The United States refugee resettlement program is like a paddleboard that has lost its keel.

The keel is a little fin at the back of the paddleboard that sticks in the water, stabilizing and steering the board. Without it, the paddleboard veers to the right and the left uncontrollably, making it impossible to stay on a straight course.

Without a keel, the water takes you where it wants to. With it, you can go where you want to.

Like a paddleboard without a keel, the refugee resettlement program in the United States has a history of veering to the right and to the left. In the current system, the president of the United States determines the annual refugee cap. This has politicized refugee resettlement.

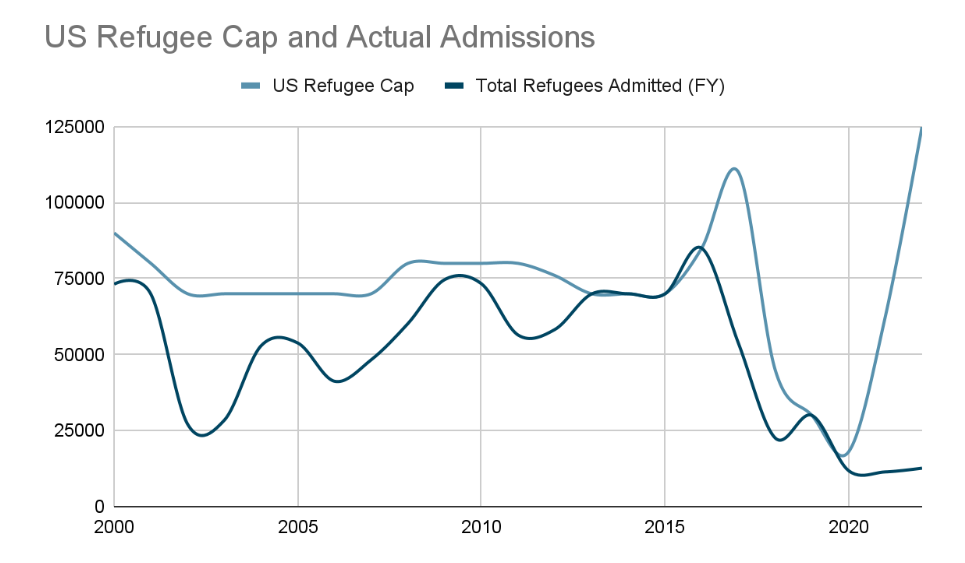

On the right, in 2020 the Trump Administration dropped the refugee cap to a record low of 15,000. On the left, in 2021 the Biden Administration more than quadrupled the cap to 62,500. Two years after the record low, the refugee cap is now the highest it has been in over 20 years at 125,000. And yet, we still won’t come close to that number in actual refugees admitted.

The instability of the refugee program makes the resettlement system ineffective. We need a robust refugee resettlement system that is tied less to political whims and more to real-world economic conditions. In light of the Afghan and Ukraine refugee crises, now is the time to fit the refugee resettlement program with a keel.

What does today’s refugee resettlement program look like?

The partisan back and forth has crippled our refugee resettlement program. The timing could not have been worse.

Global refugee numbers have increased dramatically in the past decade to record highs. According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) there are currently 26.4 million refugees around the world, the highest it has been since the establishment of the UNHCR in 1950. The scale of other recent refugee numbers pales in comparison to what is happening today.

The Syrian Civil War was followed by an exodus from the Middle East in 2015. In 2021, thousands of Afghans fled their homes after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan. But the Russian invasion of Ukraine has resulted in Europe's biggest refugee crisis since World War II. As of June 1st, 2022, about seven million Ukrainians had fled the country since Russia’s invasion.

Despite the growing need for more resettlement, last year, as the worldwide refugee count broke records, the United States dropped to its lowest admissions level ever. Even with the cap set to 62,500, the US took in just 11,411 refugees. This year’s resettlement levels are not looking more optimistic. As of the most current data in June of 2022, the US is on track to resettle only a tenth of its 125,000 goal.

Neither 2021’s nor 2022’s low admissions level can be blamed on a low cap. The 2021 cap was set at 62,500. However, the US only let in a fifth of what we could have. In 2022 we may resettle an even smaller fraction of what we could.

