Since the 1990s, American public opinion has become considerably more favorable towards immigration. In 1993, only 6% said that immigration should be increased, and 65% said that it should be decreased. By 2016, support for an increase had risen to 21%, and support for a decrease had fallen to 38% (Gallup 2023).1Support for higher levels of immigration has generally continued to increase—the latest survey (July 2022) found 27% in favor of an increase, 38% in favor of a decrease, and 38% in favor of keeping immigration at its current level. In 1994, in response to a CBS News/New York Times question asking whether “most recent immigrants to the United States contribute to this country or do most of them cause problems,” 29% said that they contributed, and 53% that they caused problems. By 2015, the percentages had reversed with 59% saying that most contributed, and 28% saying they caused problems (CBS News 2015).

Despite this shift in public opinion, in 2016, Donald Trump won the Republican nomination and then the presidency with a campaign that featured opposition to immigration as its central theme. Trump was able to use the immigration issue to his benefit by focusing on illegal immigration. He claimed that illegal immigration was a crisis—that people were “pouring” across an unprotected border, bringing crime, drugs, and other social problems—and that neither Democratic nor Republican leaders had attempted to control it. Thus, the issue was central to his image as a populist who represented ordinary people against the “elites.”

Some observers who were not Trump supporters shared his general view of the difference between popular and elite opinion. Peggy Noonan (2016) wrote, “If you are an unprotected American—one with limited resources and negligible access to power—you have absorbed some lessons from the past 20 years’ experience of illegal immigration. You know the Democrats won’t protect you and the Republicans won’t help you. Both parties refused to control the border.” Ross Douthat (2019) spoke of “a gap between the elite consensus on immigration—unabashedly in favor—and the public’s more conflicted attitudes… Across the first 15 years of the 21st century, too many Beltway attempts to simply impose the elite consensus set the stage for backlash, populism, Trump.”

There are several reasons a hard line against illegal immigration can have strong popular appeal, even among people who have positive views of legal immigration. First, people may simply object in principle to violation of the law. Wright, Levy, and Citrin (2016, 230) find that, in many cases, negative judgments about illegal immigrants reflect “rigid moralistic convictions about the importance of strict adherence to rules and laws.” Second, people may regard illegal immigration as unfair to would-be immigrants who are “playing by the rules” and applying for legal admission. Finally, even if people sympathize with illegal immigrants as individuals, widespread violation of the law may lead them to feel that the government is not in control. Trump frequently appealed to a diffuse sense of fear and uncertainty: in the speech announcing his candidacy, he said that illegal immigration is “coming from all over South and Latin America, and it’s coming probably—probably—from the Middle East. But we don’t know. Because we have no protection and we have no competence, we don’t know what’s happening” (Trump 2015).

This paper examines elite and popular views of illegal immigration using a series of surveys conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs (CCGA—formerly the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations). Although there are many surveys of public opinion, surveys of elites are scarce, so most claims about elite opinion are based on impressions rather than systematic evidence. The CCGA has conducted parallel surveys of both elites and the general public, and some of the questions have been repeated over long periods of time, making the data a valuable source for examining differences between elite and public opinion.

A limitation of the CCGA data is that only one question on illegal immigration has been regularly included. This question is part of a series in which respondents are offered various objectives and asked if each one should be a “very important foreign policy goal, a somewhat important foreign policy goal, or not an important goal at all.” One of the potential goals is “controlling and reducing illegal immigration,” (Chicago Council on Global Affairs 2023a, 2023b). Although it would be desirable to have additional questions on illegal immigration and proposals about how to respond to it, the priority question measures an important underlying attitude. To a large extent, illegal immigration is what Stokes (1963, 373) called a “valence issue:” one in which party competition involves “linking of the parties with some condition that is valued positively or negatively by the electorate.” Illegal immigration is almost universally regarded as undesirable in principle: even the strongest supporters of increasing immigration want to accomplish their goal by changing the laws rather than by non-enforcement.2Between 2006 and 2011, nine CNN surveys asked “Would you like to see the number of illegal immigrants currently in this country increased, decreased, or remain the same?” Support for an increased number averaged about 4%, while 70% to 75% said that they would like to see the number decreased (CNN 2011).

However, there is uncertainty about how harmful illegal immigration is in practice, how much it could be reduced by stricter enforcement, and the extent to which stricter enforcement would have undesirable consequences, such as increased surveillance of American citizens. Answers to the CCGA question can be regarded as a summary of the perceived costs of accepting some level of illegal immigration relative to introducing “get tough” policies. Views on this underlying issue will influence views on specific proposals. Evidence of this connection can be seen in the 2016 surveys, which included some additional questions on policy towards illegal immigrants in the United States (CCGA 2023a, 2023b).

In the general public, of the people who said that controlling and reducing illegal immigration should be a very important foreign policy goal, 46% said that illegal immigrants currently working in the United States should be required to “leave their jobs and leave the country.” Only 10% of those who said it should not be an important foreign policy goal took this position. Among elites, there was also a strong connection: 10% of those who rated controlling and reducing illegal immigration as very important and only 1% of those who said it was not important were in favor of requiring illegal immigrants to leave the country. Opinions on the importance of controlling and reducing illegal immigration were also strongly connected to support for building a wall along the Mexican border.3This question was asked only in the survey of the public.

This paper will use the CCGA data to consider three questions about differences between elite and popular opinions. The first is simply whether there is a difference between the priority that elites and the general public give to “controlling and reducing illegal immigration.” The second is whether there is an “elite consensus,” as suggested by Noonan (2016) and Douthat (2019), or divisions of opinion within the elite, particularly partisan divisions. The third is whether elites and the public differ in terms of the associations between the priorities they give to illegal immigration and other goals: that is, whether there is a difference in the structure of elite and popular thinking. The next section will discuss the reasons that there might be differences between elite and popular opinions, as well as relevant research on these points.

