Pete Amador’s list of people waiting for him is getting longer every day. Amador runs a home healthcare agency in Boise, Idaho and business is booming. As he puts it, “People are calling hourly asking for help.” Amador is pressed for caregivers to serve the growing elderly population.

In Amador’s quest to serve those in need of home healthcare services, some of his best allies have been refugees. In cities across the country facing aging populations, refugees have proved a valuable resource for businesses and communities looking for workers. Tara Wolfson, director of the nonprofit Idaho Office for Refugees, says desperate companies and employment agencies are calling numerous times a week looking for refugees to fill their labor needs. With about 77.1 percent of refugees at working age and high labor force participation within the refugee population, they can fill the gap in key industries and fit the needs of local businesses.

A fundamental insight from the economics of immigration is that we’re better together. Refugees help keep cities strong and lively. The refugee cap should reflect the contributions that refugees can make. Raising the refugee cap is a good place to start in making it possible for more businesses like Amador’s to find workers to serve their customers. Communities around the country will be better served if federal policy allowed more refugees to meet the needs of their local businesses.

An aging population and fewer babies

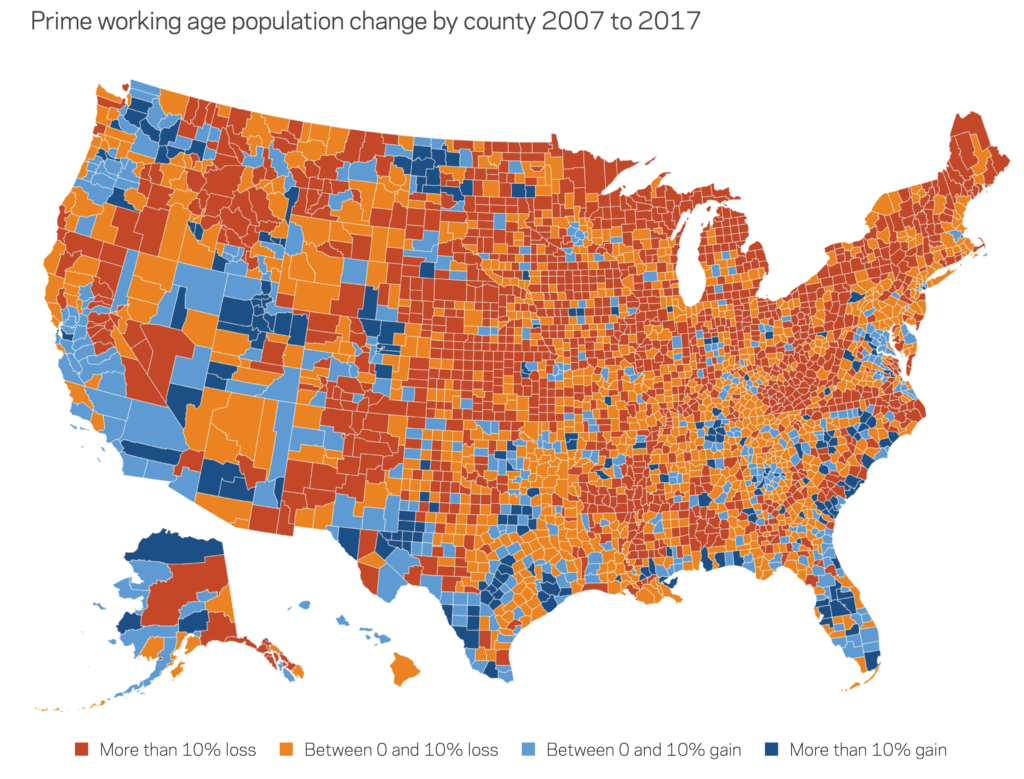

Amador is not alone in needing more workers than he can find. Similar stories are playing out in many communities across the country, particularly in Heartland and Rustbelt communities, as shown in the map below. Restaurants, grocery stores, and companies are facing a shrinking labor pool that leaves them without the workers they need. In more than half of its counties, Idaho’s prime working age population is shrinking.

Source: EIG estimates and map of county population change from 2007-2017.

And it’s not just people leaving one state for greener pastures in another. Overall, population growth has slowed—especially in the working-age population. Since 2018, the U.S. has faced its lowest annual population growth rates since at least the early 1900s. From July 1, 2019, to July 1, 2020, the growth rate was at just 0.35 percent, as compared to a growth rate of 0.73 percent from 2010 to 2011. This slowdown largely represents declining fertility rates within the country over about the last 15 years.

The flip side of lower fertility rates is that the U.S. is made up of an increasingly aging population. An estimated 73 million Americans will be aged 65 and older in the next 10 years. So employers face a labor shortage at both ends—many people are about to leave the workforce and not as many new workers are coming in. The working age population is not growing fast enough to fill the gaps left in the workforce left by an aging population.

The growth of the over-55 population compared to the growth of the under-55 population is impressive. The number of people over age 55 grew by 27 percent between 2010 and 2020. In contrast, the growth rate of the population under 55 grew by just 1.3 percent. It’s a widespread problem across the country. Over the last decade, 80 percent of counties in the U.S. have lost population ages 25 to 54. Refugees can help soften the challenges of population decline.

