The Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) recently released a new analysis comparing crime reporting rates among immigrants and natives. Their fundamental finding is that reporting rates in the two groups are relatively similar. When there are differences they tend to favor the immigrants, meaning that immigrants may be more likely to report crimes. Other researchers, notably Min Xie and Eric P. Baumer, have reached similar conclusions.

Research showing similar reporting rates between immigrants and natives is an encouraging sign that immigrants play a part in protecting the communities that they join. To this end, the CIS report makes several valuable policy suggestions. For example, CIS notes the need for police departments’ community outreach to emphasize that victims are not targets for immigration enforcement. Reducing language barriers by hiring law enforcement officers who speak languages that the communities they serve speak is another valuable suggestion.

However, CIS also claims that its findings indicate sanctuary policies, which limit how local law enforcement works with federal immigration officials, are pointless. This conclusion is misconstrued. The data CIS analyzed does not support it.

Specifically, the data underlying the CIS report cannot speak to domestic violence, a major motivation for sanctuary policies. This constraint is a particularly troubling problem. Other research clearly shows a chilling effect in which immigrants who are victims of domestic violence are less likely to come forward when local law enforcement works with federal officials. Notwithstanding CIS’s contribution to what we know about immigrant reporting, looking only at a single dataset fails to paint a full picture.

A broader view of the research shows that heavy-handed enforcement policies endanger some immigrants and fail to reduce crime. In contrast, policies that target serious offenders likely improve public safety. In sum, evidence suggests that policymakers can best protect the public by taking welcoming stances towards immigrants.

Why immigrants may be less likely to report crime

Law enforcement among immigrant communities is a challenging task because many legal immigrants and natives live in mixed-status homes. That is, the parents may be undocumented and the children may be legal citizens. Or a grandfather living with a legal family may not be authorized to be in the country. Around 10.6 million citizens live with undocumented immigrants, according to estimates using Census Bureau data.

The number of mixed-status homes and undocumented immigrants creates a potential trade-off for public safety and law enforcement. If a police officer knocks on your door when one of your undocumented family members is home, then you may be less willing to talk with them. Or, you may be unwilling to report a crime or suspicious behavior because you don’t want to draw attention to your undocumented family members.

These kinds of concerns are magnified by partnerships between Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and local law enforcement. For example, some programs authorize local police officers to enforce federal immigration rules. ICE justifies these programs as a way to pursue dangerous criminals and keep communities safe.

These partnerships are a strange use of public safety resources. There is a clear consensus among crime and immigration researchers that immigration, illegal or legal, does not increase crime rates. In fact, many researchers find a “revitalization” effect from immigration. Because immigrants have lower crime rates, they make neighborhoods safer by moving into them. So why should local police spend time enforcing immigration laws?

The central concern when local law enforcement partners with federal immigration forces is that there may be a chilling effect on crime reporting. Immigrants in these areas may justifiably look at the police with apprehension in communities with these partnerships.

These chilling effects have been well-documented in domains besides crime reporting. For example, in areas with more local police involved in federal immigration enforcement, researchers have documented children being pulled out of schools and increased chances of Hispanic children repeating grades or dropping out. In some areas there is evidence that enforcement expands educational performance gaps between white students and Latino students. In addition, enforcement seems to chill participation in Medicaid, Headstart programs, and may even deter immigrants from seeking healthcare.

If increased enforcement deters immigrant populations from seeking education and healthcare, it seems likely that they may also be deterred from reporting crimes. This could reduce overall public safety.

When do immigrants report crimes?

To explore crime reporting, CIS and other researchers often use the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). It is a project of the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and a foundational dataset in criminology. In short, it surveys people on whether or not they have been the victim of a crime. Because it is a survey of victims it captures both reported and unreported crimes, an advantage over the other major crime reporting data, which is based on formal reports from police.

Like the CIS analysis, other research using the NCVS data have found that immigrants report crimes at about the same rates as natives. That’s an optimistic finding suggesting that immigrants are integrating well into their new communities. For the most part, immigrants are as willing as natives to come forward about crime.