Research Questions

The general concern of this paper is the difference between elite opinions and general public opinions about illegal immigration. Elites can be defined as people with the power to make or influence decisions in the major institutions of society (more detail on the composition of the elite samples in the CCGA surveys will be given in the next section). The first question to be considered is whether there is a difference between average opinions of elites and the public.

The literature offers several reasons opinions may differ between these groups. One possibility is that there are demographic differences between elites and the public: elites are more educated and affluent than the average person, and also more likely to be white, male, and older. Kertzer (2022) examined a large number of questions from the CCGA data and found that about 30% of the gap between public and elite opinions could be accounted for by demographic differences. Another possible reason is a difference in knowledge and information. Elites usually have in-depth knowledge of certain issues that goes well beyond that of even a well-informed citizen. Moreover, even if they do not have detailed knowledge of a topic, they can call on experts for information and advice and therefore are likely to be influenced by expert opinion.

Differences in general values and principles may also account for the disparity of opinions. Members of elite groups tend to have a stronger and more consistent commitment to the prevailing values of a society. For example, Stouffer (1955) found that support for civil liberties for unpopular groups was higher among elites than among the general public: both elites and the public strongly endorsed the principles of “free speech” or “due process,” but elites applied those principles more consistently. This was partly due to differences in educational level, but a gap remained between even the educated public and elites. Freeman (1995, 909) applies a similar analysis to immigration, suggesting that elites in Western societies are favorably disposed towards immigrants because of their commitment to a “social/cultural ethos” of individualism.

The second question to be considered is whether there is an elite consensus or differences of opinion among elite groups. On most issues, ideological and partisan divisions are larger among elites than among the general public (Converse 1964; McClosky 1964). This difference is partly the result of awareness—people who pay attention to politics are more familiar with the positions that are usually associated with their party or ideological group and the arguments justifying them.

However, there are also factors that may promote elite consensus on certain issues. One is personal contacts: elites work and exchange information with other elites, and consequently may develop a common outlook. A second factor is the influence of “expert” opinion: if there is a consensus among the people who are regarded as authorities on an issue, then elites of both parties are likely to adopt that consensus. These considerations are likely to apply more strongly to issues that do not get much attention from the public. On such issues, elites have more freedom to reach agreement based on what they regard as the common interest without having to consider political advantage. Finally, elites may be united by their material interests. For example, Page and Barabas (2000, 352) say that immigration “tends to put more downward pressure on the compensation of low-wage citizens than high-salary leaders.” Advocates of stricter enforcement of immigration laws often emphasize this factor: for example, Noonan (2016) writes that “many Americans suffered from illegal immigration . . . [b]ut the protected did fine—more workers at lower wages. No effect of illegal immigration was likely to hurt them personally.”

The final question is whether elites and the public differ in terms of the connection between views on the priority of illegal immigration and other issues. Converse (1964; 1971) and Zaller (1992) proposed that for most people, positions on issues follow party identification. That is, a Democrat will adopt the positions favored by leading Democratic politicians, and a Republican will adopt the positions favored by leading Republicans. Since the transmission of opinions from elites to the public is imperfect, correlations among different opinions will be smaller in the public than in elites. In effect, some voters will not be aware of what they are “supposed” to believe as Democrats or Republicans and will adopt opinions for idiosyncratic reasons. However, the pattern will be the same: the pairs of opinions that are more strongly associated among elites will be more strongly associated among the public.

Other observers, however, hold that ordinary people take a more active role in thinking about issues (Lakoff and Ferguson 2006). In this view, there are a variety of different “frames,” or ways of making connections among different issues. Differences in framing will produce differences in the correlations among opinions on different questions. There are several reasons that the prevalent frames might differ between elites and the public. One is difference in factual knowledge or beliefs. For example, one of the other potential goals offered in the CCGA surveys is “stopping the flow of illegal drugs into the United States” (Chicago Council 2023a; 2023b). Someone who believes that stopping the flow of drugs is an important priority and that illegal immigrants frequently bring drugs into the country is likely to conclude that reducing illegal immigration should also be a priority, while someone who agrees that stopping the flow of drugs is important but does not believe that illegal immigrants are a major source of drugs will not draw that conclusion. Consequently, if the belief that illegal immigrants are a major source of drugs is more prevalent in the public than among elites, the connection between the priority given to the two issues will be higher in the public than among elites.

Another potential source of differences in frames is that elites usually put more emphasis on general principles when thinking about specific issues (McClosky 1964). Illegal immigration can be thought of in terms of a conflict between an individual right to freedom of movement and a group right to decide who should be included in the community. Therefore, elite views on the priority of illegal immigration may be more strongly connected with other issues that can be thought of in terms of the balance between individual and group rights, such as “helping to bring a democratic form of government to other nations,” where the conflict is between an individual right to freedom and a national right to autonomy (Chicago Council 2023a; 2023b).

Data

The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations (now known as the Chicago Council on Global Affairs) began conducting surveys of elite and public opinion in the 1970s. A series of questions on the importance of various possible foreign policy goals was added in 1994 and continued until 2018. The list of goals changed over the years, but “controlling and reducing illegal immigration” was included regularly. Surveys of the public are available for 1994, 1998, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2018. The surveys were originally face-to-face; more recently they have been conducted over the internet, but all were designed to obtain a representative sample of the adult population.

