Introduction

Immediately upon taking office in 2021, Utah Governor Spencer Cox issued Executive Order 2021-01.1Utah Exec. Order No. 2021-01 ( Jan. 4, 2021). The executive order requires that each licensing agency in Utah conduct a review of occupational licensing requirements and make recommendations on “ways to remove barriers to licensing and limit unnecessary government regulation.”2Ibid. Occupational licensing laws set minimum entry requirements to work and remain in a profession. The requirements include minimum levels of education and training, job experience, passing exams, and paying fees.

Occupational licensing is promoted as a form of consumer protection. By implementing minimum entry requirements for licensed professions, policymakers mean to push low-quality service providers out of the market so that consumers can be sure that they won’t be harmed. For example, in industries where consumers know a lot less than the provider, as is the case with doctors, strict licensing requirements can make sense. They close an information gap between provider and consumer.3Hayne Leland, “Quacks, Lemons, and Licensing: A Theory of Minimum Quality Standards,” Journal of Political Economy 87, no. 6 (1979): 1328–46.

That consumer protection theory of licensing tends to be quite limited in practice, however. Research on licensing’s actual effects has shown that many licensing laws are better thought of as industry protection.4Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962). In the summer of 2015, the Obama White House released a report summarizing what is known about the effects of occupational licensing.5US Department of the Treasury Office of Economic Policy, the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA), and the Department of Labor, Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers, July 2015. The results of the report can be summarized as follows:

- Licensing results in a wage premium of between 10 and 15 percent for licensed workers.

- Licensing reduces total employment in the licensed profession. A more recent study estimates that this reduction is between 17 and 27 percent.6Peter Blair and Bobby Chung, “How Much of a Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing?,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (2019): 919–43.

- Licensing increases the price of services by between 3 and 16 percent.

- Existing evidence of the effects of licensing on service quality is ambiguous at best. Another recent study finds that 20 percent of the increase in prices and 40 percent of the increase in wages coming from licensing result in no measurable benefit to consumers and workers respectively.7Morris M. Kleiner and Evan J. Soltas, “A Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing in US States” (Staff Report 590, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, October 2019).

In short, instead of protecting consumers, occupational licensing often creates a barrier to entry that reduces market competition. When this happens, this regulatory tool often results in more costs than benefits.

The question for policymakers is then how to determine when licensing makes sense and when other policy tools would better protect consumers. Unfortunately, licensing has become a default solution rather than something to be used sparingly in cases where there is an obvious failure of private markets. In 1950, just 5 percent of the nation’s workers were licensed. That is now greater than 20 percent—more than a fourfold increase.8Morris Kleiner, Licensing Occupations: Ensuring Quality or Restricting Competition? (Kalamazoo, MI: W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2006).

Like every other state in the United States, occupational licensing is prevalent in Utah. Recent estimates suggest that just over 16 percent of workers in Utah are licensed.9Morris Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov, At What Cost? State and National Estimates of the Cost of Occupational Licensing (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, 2018), https://ij.org/report/at-what-cost.