Refugees contribute to easing labor shortages

Refugees often provide much-needed labor in industries otherwise facing a labor shortage. In particular, refugee contributions are a source of strength to both healthcare and manufacturing businesses across the U.S.

The aging population puts special strain on the healthcare sector. More people need care as they age and fewer workers are in a position to offer it. Although they are only a piece of the puzzle, refugees can help relieve labor shortages in the industry. For example, about 15.6 percent of all refugees work in the healthcare sector.

Amador’s home healthcare agency has seen how refugees can alleviate labor shortages in low skilled healthcare positions. Refugees already make up about 70 percent of his workforce. He told reporters that he could easily hire about 50 more people—if he could find them.

In 2018, 27 percent of refugees were personal care and home health aides. Refugees make a real difference for businesses like Amadors and in the lives of Americans seeking care.

In the manufacturing industry the same story plays out—refugees provide a labor source for companies that need workers. There are 500,000 job openings in the manufacturing sector today, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 2015, 20.3 percent of refugees working in the U.S. held jobs in manufacturing. More refugees worked in manufacturing than any other industry that year, healthcare being second. By 2030, analysts at the consulting firm Deloitte estimate that there will be an estimated 2.1 million unfilled manufacturing jobs. Allowing more refugees to come to the U.S. could help fill that gap.

Refugees also enable the expansion of existing businesses. Even if they’re getting orders or requests for services, businesses can’t operate without workers. Take the manufacturing firm Molded Fiber Glass Companies in South Dakota as an example. From 2011 to 2015, the company more than tripled its production capacity and employs 600 people today. That’s four times more than the 150 workers that the company employed in 2011. The company’s senior vice president attributes this quadrupling to their investment in refugees. The company pays for its immigrant workers to take English-language classes as well as college courses related to their jobs. “The refugees have begun to meld into the community, so it’s been an economic boom for [the area].”

A similar illustration of refugee-led expansion is Buffalo Wire Works in New York. The company relies on refugees and immigrants to fill its positions. Out of 170 employees, 71 are refugees from 21 different countries. Now the company reaches out to local resettlement agencies to advertise vacant positions.

Refugees can’t solve all of the country’s demographic and economic challenges alone. But they are already playing a part in revitalizing local communities and economies. This means more opportunities for natives, not fewer.

How refugees complement natives

A common concern about taking in more refugees or immigrants is that the additional workers will take away jobs or wages that natives would otherwise receive. However, research is clear that rather than view foreign-born residents as a threat, we should view them as a complement to the native workforce. Refugees compete for different types of jobs than most natives. With their different skills and training, immigrants are opening up opportunities for natives to do more valuable work elsewhere.

Most academics also agree that natives and foreign-born residents have different skill sets and compete for different types of jobs. That’s important because economies grow as workers are able to do more of what they’re best at. Economists see this as an example of comparative advantage. By capitalizing on what they’re best at, both refugees and natives gain. In short, we’re better together.

Think about comparative advantages between refugees and natives as if you ran a coffee shop. To keep the lights on and pay people, someone has to do the accounting and management. And to keep the customers coming in, someone needs to brew coffee, wipe tables, and wash the dishes. Our coffee shop owner might be able to do it all themselves at the beginning, but expanding will require that they hire someone. Immigrants often fill this need. The owner can do the accounting and design advertisements knowing that someone else is keeping the store in order and customers happy. Everyone is better off.

Comparing refugees and natives, one obvious difference is language ability. Studies have shown that when foreign-born people begin working in an industry, native workers already working in the industry tend to move into roles that require better language skills such as administrative and managerial positions. Natives have a natural advantage there over refugees who have less experience or training in English.

Raise the refugee cap to at least 125,000 each year

Although refugees could help to expand businesses and meet the needs of U.S. companies, current policy creates real barriers to allowing this to happen. Refugee resettlement in the U.S. has reached an all-time low in recent years.

Between 2010 and 2017, the U.S. admitted many more than in the last two years, ranging from 50,000 to 80,000 refugees a year. During COVID-19, refugee resettlement numbers fell dramatically, from 30,000 in 2019 to 11,814 in 2020.

In 2021, President Biden announced plans to take in just 15,000 refugees, but then raised that number to 62,500 after public backlash over his campaign promise to allow significantly more people to enter the U.S.

While a cap of 62,500 for this year is a good start, the U.S. should set a goal to take in 125,000 refugees the following year. At that rate, the U.S. can begin working toward achieving the same refugee resettlement numbers per capita as Canada. Our Northern counterpart resettled 756 refugees per million residents in 2018. If the U.S. took in the same amount of refugees per million residents, the U.S. would have resettled about 250,000 refugees in that year.

Refugees can play a powerful role in easing the problems associated with population decline and a declining working age population. They have already contributed to easing labor shortages in industries like healthcare and manufacturing. The first step to making this a reality is raising the refugee cap to 125,000 refugees each year. This short-term goal would allow time to build up resettlement capacity following recent all-time lows. If Canada can embrace the ability of refugees to help make their economy more resilient, the U.S. can too. We’ll all be better off for it.