Parallel surveys of “opinion leaders” were conducted in 1994, 1998, 2004, 2014, 2016 and 2018. The sample included “Americans in senior positions with knowledge of international affairs. . . . Leaders were drawn from the Foreign Relations, Foreign Affairs, and Armed Services committees of Congress and from international offices in the State, Treasury, Defense and other federal departments . . . the business community (international vice presidents of large corporations), the media (editors and columnists of major newspapers and magazines, television and radio news directors and network newscasters), academia (presidents and scholars from major colleges and universities), and private foreign policy institutes. A smaller number of leaders was drawn from national labor unions, churches and special interest groups relevant to foreign policy” (Chicago Council on Foreign Relations 1995).

Since there is no well-defined population of elites, it is not possible to speak of representativeness. However, the sample is wide-ranging and is limited to people with direct or indirect influence over policy, so it provides a useful measure of elite opinion. Kertzer (2022, 546) notes that “because the Chicago Council studies began in an era when political elites weren’t inundated with requests to participate in academic studies, the data here include access to unusually high-level respondents.” According to Page and Barabas (2000, 344), “These are the best (indeed the only) available data for comparing, over a long series of surveys, the policy preferences of U.S. citizens and foreign policy leaders.”

The elite sample was classified into eight groups: academic, business, Congress, executive branch, media, labor, religion, and think tanks. The surveys usually included about 400 cases, although the number varied from year to year. The earlier elite surveys included roughly equal numbers from all groups, but in recent years the group sizes became less balanced—for example, the 2016 sample included 109 academics and only seven labor leaders. To minimize the possible effects of changes in sample composition, the analyses in this paper use weights that equalize the effective sample size from each group in each year.

The central question for the analysis is a rating of the importance of “controlling and reducing illegal immigration” as a foreign policy goal. The options were “very important,” “somewhat important,” and “not important at all,” which are coded as 3, 2, 1. The complete list of potential goals is given in Appendix Table 1 (not all of the items were included in all years).