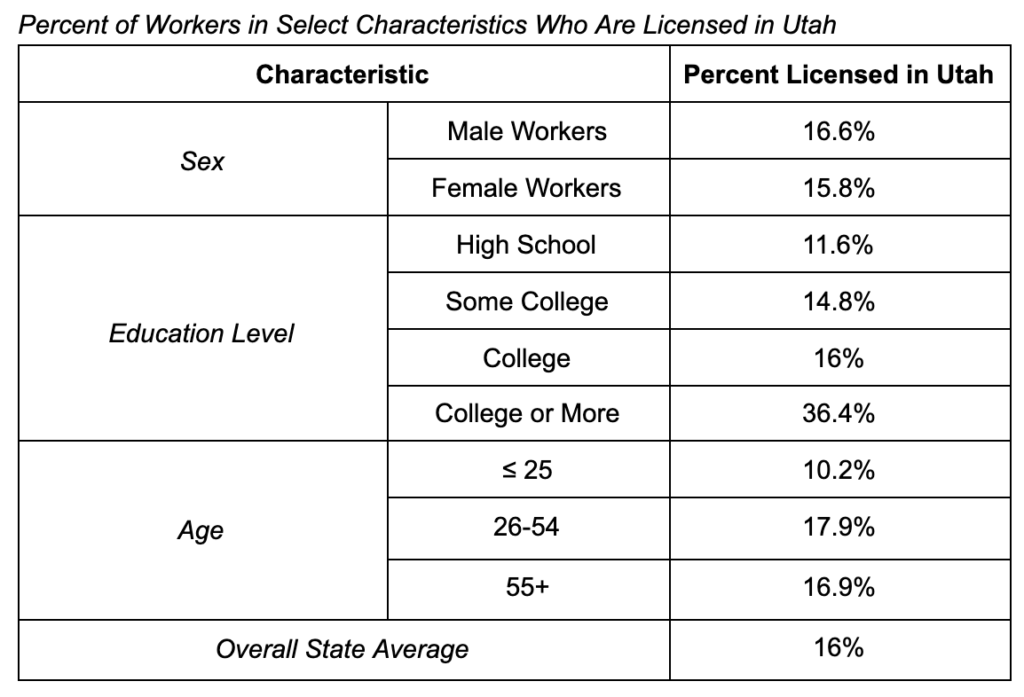

Table 1 provides more details regarding the fraction of workers licensed in Utah, broken down by various worker characteristics. Licensing is much more prevalent for workers with higher levels of education. This is not surprising—licensing often stipulates that workers complete minimum levels of education. It is nevertheless interesting to explore differences in licensing attainment across differences in educational attainment. More than 36 percent of Utah workers with education beyond a college degree, such as lawyers and doctors, are licensed. Nearly 18 percent of prime-age workers in Utah are licensed.

Table 1. Percent of Workers in Select Characteristics Who Are Licensed in Utah

Source: Morris Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov, At What Cost? State and National Estimates of the Cost of Occupational Licensing (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, 2018), https://ij.org/report/at-what-cost.

In this brief, we first introduce a framework for evaluating licenses and determining when licensing is the appropriate policy response. The framework is meant as a guide for determining when to remove existing but unnecessary licenses, as well as what to license in the future. Second, we compare requirements for four licensed occupations in Utah to those in surrounding states. These occupations are associate real estate brokers, real estate sales agents, cemetery salespersons, and genetic counselors.

The framework we introduce for evaluating licenses provides a general pathway for determining the optimal policy response. Our framework makes clear the value of exploring and using alternatives to licensing. In many cases, licensing is the default when it should be supplanted by other types of labor market regulation.

The occupations evaluated were specifically chosen to highlight instances where Utah’s occupational licensing requirements stand out as stricter than those of its neighbors. We compare licensing requirements in Utah to the bordering states of Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, and Wyoming. Our comparison yields insights into where Utah’s licensing requirements are perhaps more stringent than necessary. This comparison is not exhaustive; rather, it is meant to serve as a starting point for regulatory reform.

Our general approach is consistent with principles from Governor Cox’s executive order, including that “excessive regulation creates barriers to working” and “government should impose only those regulations that are necessary to protect the health, safety, and well-being of Utah residents.”10Utah Exec. Order No. 2021-01 ( Jan. 4, 2021).

A Guiding Principle for Licensing Reform: Consumers First

Our formal blueprint for a successful review process of occupational licensing in Utah starts with a focus on the consumer. The stated purpose of licensing from regulators and professional associations is to protect consumers from harm. We therefore take the perspective that licensing laws should be evaluated based on the effects that licensing has on consumers, rather than the effects it has on industry participants.

Recent research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis shows that, overall, licensing has become a net cost to consumers.11Kleiner and Soltas, “A Welfare Analysis.” Even workers lose out, according to the research, because only about 60 percent of the costs of earning a license are recouped through higher wages. Even after accounting for increases in quality resulting from licensing, the research shows that licensing on net harms consumers. This is an aggregated study looking at the entire “regulatory thicket” that workers must pass through to obtain an occupational license. The study’s fundamental contribution is simply that licensing is an overall loss for the economy.

Another recent study, from the Institute for Justice, has estimated the effect of occupational licensing on Utah’s workers and economy. The authors find that licensing results in more than 19,000 fewer jobs being created and a deadweight loss of nearly $88 million each year.12Kleiner and Vorotnikov, At What Cost? Taken together, these findings cast doubt on whether the expansion of licensing is benefiting consumers.