If the cap isn’t the reason for recent low admission levels, what is? The answer is simple: We don’t have the infrastructure to process 62,500 refugees, much less 125,000.

In 2017, under the Trump administration, the State Department concluded that if fewer refugees are coming to the US, then fewer resettlement offices will be needed. In 2017 they informed the nine major refugee resettlement agencies that any office expecting to assist fewer than 100 refugees the following year would be closed. This led to the closure of 134 offices, cutting resettlement capacity by 38 percent.

Now US refugee resettlement capacity is so strained that regular refugee resettlement entirely stops when crises arise.

In September 2021, after the Taliban took control of Afghanistan, the Department of Homeland Security launched Operation Allies Welcome to expedite the resettlement of Afghan evacuees. Yet, in order to meet the immediate need to resettle thousands of Afghan evacuees, the Federal Government put the ongoing Refugee Resettlement Program on hold for two and a half months from October to January. The resettlement program simply did not have the capacity to process the Afghan refugees in addition to the regular refugee flow.

The reduced capacity of the resettlement program doesn’t just affect the number of incoming refugees we can help. It also affects refugees who have already been living in the country for years.

In addition to processing refugees who just arrived in the country, resettlement offices also offer services to refugees up to five years after they arrive in the country. These services include English classes, job search assistance, and school registration. These resources are vital tools in helping refugees assimilate into the United States.

The root of the problem isn’t that many offices were closed or even that the number of refugees admitted to the country drastically decreased for a few years.

The root of the problem is the unpredictability of the refugee resettlement process.

The unpredictability of the refugee cap becomes apparent when we consider that the refugee cap was initially set at 110,000 in 2017. By the next year it dropped to 45,000, a decrease of nearly 60%.

Imagine trying to run a restaurant without an accurate estimate for how many customers you will be feeding. You would make poor judgments on how many people to hire and how much food you need. Unpredictability wastes valuable time, energy and resources.

In the same way, this volatility in resettlement numbers makes it hard for resettlement agencies to plan ahead and anticipate the need for refugee resettlement a few years in advance.

It’s time to fix the resettlement program

Fixing the refugee resettlement program is a two-part problem:

The first half of the problem—a refugee cap that changes with politics—can be solved with simple math, a formula that takes into account the US economy as well as worldwide refugee levels.

The second half of the problem—never actually meeting our refugee caps—can be solved using existing computer-based matching systems that automatically match refugees with the communities best able to support them.

First: Use a formula to set predictable resettlement levels

A simple formula can create more predictability and stability for refugee admission levels. Two major factors should be considered when setting the annual refugee cap: our nation’s capacity to resettle refugees relative to the health of the economy and the global need for resettlement.

There are many potential measures of the economy’s health. A simple metric is the annual change in employment rate. Specifically, the formula would use the change in the employment rate from one year to the next. If the employment rate increased from last year to this year, the formula would allocate more spots to refugees in the annual cap.

To measure the global need for resettlement, the formula could use UNHCR’s Refugees in Need of Resettlement (RINOR) metric. This category is a small portion of all the refugees in the world. Only those who are most in need of permanent resettlement are included in this measure. The current RINOR count is estimated at 1.47 million.

In line with a recommendation from the National Immigration Forum, the formula could use 10% of the RINOR metric as a baseline. This could be higher or lower, but would set a clear, predictable path for resettlement organizations to plan for.