Analysis

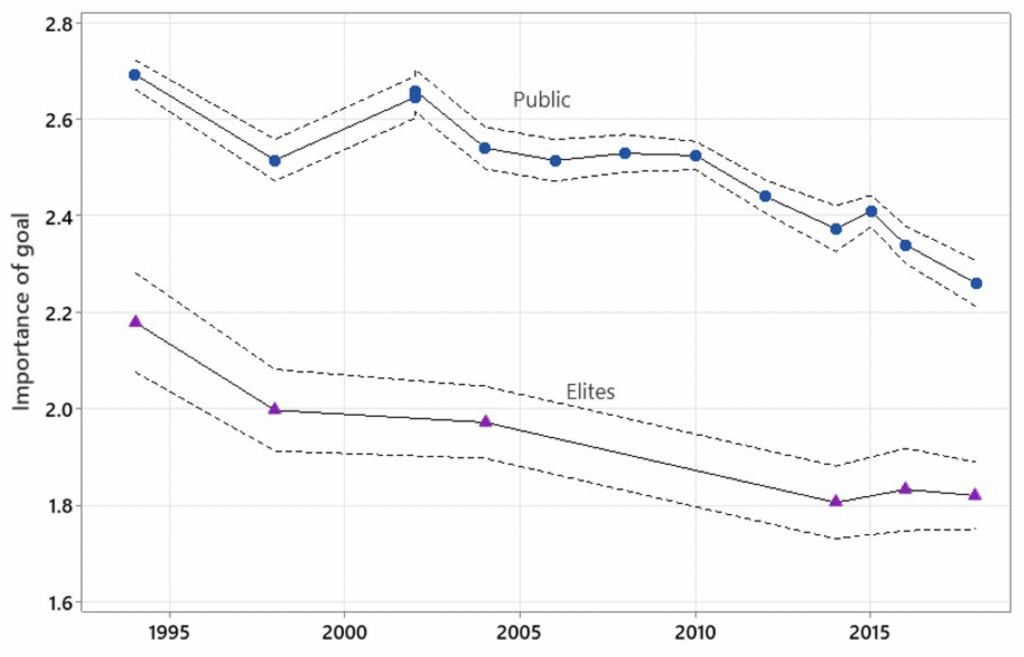

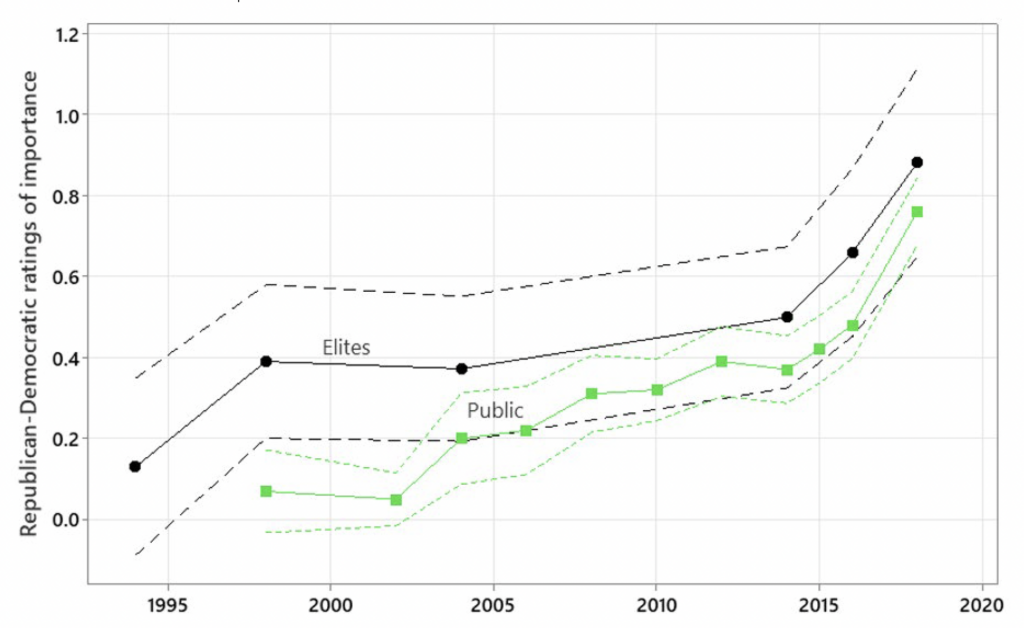

Figure 1 shows mean ratings of the importance of “controlling and reducing illegal immigration,” as well as the 95% confidence intervals for elites and the public. Two points are clear: the public consistently rates the issue as more important than elites do, and there is a downward trend among both elites and the public. There are some statistically significant year-to-year differences in the sample of the public—for example, people gave illegal immigration a lower priority in 1998 than in either 1994 or 2002. However, most of the change is a general downward trend, which became stronger after about 2010. Given the small numbers in the elite samples, there is more uncertainty about year-to-year variation and the exact shape of the trend, but there is clearly some downward movement. The estimated decline is somewhat larger among the public: when the popular and elite priorities are regressed on a time trend, the estimate is –0.0148 for the public and –0.0099 for elites, and the t-ratio for the difference is about 2.5. Consequently, the gap between public and elite opinions declined over the period, although it remained substantial even in the most recent surveys.

Figure 1. Importance of Controlling and Reducing Illegal Immigration

The difference between elite and public priorities is also visible when the goal of controlling and reducing illegal immigration is considered in relative terms. In 1994, the public rated it as the fourth most important of seventeen possible goals, while elites rated it as thirteenth. In 2016, the public rated controlling immigration eighth of thirteen possible goals, and elites rated it last.