One approach to judging policies states that regulators should prefer the least burdensome type of regulation that accomplishes stated consumer protection goals. The Institute for Justice outlines a number of policy options between the least restrictive means of regulation (i.e., market competition) and the most onerous (i.e., occupational licensing).13John Ross, The Inverted Pyramid (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, 2017), https://ij.org/report/the-inverted-pyramid/. Both Arizona14Starlee Coleman, “Arizona Becomes First State in Country to Protect the Right to Earn a Living,” Goldwater Institute, April 6, 2017, https://goldwaterinstitute.org/article/arizona-becomes-first-state-in-country-to-protect-right-earn-living/. and Tennessee15S. 2469, Tenn. Pub. Ch. No. 1053 (Tenn. 2016). provide examples of how to implement this type of reform in practice, as each has passed a Right to Earn a Living Act. The legislation allows aspiring workers to sue the state if they believe occupational licensing laws are infringing on their basic right to work. The onus then falls upon the state to document the harm that is being reduced from existing licensing laws.

Similarly, if professional associations lobby for licensing legislation, the burden should be placed upon the association to document harm to consumers that will occur without the desired regulation. Professional associations should also be required to document why another type of regulation is insufficient. For example, sometimes market competition is enough to discipline poor-quality providers—they will not be in business for very long if they receive enough negative reviews. Recent research shows that consumers are much more interested in online reviews of contractors than they are in licensing attainment.16Chiara Farronato, Andrey Fradkin, Bradley Larsen, and Erik Brynjolfsson, “Consumer Protection in an Online World: An Analysis of Occupational Licensing” (NBER Working Paper No. 26601, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, January 2020). As an additional example, automobile mechanics are regulated via a private certification body as well as through market reputation.

Barbers and cosmetologists are two examples of professions where an overly strict regulatory framework might be in place. Service providers in these professions are licensed in all 50 states.17In the United States, Alabama did not license barbers at the state level from 1983 to 2013. See Edward Timmons and Robert Thornton, “There and Back Again: The De-licensing and Re-licensing of Barbers in Alabama,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (2019): 764–90. Yet the United Kingdom does not license either profession.18In fact, half of EU members do not license barbers or cosmetologists. European Commission, Regulated Professions Database, accessed May 1, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regprof/index.cfm?action=profession&id_profession=12019.

Utah has already made some progress at licensing reform over the last five years. In 2020, the state passed a form of universal recognition, meaning out-of-state licenses will generally be accepted in Utah.19Utah State Legislature, “S.B. 23 Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing Amendments,” accessed April 27, 2021, https://le.utah.gov/~2020/bills/static/SB0023.html. In 2017 Utah significantly scaled back licensing requirements for all contractor occupations and mobile home installers.20Dick M. Carpenter II, Lisa Knepper, Kyle Sweetland, and Jennifer McDonald, “Update Details,” License to Work, Institute for Justice, February 22, 2018, https://ij.org/report/license-work-2/updates/. “H.B. 313 changed the licensing requirements for various contractor occupations and mobile home installers, effective May 9, 2017. Fees decreased to between $210 and $445. Two years of experience eliminated. Education increased to 25 clock hours. Exams eliminated.” Both of these reforms have made Utah a state where it is easier for people to make a living. Licensing, nonetheless, continues to provide significant costs to consumers and aspiring workers in the state without sufficient benefit to justify its application in some instances. The next step for the state should be a thorough review of its licenses and licensing procedures to continue making progress.

Performing a Review: A Three-Step Process

We now turn to a framework for a successful and meaningful review of licensing legislation. A review process should be informed by the best available evidence and inspire a culture of evidence-based policy within a state. To that end, we propose a three-step process. First, regulators should compare Utah’s licensing laws to other states. Second, Utah should implement a Fresh Start initiative. And third, the state should create a robust sunrise review process.

Step 1. How Does Utah Compare?

In determining where to concentrate reform efforts, Utah should begin by conducting a review of its existing licensing laws, with the goal of comparing these laws to those found in other states. As noted above, this should only serve as a starting point. There are many instances (e.g., barbers and cosmetologists) where licensing is universal in all states, but hard to justify.

