than from the weight of evidence behind it.

Specific data on Afghan immigrants to the U.S. paints a different picture–one that is much more optimistic. U.S. natives are 11.6 times more likely to be incarcerated than Afghan immigrants. Though it’s unlikely to matter in effect, this number is for Afghan immigrants as a whole, not just Afghan refugees.

Zooming back out to studies of refugee resettlement in the U.S. gives more reason for optimism. Research is clear that refugees do not pose a safety threat to the United States.

The clearest evaluation of the relationship between refugee resettlement and crime in the United States is a 2020 study by three economists. The study uses data from 2007 to 2014 on where refugees were resettled in the U.S. and compares that data to crime rates in the resettlement areas. The study concludes that there is no relationship between crime and refugee resettlement.

A second study explores if refugee reductions caused by the travel ban in President Trump’s Executive Order 13769 affected crime rates in the country. Although that order did not include Afghanistan, it applied to seven Middle Eastern countries, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. Despite a 66 percent reduction in refugees, the study concludes, there was no significant effect on crime rates.

The research is clear: the U.S. refugee resettlement system as a whole does not jeopardize public safety. In addition, there’s no statistical evidence that we should hold special concerns about safety threats from Afghan refugees. However, Europe has had a slightly different experience. In a few cases, researchers have documented cases where refugee resettlement increased crime or imported terrorism. Should U.S. policymakers worry about this research?

When can refugees cause crime or spread terrorism? And why the U.S. shouldn’t worry

There’s a long list of reasons why U.S. refugee policies differ from international policies. This means that research on refugee policies between the U.S. and Europe aren’t necessarily good comparisons. Importantly, the researchers who do find some evidence that crime or terrorism increases because of refugee resettlement, also note that their findings are unlikely to apply to countries like the United States.

A major difference is the relative size of the U.S. compared to European countries. The U.S. is much larger geographically and by population than European countries. Utah alone, for example, is more than twice the geographic size of Hungary while holding only a third of the population. In addition, the U.S. has a stronger cultural history of immigrant integration than do many European states. The American myth is bound up in the promise of America to immigrants.

Another reason is that the U.S. resettles refugees at a shockingly lower per capita rate than other countries. So we have a lot of room to resettle when thinking about either demographics or geographics. Pew Research Center data shows that, per million residents, the U.S. takes in about 70 refugees compared to Canada’s 756, Australia’s 510, and Sweden’s 493. Even taking in an additional 50,000 (or more!) Afghan refugees would not meaningfully affect these international comparisons. That gives the U.S. a lot of room to take in more before it’s likely to run into similar problems, in the unlikely case that it would at all.

The U.S. also has much stronger institutions than do many countries taking in refugees. Institutions loom large in the few studies showing that refugees can import terrorism or crime. One illustration is found in how U.S. refugee policy encourages refugees to become self-sufficient. In the U.S., refugees are immediately eligible to work. In Europe, however, that is not always the case. A foundational study of refugee arrivals in Europe suggested that when refugees are not able to work, they can turn to crime as a way to bring in income. In contrast, when refugees can work, there is no increase in crime rates. The U.S. practice of encouraging refugees to economically assimilate by finding work may explain some of its success with refugee integration.

The environments that refugees enter also matter. A 2016 study showed that migration can diffuse terrorism from one country to another if discrimination against the migrants creates fertile ground for terrorist groups to spread their influence. The relationship is complicated. But it’s clear that there is no necessary connection between migration and terrorism. As the authors point out, their analysis showed that more migration was associated with a lower level of terrorist attacks.

More relevant to the U.S. given its strong institutions are findings that resettlement is only likely to result in political violence in weaker countries. Established countries, like the U.S., are unlikely to see security risks from refugees because they have the capacity to care for migrants. Which is evident in the studies examining U.S. refugee admissions and public safety.

What can the U.S. do to help Afghans?