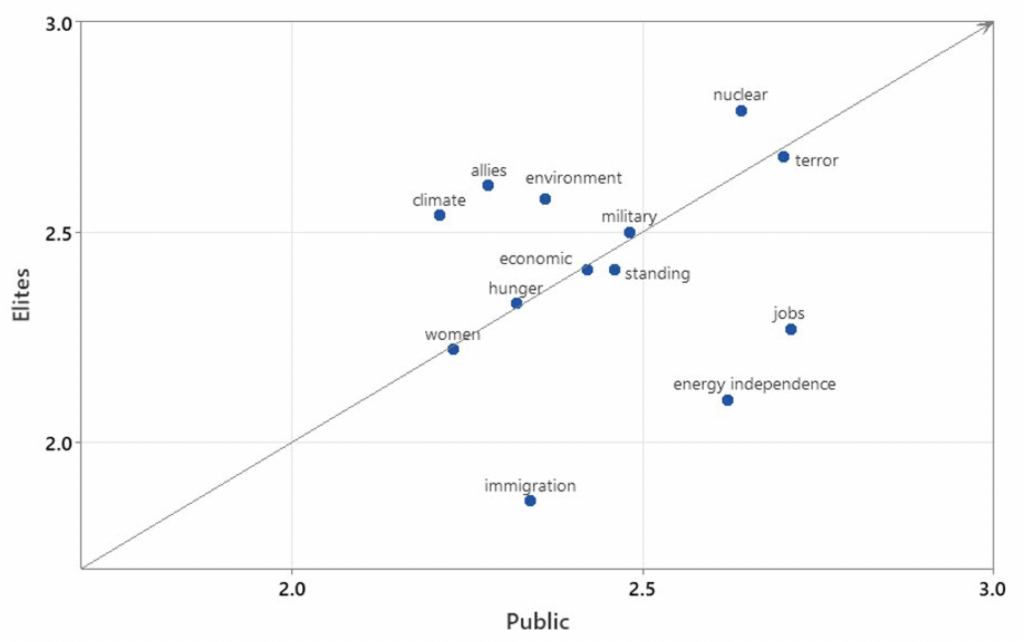

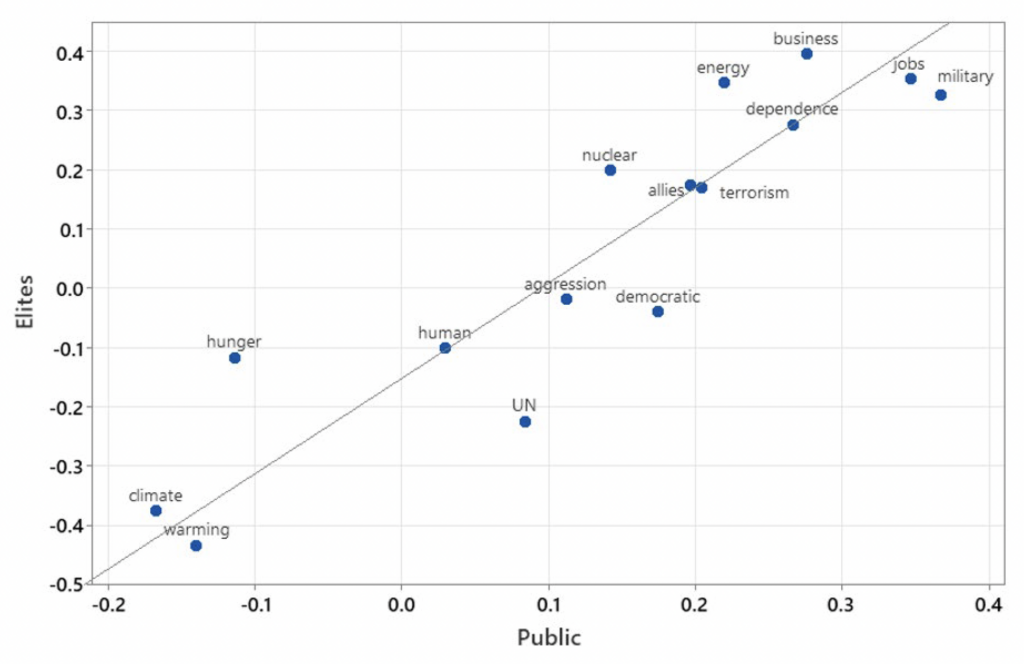

Figure 2 gives more detail on elite and popular ratings of the potential goals in 2016. The horizontal axis shows ratings in the public and the vertical line shows the ratings among elites. The upward-sloping line represents equal scores in both groups—the ones represented by points below this line are rated as more important by the general public and those represented by points above the line are rated as more important by elites.

Immigration is one of three items that the public rates as substantially more important than elites do: the others are “protecting American jobs” and “attaining U.S. energy independence.” On the other side, elites rated limiting climate change, improving the global environment, defending our allies’ security, and preventing the spread of nuclear weapons as more important than did the public. Page and Barabas (2000, 350), using CCGA surveys from the 1970s to the 1990s, concluded that the public “tends to favor foreign policy objectives of protecting immediate national self-interests, especially economic prosperity and physical safety.” The 2016 results suggest that this generalization remains true.

Observers such as Noonan and Douthat are correct in one sense: there is a longstanding gap between elite and public views on the priority of the issue. However, the gap did not produce a popular “backlash” in the sense of a reaction against the elite position: rather, both the public and elites moved in the same direction, and the gap between elite and popular opinion became somewhat smaller.

Figure 2. Public and Elite Foreign Policy Goals, 2016

What is the source of the differences between elite and popular opinions on this issue? Differences in knowledge and values are potentially important, but measuring them is intrinsically difficult, and the CCGA surveys do not include any relevant questions. However, it is possible to investigate the effects of demographic differences between elites and the public. Table 1 shows the results from regressions of ratings of the importance of “controlling and reducing illegal immigration” using the 2016 sample of the public. Model 1 includes education, income, age, gender, race, and Hispanic ethnicity as predictors. Education is coded into three categories: no college degree, bachelor’s degree, and post-graduate study. Household income is coded into groups going from 1 (less than $5,000) to 19 ($175,000) or above, while age is measured in years.

Blacks, Hispanics, younger people, and more educated people rate illegal immigration as a less important priority, while the estimates for gender and income are not statistically significant. Given the estimates from this model, the predicted value of the dependent variable in a group with the composition of the elite sample in terms of race and ethnicity, age, gender, and education is 2.24.4The elite sample did not include a question on income. To obtain the predicted value, I assumed that the mean value among elites was 18 ($150,000–$174,000). This is lower than the mean value in the sample of the public (2.34) but well above the actual mean in the elite sample (1.86). That is, only about 20% of the difference between elite and public opinion on this question can be accounted for by the demographic composition of the elite sample.

Although elites are more educated than the public (about 75% have some graduate education), most of the impact of this factor is offset by the differences in ethnic composition (only about 1.5% of the elite sample is Black and 4% is Hispanic) and age (the average age in the elite sample is about 7 years greater than the average in the public). Moreover, all group differences in opinion in the public are small relative to the opinion differences between the public and elites. For example, education and age are two of the strongest influences on opinion, but the mean rating of importance is 2.25 among college graduates and 2.14 among college graduates under 30, still substantially larger than the elite rating.

In addition to the demographic differences, the elite and public samples also differ in terms of party identification. In 2016, 52% of the elites identified as Democrats, 17% as Republicans, and 31% as independents, while the public was 36% Democrats, 28% Republicans, and 35% independents.5There was some difference in this direction in all of the surveys, but it was stronger in the later ones. Therefore, Model 2 adds controls for party identification. The estimated effect of Black race is much smaller than in Model 1 and not statistically significant—that is, there is no clear difference between Black and white opinions after controlling for party. The estimates for Hispanic ethnicity and education are smaller than in Model 1, but remain significant, while the estimate for age remains about the same. Finally, there are large and statistically significant differences between Democrats and Republicans. Applying the estimates from Model 2 with the composition of the elite sample produces an estimate of 2.04, approximately halfway between the observed means in the public and elite samples.