In practice, reviewing licensing laws in this way requires significant investment. Depending on the degree of investment Utah policymakers want to make, there are two relevant comparison groups for a licensing review: compare Utah to all US states and jurisdictions; or, if too cumbersome, compare Utah’s licensing requirements to bordering states.

A comprehensive 50-state review approach is generally better, at least in theory, but it is also more demanding. A database from the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation contains data for more than 400 occupations, but this list of 400 occupations is not comprehensive of all occupations. In instances where freely available databases do not contain the relevant licensing requirements, or when time does not permit looking up individual laws for each of the 50 states, it can save time to compare Utah’s licenses to those in its six neighbor states.

Step 2. A Fresh Start for Utah

After the initial comparison is completed (step 1), the state should move forward with reforming problematic regulations (step 2). In a previous policy paper, the Center for Growth and Opportunity provided the framework for a Fresh Start initiative.21Conor Norris, Josh Smith, and Edward Timmons, “How to Reform Occupational Licensing” (Policy Paper 2020.011, Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, Logan, UT, December 2020), https://www.thecgo.org/research/how-to-reform-occupational-licensing/; Patrick A. Mclaughlin, Matthew D. Mitchell, and Adam Thierer, “How to Create a Fresh Start Initiative in Your State: A Step-by-Step Guide” (Mercatus Policy Spotlight, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, May 2020). An independent commission could be established that has the authority to order the removal of unnecessary licensing regulation. The independent commission could make a set of recommendations based on the prior review, and the Utah legislature could have a simple up or down vote on the entire package of regulatory reforms with no possibility of individual consideration of the recommendations. If policymakers affirm the reform recommendations, the committee could dissolve for an established time period (e.g., three years) before conducting another round of reviews and recommendations.22This initiative has many things in common with recent reform efforts in states like Mississippi. James Broughel and Patricia Patnode, “Taming the Occupational Licensing Boards and Creating Jobs,” Discourse, February 10, 2021, https://www.discoursemagazine.com/economics/2021/02/10/taming-the-occupational-licensing-boards-and-creating-jobs/. If policymakers vote the recommendations down, the committee could have the ability to issue a new set of recommendations for legislators to consider. A Fresh Start program as described provides a clear pathway for recommendations to be considered by legislators, which gives it an advantage over some other forms of review procedures.23Robert J. Thornton and Edward J. Timmons, “The De-licensing of Occupations in the United States,” Monthly Labor Review, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 18, 2015, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/the-de-licensing-of-occupations-in-the-united-states.htm.

When asking if the state is getting the regulations right, regulators could be asked to conduct a basic cost-benefit analysis. Anecdotes of offenses that cannot be directly attributable to regulation are insufficient as justifications. Rather, evidence should be presented that a real problem exists in the labor market and that the problem is systemic, rather than anecdotal. Moreover, it should be clearly indicated why licensing improves outcomes for consumers instead of making things worse.

It is also reasonable to question the form of regulation. In each case, regulators should ask themselves a series of basic questions. What evidence is there that licensing is the best shield for consumers in this occupation? Could licenses be replaced with safety training? Can requiring that practitioners carry insurance be a better solution to prevent harm to consumers than licensing? Why don’t existing laws against fraud adequately serve to protect consumers and give them recourse when they are harmed? How would a titling or registration policy compare to licensing this occupation? In answering each of these questions, the rules should reflect a reasonable chain of logic from a problem on the ground to a clear solution that protects consumers. If the current level of regulation cannot be clearly justified, a plan should be made for amending or removing the unnecessary regulation.

Step 3. Going Forward: Sunrise Review

After conducting a review and modifying or removing occupational licenses if necessary with a Fresh Start program, it is important that a state not return to business as usual. Once licensing is in place, it has generally proven very difficult to remove.24Thornton and Timmons, “De-licensing of Occupations.” Given that licensing is not always as effective as it should be at protecting consumers, it is critical that licensing laws put in place can be justified on the basis of sound evidence. To ensure this is the case, new licensing initiatives should be subject to independent review.