Given that there is no reason to fear immigration from Afghanistan, the U.S. is in the enviable position of having several options for responding to the needs of Afghan allies. There are existing special immigration programs for those who aid U.S. military forces and both the U.S. refugee system and the Temporary Protected Status program provide potential pathways for Afghans to come to the U.S. legally and safely.

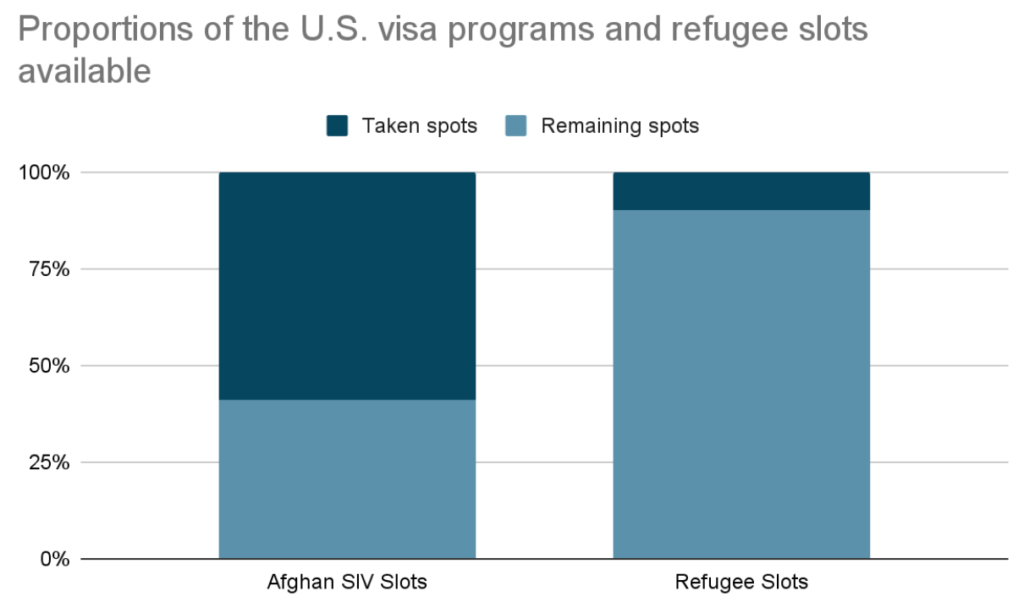

The Special Immigrant Visa Program for Afghan created 26,500 visas for those who were employed by the U.S. military. In January 2021, there were almost 15,000 applications for the program. There are also similar programs for Iraq. Reporting varies depending on which SIV program is being discussed and if reporting is combining them, but it appears that there are around 50,000 Afghans who would qualify for at least one of the SIV programs and 34,500 slots remaining, according to Roll Call.