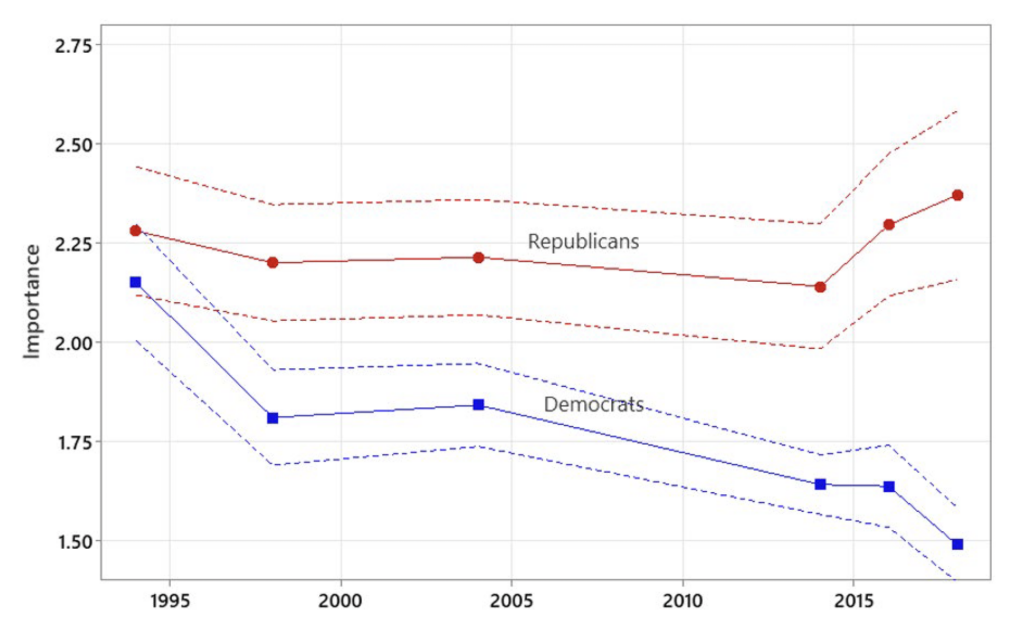

Figure 3. Ratings of the Importance of Reducing Illegal Immigration by Party, Elites

Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals

The results from Table 1 show that, as of 2016, there were partisan differences of opinion in the public. Figure 3 shows the course of partisan differences among elites from 1994 to 2018.6The values for independents are not shown in Figures 3 and 4 in order to maintain readability; in both cases, they are in between the values for Democrats and Republicans. Republican opinions on the importance of controlling and reducing illegal immigration stayed about the same over the whole period, while Democrats moved towards giving the issue a lower priority. As a result, the partisan gap grew substantially. In fact, it is not clear if there was any gap at the beginning of the period since the party differences were not statistically significant in the 1994 survey.

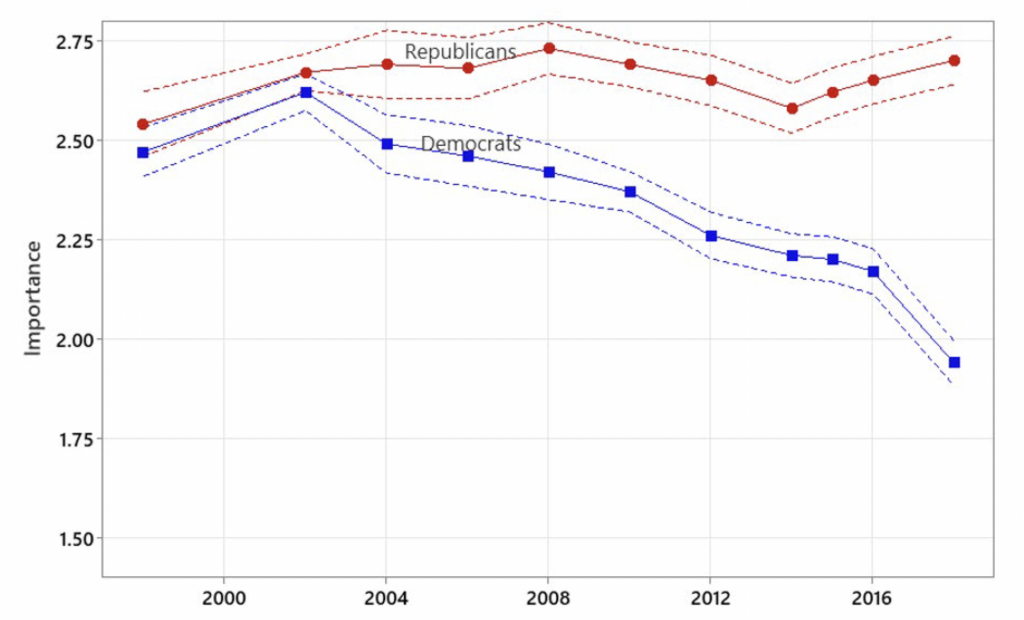

Figure 4 shows average ratings of the importance of controlling and reducing illegal immigration by party identification in the general public. The 1994 survey of the public did not ask about party identification, so the earliest year included is 1998. Among Republicans, there is no clear trend over the period, although there is some variation over time beyond what could be expected from sampling error. Among Democrats, ratings increased between 1998 and 2002, but declined steadily after that time. Partisan differences were small and not statistically significant in 1998 and 2002, but have grown steadily since that time.

Figure 4. Ratings of the Importance of Reducing Illegal Immigration by Party, General Public

Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals

Figures 3 and 4 show that partisan differences increased among both elites and the public. Figure 5 highlights this point by showing the size of the gap between Democrats and Republicans in elites and the public. It is consistently larger among elites, but there is a strong upward trend in both groups. The growth seems to have accelerated in recent years: in the public, the partisan difference doubled between 2014 and 2018.

These results indicate that there was something approaching an elite consensus in 1994, but that since 1998 elites have been divided by partisanship. Although partisan differences among elites have increased on many issues over the period, the shift between 1994 and 1998 was not simply a reflection of a general movement. Fourteen of the potential foreign policy goals were included in both surveys, and the association with partisanship declined between 1994 and 1998 for eleven of them. “Controlling and reducing illegal immigration” was the only one for which there was a substantial increase in partisan divisions. During those years, political leaders from both parties stressed their opposition to illegal immigration: “Bill Clinton’s mid-1990s State of the Union Addresses boasted of hitting targets for the arrest and deportation of illegal immigrants” (Citrin, Levy, and Wright 2023, 39). However, Republicans went further in this direction by trying to bar illegal immigrants from receiving benefits from various programs, most prominently in California’s Proposition 187 and the 1996 welfare reform bill. It seems plausible that the conflict over these measures increased partisan polarization among elites by forcing them to take sides.