However, researchers using the NCVS data have found limits that add nuance and depth to this broad conclusion that immigrants everywhere report crime at similar rates to natives. These studies analyze the data relative to local policy and the history of immigration in the area.

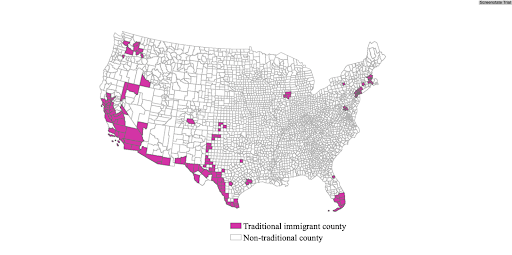

For example, one study looked at reporting rates among immigrants and natives in traditional destinations and new destinations. The set of older destinations for migrants are those that you’d expect. They spread from near the southern border out along the west coast with a few pockets in Florida and the northeast coast. But immigrant destinations have changed over the years. Immigrants are increasingly moving in from the coasts. In the study, newer destinations represent most of the country.

Source: Min Xie and Eric P. Baumer, “Neighborhood Immigrant Concentration and Violent Crime Reporting to the Police: A Multilevel Analysis of Data from the National Crime Victimization Survey*,” Criminology 57, no. 2 (2019): 237–67, doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12204. Note that the paper defines a traditional destination as a county “with long-established immigrant populations that exceeded the national average of immigrant concentration in 1990 (the immigrant share of the population was 7.9 percent in that year).”

To test this idea about differences between new and old destinations, the analysis used the NCVS data from 1996 to 2014. The researchers found that crime reporting in older immigrant-dense neighborhoods was similar to crime reporting elsewhere in the country. This suggests that immigrants in these older destinations were just as likely to report crimes as natives.

However, crime reporting rates dropped relative to the rest of the country in newer immigrant-dense neighborhoods. The native communities in newer destinations may not have developed clear relationships with immigrant populations yet.

In old destinations immigrants and their children have had generations to form relationships with city councils, mayors, and natives. Their children are often natives themselves, attending the same schools and playing on sports teams with other native children.

Crime researchers Min Xie and Eric Baumer point to the need for local governments and public agencies to reach out to immigrants in new destinations, much like CIS’s report advises. These governments should actively build trust among their new community members.

Other studies suggest that local policies can spur additional reporting. Using a larger amount of the NCVS data than CIS’s three-year analysis, researchers have found that limiting how local law enforcement and ICE interact (sanctuary policies) increases crime reporting by Latinos. This stands in contrast to CIS’s findings that these kinds of policies don’t affect reporting rates. The study, published in January 2021, uses data from 1980 to 2004. Although the data is several decades old, it suggests that reporting can be affected by local policies.

A key reason to limit ICE-police partnerships is to protect domestic violence victims

In their report, CIS acknowledges the motivation for many sanctuary laws is a desire to reduce domestic violence. Sanctuary policies put guard rails around how local police and federal immigration officials cooperate. For example, they limit when or for how long police will hold immigrants at the request of ICE.

As advocates for these policies often point out, a battered, undocumented person may be unwilling to come forward about abuse if they fear deportation or retribution by their partner. Sanctuary removes this power differential by creating institutional rules around law enforcement that put public safety first. In practice, a battered, undocumented woman could come forward because she knows that she won’t be investigated for her legal status when reporting the crime.

CIS quotes a 2018 statement by a Massachusetts state senator, “In a city like Lowell [with a large foreign-born population], those immigrants think that the local police officer is engaged in enforcing immigration law, they’re not going to report a crime or domestic violence. They won’t have that trust with police. That’s a main mission of this bill is to restore that trust.” This establishes that increasing the immigrant community’s trust in law enforcement as a key reason for the sanctuary bill. And it singles out domestic violence as a special concern motivating the adoption of sanctuary policies.

That domestic violence is of special importance in motivating sanctuary policies matters because the NCVS is not adequate for studying domestic violence. Other researchers using NCVS make this same point. CIS notes this limitation in their report, as well: “The sample of female immigrant victimizations for domestic partners is too small to provide reliable results for reporting of this specific crime.”