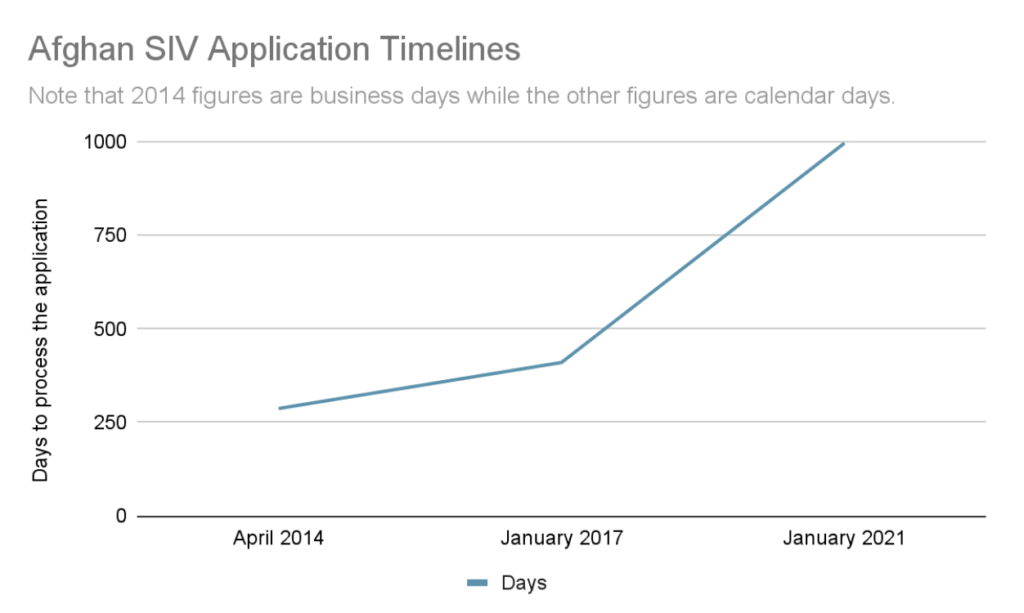

There are two challenges for the SIV program. First, the remaining number of spots in SIV are dwindling. Only 10,859 spots remain in the Afghan program, according to the State Department and Department of Homeland Security’s April 2021 report. Second, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) has pointed out that the timeline for the programs is long. As early as 2010, the program was criticized for being impossible to navigate without an English-speaking legal aid. Despite reforms since these critiques, the CRS reports that the Afghan program requires 996 calendar days as of January 2021. Those times are trending in the wrong direction as well–in 2017 it only took 410 days. Applications for the SIV program should be done at a sliver of the current time.

The CRS report on SIVs attributes these skyrocketing timelines to low program staffing paired with a large number of applications. The Department of State in May told reporters that it was devoting more resources to the application processing, though it is not clear that it succeeded based on anecdotes from those applying from Afghanistan.

Streamlining these applications should be a priority for the administration, but so should alternative pathways. One option is to bring Afghans to the U.S. through the normal refugee program. Refugee resettlement is done by fiscal year. Fiscal year 2021 had a total of 62,500 spots available. As of the end of July, the Biden administration has resettled only 6,246. That leaves 56,254 spots open in the refugee program that expire on October 1 when FY2022 begins.

Another potential tool to consider is Temporary Protected Status (TPS). The TPS program allows the Department of Homeland Security to designate a foreign country for protection if the country’s nationals would be unsafe if they returned or stayed in their home country. One of the conditions included within TPS authority is armed conflict as well as other extraordinary conditions, which makes Afghanistan a clear candidate.

In every case, it’s possible to include a simple background check through fingerprinting or facial recognition. There are existing databases within the Department of Homeland Security that applicants could be processed through. Using biometrics to screen applicants can be the first step if there are informed causes for concern. Further screening can be done within the country as needed. The U.S. should embrace its presumption of innocence, to borrow an idea from the justice system, rather than require what amounts to 2.7 years of processing time for the Afghan SIV program. The Office of Biometric Identity Management within DHS claims to have stopped thousands of ineligible travelers from entering the country. Applying these same systems to refugees can screen out those who pose security threats.

Living up to our obligations

In any of these cases, the U.S. will need to move quickly. We have the blessing of multiple options, but we do not have the luxury to delay. The research on refugees, crime, and terrorism make it clear that there is no serious public safety threat from opening our arms to the people of Afghanistan.

Our obligations are especially clear to those who aided the U.S. military, at great risk to themselves. Many Afghans were, as the Taliban called them, the eyes and ears of the American military. Because of that, the Taliban also commonly said, “Shoot the eyes first.” There is no reason to believe that their thinking will change as they establish themselves in the country.

The Deseret News in Utah shared the experiences of several Afghan allies as the Taliban advanced and took over. Each interpreter and construction worker interviewed shares their harrowing situation. Abidullah, who passed both interviews required to qualify for the Afghan SIV but will likely not receive the visa now that the embassy is closed, makes an especially depressing conclusion to the reporting:

We will die. This is our future now. We can’t do anything. We can’t reach Kabul in safety. What should we do? They (the U.S.) never think about our future, our family. They forgot our struggles and everything that we have done for them. Why are they doing this? I am extremely disappointed.

With the number of policy options available to us, it doesn’t have to be this way. With the political will, the Afghan allies can find protection here.