Converse (1964) and Zaller (1992) propose that partisan divisions on issues appear first among elites and then are transmitted to the public. Campbell (2016) offers an alternative account of the growth of polarization in which elites were pulled apart by pressure from their partisan “base.” The fact that partisan divisions on illegal immigration have consistently been stronger in elites than in the public suggests that Campbell’s account does not apply to this case. However, it is not possible to say whether the increase in polarization among elites caused the increase in the public, as the Converse-Zaller model implies, or if both reflect some common factor.

Figure 5. Party Differences in Rating of Importance, 1994–2018

Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals

There are also some differences of opinion among specific elite groups, even after controlling for group differences in party identification. Business, labor, Congress, and members of the executive branch give illegal immigration higher priority, while educators and the media give it a lower priority, and religious leaders and think tanks are in the middle. The higher priority given by Congress and the administration may be because they need to take public opinion into account, while labor leaders may be concerned by the possibility of immigrant competition for members’ jobs.

The position of business is more surprising since it is often said that most businesses benefit from having a larger supply of potential workers. Business is more Republican than the other elite samples, so at least some of the difference is probably the result of partisanship. A sense of the size of the group differences can be obtained by restricting attention to independents: in the elite sample, their mean rating of the importance of controlling and reducing illegal immigration was 2.17 for business, 1.78 for educators, and 1.77 for the media. Because of small numbers in the individual groups, it is difficult to be sure about whether there has been any change in relative position of groups, but there is evidence that business has shifted towards giving a higher priority to controlling illegal immigration. Finally, the elite survey included a military sample in 2014; they rated controlling illegal immigration as a more important goal than did members of other elite groups.7Since there was no military sample in other years, it is not included in any of the analyses.

Figure 6. Correlations of the Priority of Reducing Illegal Immigration and Other Issues

The final issue is the relationship between the priorities given to immigration and other issues. Figure 6 shows the correlations of the ratings of the importance of reducing illegal immigration and with ratings of other goals among the public and elites in 2014. This year was chosen because it has relatively large samples for both elites and the public. The horizontal axis shows correlations in the public, and the vertical shows the correlation among elites. Most of the correlations are in the same direction and relative size in both groups—for example, controlling illegal immigration has a strong positive correlation with maintaining superior military power among both elites and the public—but there seem to be some deviations from the general pattern.

The data can be analyzed by a model in which the correlations among both the elite and popular samples reflect an underlying latent variable. This model implies that group differences in correlations are simply a matter of size: the underlying pattern is the same in both. The model can be written as:

(1)

(2)

The subscripts and

indicate elites and the public, while indicates the item. The scale of the latent variable is undefined, so it must be fixed by setting it at 1.0 in one of the groups. The constant term

can be regarded as representing the relative strength of “response set”—that is, a tendency to give the same answer to all questions—while

indicates the relative strength of the pattern of correlations involving different items. The maximum likelihood estimate for equation (2) is

, and the standard error of the term

term is 0.038. The diagonal line in Figure 6 represents the predicted values from this model.

Although the latent variable model fits the data well, there are several cases in which the differences between the actual and predicted correlations in the two groups are statistically significant. The two largest deviations involve the correlations of controlling illegal immigration with combatting world hunger and with strengthening the United Nations. With the UN, there is a negative correlation among elites, but a positive correlation among the public—that is, relative to elites, members of the public are more likely to rate it similarly to controlling illegal immigration. In the case of combatting world hunger, the correlation is negative among both groups, but is closer to zero than predicted among elites—that is, elites are more likely to rate it similarly to controlling illegal immigration.

These results are not definitive, but they suggest that there are some differences in framing—that is, in the way that the public and elites make connections among issues. Specifically, elites are more likely to connect the goal of controlling illegal immigration with the goal of combatting world hunger, while the public is more likely to connect it with the goal of strengthening the United Nations. It seems possible that these differences reflect greater knowledge among elites: they are more likely to see global inequality as an important cause of illegal immigration and to be aware of the limited effectiveness of the United Nations in dealing with the issue. The difference involving the United Nations may also reflect the popular orientation towards “multilateralism” noted by Page and Barabas (2000): the public prefers to work through multilateral organizations, while elites focus on bilateral agreements or more limited alliances.

Discussion

One finding of this paper is that elites consistently give a lower priority to controlling illegal immigration than the public. Little of this difference in opinions is the result of demographic differences. A second finding is that, despite the difference in average opinion between elites and the public, there is not an elite consensus. Elites have been divided by partisanship at least since 1998, and partisan differences are consistently larger among elites than in the public. Moreover, there are differences of opinion among elite groups, even after controlling for partisanship. A third is that the mid-1990s appear to have been a crucial period for the development of partisan differences among elites. Finally, there are some differences in the pattern of correlations of opinions about the importance of controlling illegal immigration and other foreign policy goals among elites and the public. That is, there are differences in the ways that elites and the public connect controlling illegal immigration to other goals.

Although there will inevitably be some differences between elite and popular views, large and enduring gaps present a problem for democracy (Page and Barabas 2000). When trust in political elites is high, the public may be willing to accept the judgment of elites, even if they do not fully agree with it. However, when trust is low, the public may rise in opposition to the policies favored by elites. Levy, Wright, and Citrin (2016, 672) suggest that increasing influence of public opinion may be making it more difficult for political leaders to reach agreement on immigration reform: “The proliferation of talk radio and partisan cable news outlets increases the opportunity for conservative politicians to frame the issue and mobilize opposition.” In some cases, the ability to mobilize popular opinion against elites may be a positive development, bringing fresh ideas and approaches into the political sphere (Hochschild 2012). However, history suggests that this is generally not the case with illegal immigration—the usual result is “get tough” policies that are initially popular but are ineffective or have unanticipated negative consequences that cause them to lose support.