However, in a separate op-ed for the National Review, CIS researchers Steven Camarota and Jessica Vaughn make the following unjustified conclusion: “The 2017–19 NCVS indicates that the whole basis for sanctuary polices [sic] is a myth; it turns out that crimes against immigrants are reported to police at rates that match or often exceed those for crimes against the US-born.”

Other research uses methods that allow us to examine domestic violence rates without relying on the NCVS. The studies that don’t suffer from the limitations of the NCVS data paint a clear picture that sanctuary policies are effective at providing protection, just as proponents often say.

For example, research has documented that sanctuary policies save lives. Sanctuary policies have been found to reduce domestic homicides against Hispanic women by between 52 and 62 percent. Unlike other forms of domestic violence, homicides are difficult to conceal. That makes domestic homicides an ideal place to look for the effect of sanctuary policies on domestic violence. The results suggest that sanctuary policies are effective for stopping the most severe domestic violence.

In addition, sanctuary policies seem to encourage women to petition for protection under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). VAWA petitions from battered women increased about 2.24 percent because of sanctuary implementation. The researchers in the VAWA study even found some evidence the increase is likely because women are more willing to come forward to report an abuser, in direct contrast to CIS’s claims.

More immigration enforcement results in fewer police calls

We can also step back from considering sanctuary policies specifically and look at what happens when immigrants become more aware of immigration enforcement.

One project used data that combined Google Trends data on immigration-related searches with records on calls to the Los Angeles Police Department from 2014 to 2017. This allowed the researchers, immigration scholars Ashley Muchow and Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, to examine awareness of immigration enforcement in relation to calls to the police department.

Muchow and Amuendo-Dorantes show that calls to the police drop in Latino areas as awareness of immigration enforcement efforts increases. Then when looking at only domestic violence calls they find a similar drop when awareness of immigration enforcement increases. Both of these findings are exactly the chilling effect of immigration enforcement on immigrants’ willingness to call the police—the chilling effect that sanctuary policies are meant to prevent.

CIS’s paper is an interesting contribution to the discussions of relations between immigrants and law enforcement, but it is not enough to overturn the established results of several other studies. This is particularly true as CIS points out two facts in their own work. First, that their data does not allow for discussions of domestic violence, and second that sanctuary policies are often motivated by a concern for preventing domestic violence.

As the CIS researchers acknowledge in their report, the NCVS data does not allow them to come to the conclusion that the basis for sanctuary is a “myth”. There is simply far more evidence in favor of the view that welcoming policies improve both public safety and crime reporting rates.

Smart immigration policy makes everyone safer

None of these findings about crime reporting or the value of sanctuary mean that immigration enforcement should completely end. Instead, they all suggest that heavy-handed enforcement is ineffective and can even backfire on public safety.

For example, a recent study found that a more limited form of ICE-police partnerships can increase reporting rates among Hispanics. Specifically, the study looks at a 2015 policy known as the Priority Enforcement Program. It limited local police and ICE’s collaboration to only serious crimes. The study shows that Hispanics were more willing to report crimes—reporting rates rose by four percent after the priority policy took effect.

Research findings like this are at least part of the reason that President Biden’s administration has shifted the focus of ICE. In the past, many of the immigrants arrested through ICE-police partnerships were not violent threats to public safety. They were people who should be ticketed for rolling through stop signs, speeding, or penalized in a form proportional to the crime.

Enforcement priorities that mirror the Priority Enforcement Program are likely to improve public safety more than throwing a wide net.

With that in mind, the recent drop in ICE’s arrests within the country is a sign of good priorities, not a sign of unguarded or open borders. That reduction happened over the same period as high numbers of apprehensions at the border, after all. So it doesn’t mean that the borders are open.

The broader research on crime reporting and immigration policies suggests that policymakers can protect public safety best by taking a welcoming stance toward immigrants. The few immigrants who are serious threats should be dealt with through targeted enforcement efforts. Placing guard rails around how ICE and local law enforcement cooperate is a sound public safety policy.