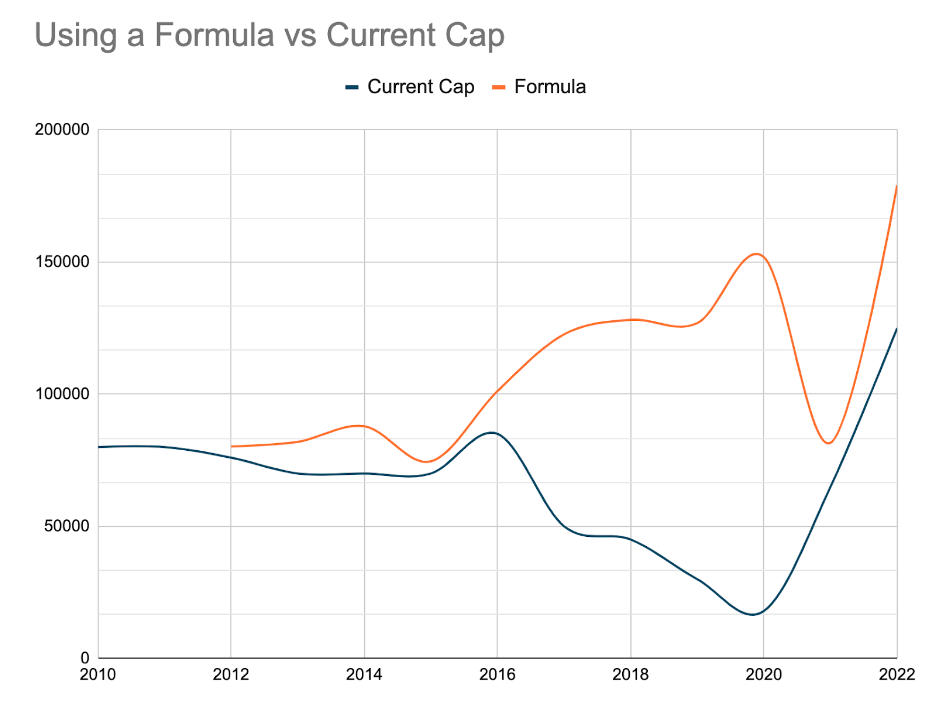

The graph below shows a rough comparison of what resettlement rates would look like with the formula relative to the historical refugee cap.

The UN began using RINOR in 2011, so our hypothetical cap starts the following year. The major factor driving the refugee cap in this system is the global need for refugee resettlement. However, as the employment rate increases or decreases, the formula automatically adjusts to take in slightly less than 10% or slightly more than 10% of that year’s RINOR level.

For instance, from 2014 to 2015, the employment rate increased from 68.14% to 68.70%---a difference of 0.56%. In response, the 2016 resettlement level would be set at 10% of the 2015 RINOR level, plus the difference in employment rates for a total of 10.56%. With a RINOR level of about 958,000 in 2015, the refugee cap for 2016 would then be about 101,000 refugees.

That fluctuation is largest in 2020 because of COVID-19, but quickly recovers because of recent dramatic job growth.

Second: Expand the use of computerized refugee matching systems

One of the important implications of this proposed formula is that the US will need to improve its resettlement system to take in more refugees. Currently, refugee resettlement is mostly done by hand. Case managers assess where to best relocate an individual based on current demographics of refugees. This makes it inefficient and slow. It isn’t a feasible long-term solution for resettling people quickly and effectively.

The fix is to automate the refugee relocation.

The US already uses computerized refugee matching systems, but only on a trial basis. Resettlement organizations and the official US program should scale up those trials for primetime.

One of these automated programs is called Annie MOORE (Matching and Outcome Optimization for Refugee Empowerment). It’s named after Annie Moore, the first immigrant to set foot on Ellis Island in 1892.

Similar to how dating sites find the “perfect match,” Annie MOORE matches refugees to the best-fitting resettlement location. The algorithm matches the refugees' preference for resettlement to the preferences and capacities of host communities, such as housing availability, opportunities for employment, or availability of English courses.

By automating an important step in the resettlement process, caseworkers are able to resettle more refugees, using fewer resources and less time. It also allows them to spend more time on complex cases. Matching programs still give caseworkers the flexibility to make tweaks based on their experience.

The refugee resettlement agency HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) has been using Annie MOORE since 2018.

Research suggests that these refugee matching trial programs are working well. In addition to increasing efficiency, refugee matching systems can increase job placement by as much as 38%. Better job placement improves integration into the community and enhances the benefit refugees are to the communities they move to.

Matching systems create a win-win situation between refugees and the communities they relocate to.

Improved refugee programs can meet today’s humanitarian challenge

It is time to step up our game and update our resettlement system so that we can welcome more refugees. Three months after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, about seven million Ukrainians have fled the country. Poland has taken in the majority of these refugees, simply because of its proximity to Ukraine. Considering the United States is geographically far removed from the conflict, it isn’t surprising comparatively few refugees have come to the United States. But that doesn’t mean we should stand idly by.

The waters of asylum and refuge are currently very choppy, and the United States is long overdue a keel. If we wish to stand by our allies in Europe and open our arms to Ukrainians, we should act now to fix the resettlement system and steady our course.