If we assume that on this issue elite opinions reflect a better understanding, how the gap between elite and public opinion be addressed? One approach is for political leaders to try to appeal to popular opinion by adopting tough language and highlighting enforcement measures while avoiding mention of any policies that might be criticized as “soft.” Bill Clinton and some other Democratic politicians took this approach in the 1990s (Citrin, Levy, and Wright 2023). The potential drawback is that such efforts may draw more attention to the issue while leaving the possibility of being outbid by politicians who call for a harder line. An alternative approach, which has been favored by Democrats more recently, is to try to downplay the issue of illegal immigration and focus on other issues where their positions are more popular. The drawback of this approach is that if the issue is important to the public, avoiding it may only fuel popular discontent.

A different way to deal with the gap is to try to reduce it by changing public opinion. Statistics related to illegal immigration are not released regularly and receive little attention when they appear. The most recent official estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population were released in 2021 and cover January 2015–January 2018 (Baker 2021). Moreover, most people cannot gain much information from their own experience, so knowledge of illegal immigration comes mainly from media coverage. Journalists have a natural tendency to focus on unusual occurrences, so illegal immigration generally gets attention from the media only when there is some event like a surge that strains enforcement capacity or deaths of people attempting to cross the border. Consequently, people may develop a sense of permanent crisis: that the volume of illegal immigration is always increasing and efforts to control it are always on the verge of collapse. More effort by both government and the media to regularly collect and report information might give people a more accurate sense of the situation—for example, by making them aware of declines as well as increases in numbers.

Finally, the pattern of correlations among different opinions may provide insight into the kinds of arguments or actions that would move public opinion. For example, the positive association between the goals of strengthening the United Nations and controlling illegal immigration suggests that involving the United Nations, even in a symbolic way, may help to persuade the public that the issue is being taken seriously.

Many observers have sensed that there is a difference between elite and popular opinion on immigration, but the scarcity of information on elite opinions means that we do not know much about the nature of that difference. This paper is meant to provide a first step towards a better understanding.

Appendix

References

Baker, Bryan. 2021. “Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2015–January 2018.” Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics.

Cable News Network (CNN). 2011. CNN/ORC Poll: Economy/Politics, Question 57, USORC.091511.R28, Opinion Research Corporation, (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research).

Campbell, James E. 2016. Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 336.

CBS News. 2015. “CBS News Poll: Donald Trump Leads GOP Field in 2016 Presidential Race.” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cbs-news-poll-donald-trump-leads-gop-field-in-2016-presidential-race/.

Chicago Council on Foreign Relations. 1995. American Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy 1995. Chicago: Chicago Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://globalaffairs.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/1994–Chicago-Council-Survey-PDF-Report.pdf.

Chicago Council on Global Affairs. 2023a. Chicago Council Surveys. https://globalaffairs.org/explore-research/lester-crown-center-us-foreign-policy/chicago-council-survey.

Chicago Council on Global Affairs. 2023b. Opinion Leader Surveys. https://globalaffairs.org/explore-research/lester-crown-center-us-foreign-policy/chicago-council-survey. Citrin, Jack, Morris Levy, and Matthew Wright. 2023. Immigration in the Court of Public Opinion. Cambridge: Polity, 192.

Converse, Philip E. 1964. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics.” In Ideology and Discontent, edited by David E. Apter. New York: Free Press.

. 1975. “Some Mass-Elite Contrasts in the Perception of Political Spaces.” Social Science Information 14: 49–83.

Douthat, Ross. 2019. “Between Folly and Cruelty on Immigration.” New York Times, 6 July. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/06/opinion/sunday/between-folly-and-cruelty-on-immigration.html.

Freeman, Gary P. 1995. “Rejoinder.” International Migration Review 29: 909–13.

Gallup. 2023. “Immigration.” https://news.gallup.com/poll/1660/immigration.aspx.

Hochschild, Jennifer L. 2012. “Should the Mass Public Follow Elite Opinion? It Depends. . .” Critical Review 24: 527–43.

Kertzer, Joshua D. 2022. “Re-Assessing Elite-Public Gaps in Political Behavior.” American Journal of Political Science 66: 539–53.

Lakoff, George and Sam Ferguson. 2006. “The Framing of Immigration.” Rockridge Institute. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0j89f85g.

Levy, Morris, Matthew Wright, and Jack Citrin. 2016. “Mass Opinion and Immigration Policy in the United States: Re-Assessing Clientelist and Elite Perspectives.” Perspectives on Politics 14: 660–80.

McClosky, Herbert. 1964. “Consensus and Ideology in American Politics.” American Political Science Review 58: 361–82.

Noonan, Peggy. 2016. “Trump and the Rise of the Unprotected.” Wall Street Journal, 27 February. Retrieved from https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/peggy-noonan.

Page, Benjamin I. and Jason Barabas. 2000. “Foreign Policy Gaps Between Citizens and Leaders.” International Studies Quarterly 44: 339–64.

Stokes, Donald E. 1963. “Spatial Models of Party Competition.” American Political Science Review 57: 368–77.

Stouffer, Samuel A. 1955. Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties. New York: Doubleday. Trump, Donald. 2015. “Presidential Announcement Speech.” Time, 16 June. https://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/.

Wright, Matthew, Morris Levy, and Jack Citrin. 2016. “ Public Attitudes Toward Immigration Policy Across the Legal/Illegal Divide: The Role of Categorical and Attribute-Based Decision-Making.” Political Behavior 38: 229–53.

Zaller, John R. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 388.