Several states, including bordering state Colorado, have a sunrise review process. From 1985 to 2005, sunrise review helped Colorado limit new regulation, adding it in only 19 of 109 submitted proposals.25Bruce Harrelson, “Colorado’s Sunrise Review” (letter to the editor), Regulation, Winter 2006/2007, 2, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2006/12/v29n4-record.pdf. Professional associations or other groups that seek licensure should be required to document how consumers are harmed by the current regulatory regime, and legislators should follow the principle of using the least restrictive regulatory means of protecting consumers. That’s because licensing can all too easily end up benefiting incumbent industries at the expense of consumers and aspiring workers. Once a licensing board is captured by the interest groups it regulates, it can be onerous and contentious to remove licenses, even those that are obviously not achieving their intended goals.26Thornton and Timmons, “De-licensing of Occupations.” As outlined previously, policymakers should always put the general public’s interests first rather than cater to the private gain of a special interest group.

Comparing Four Licensing Requirements in Utah to Bordering States

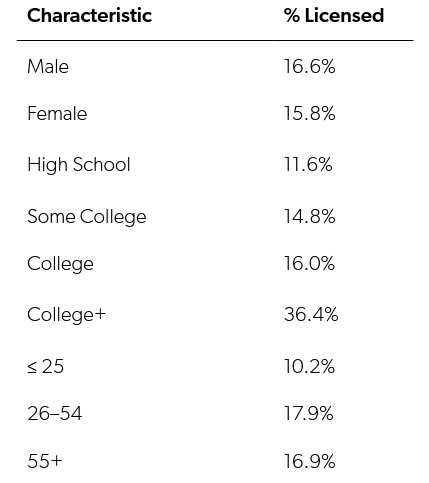

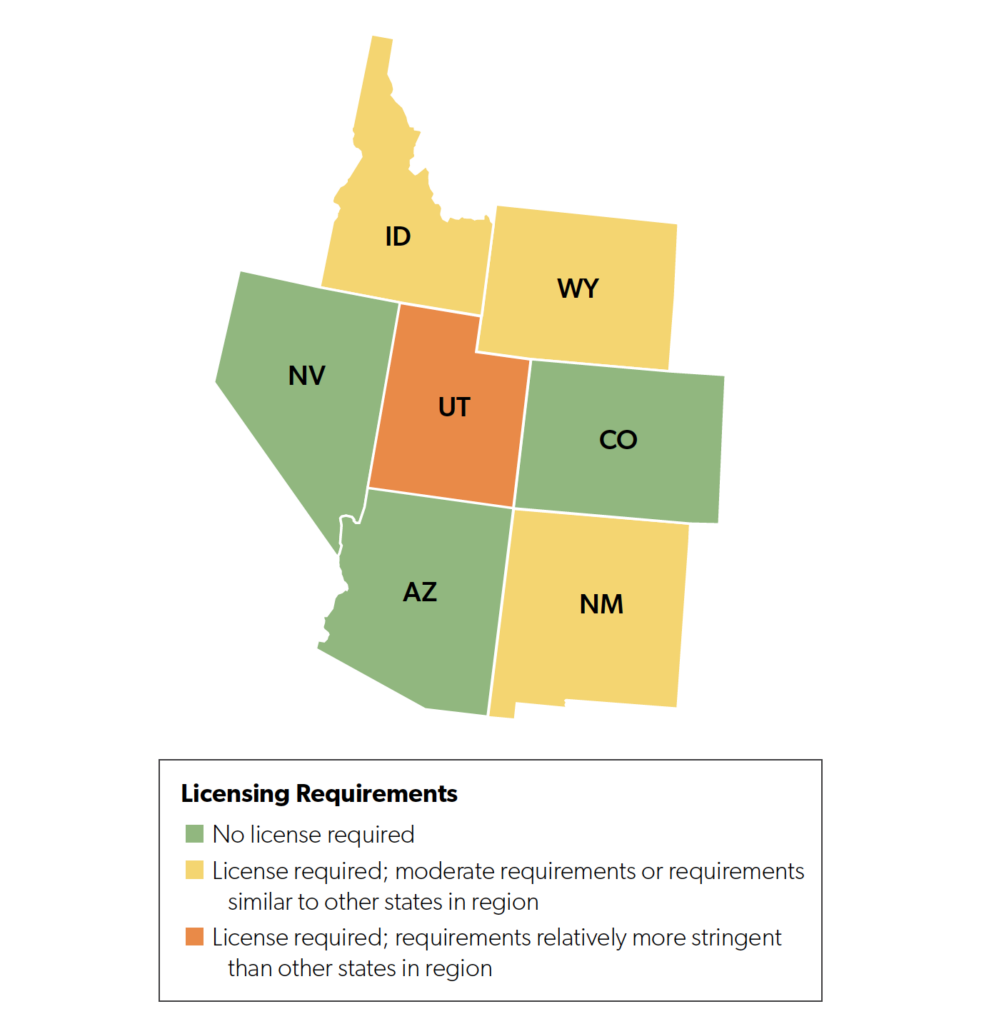

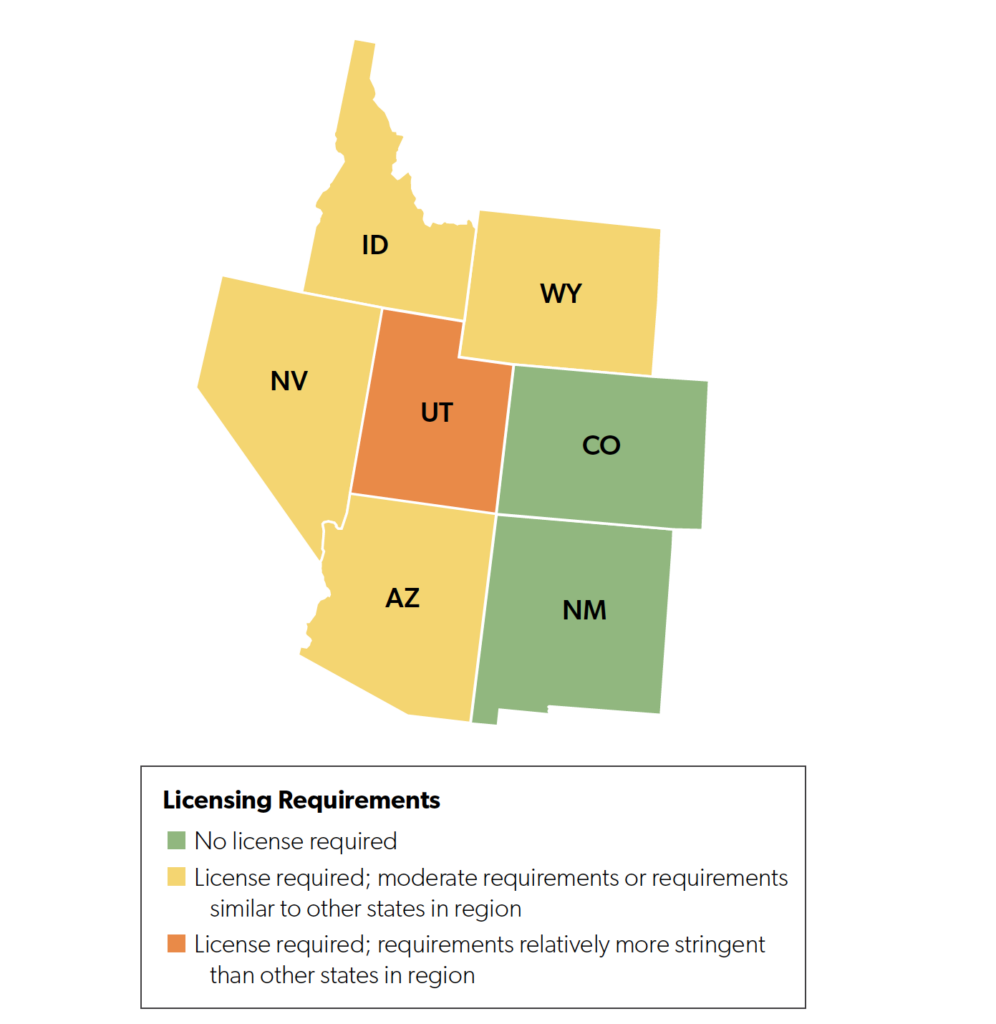

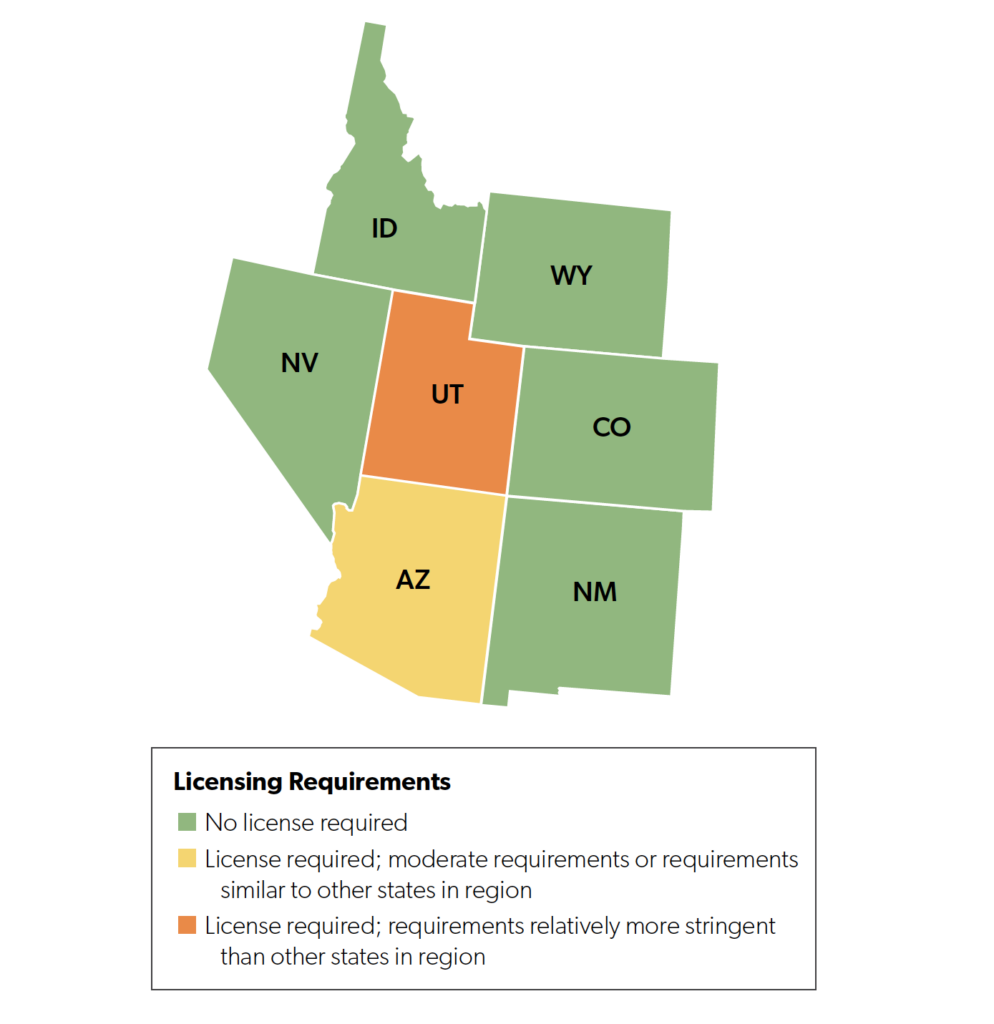

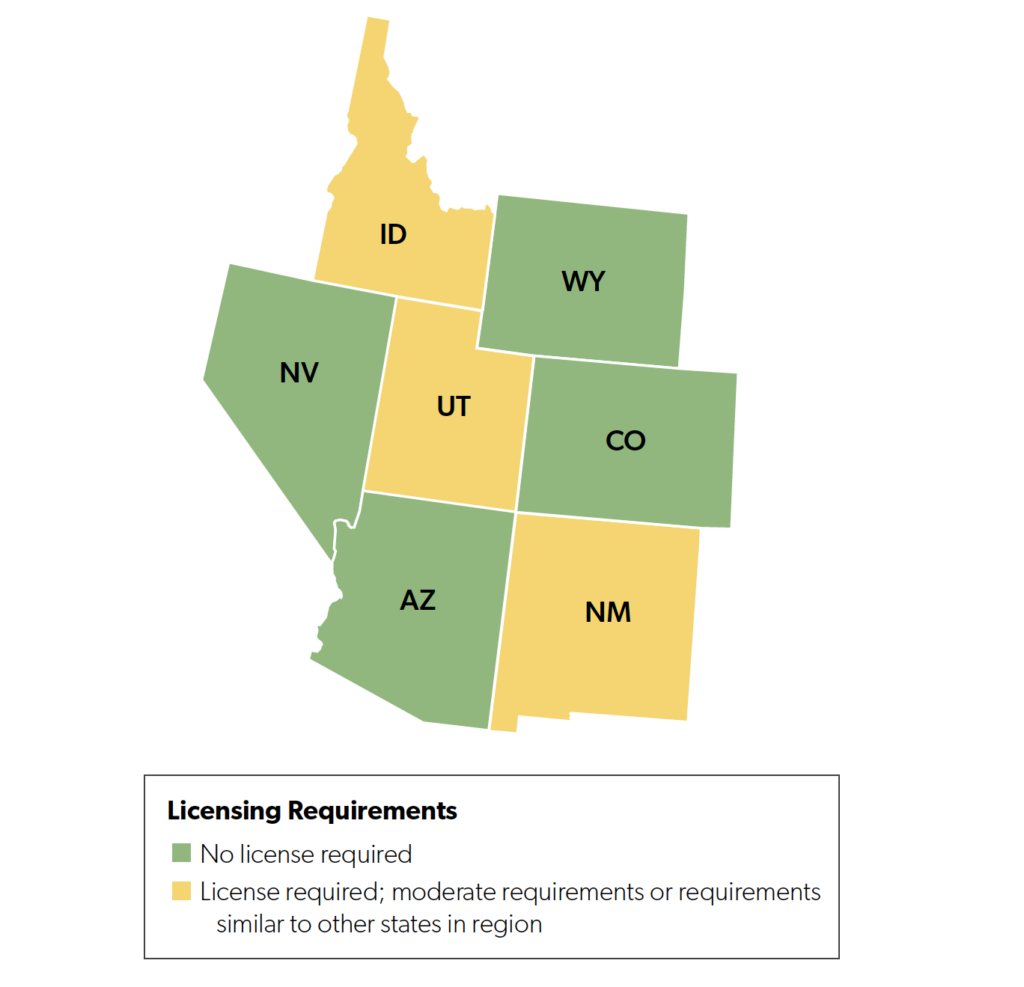

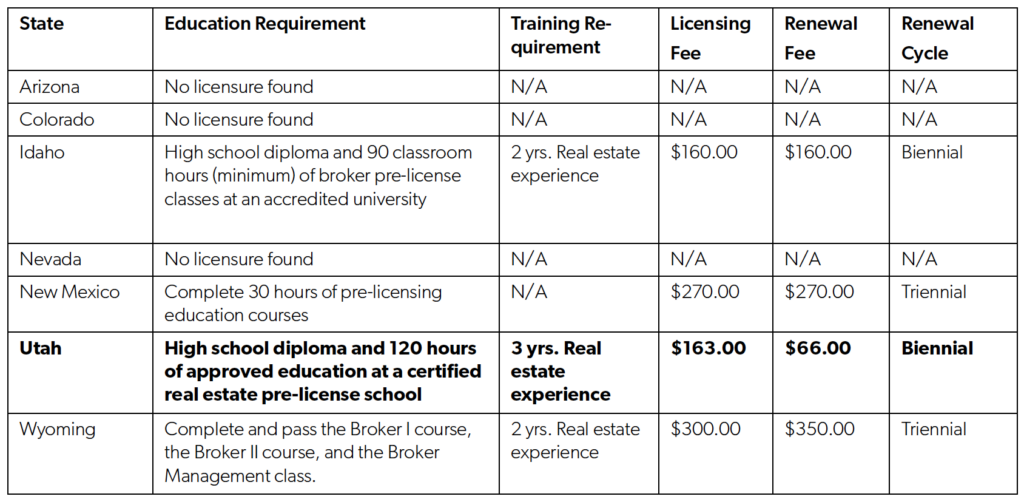

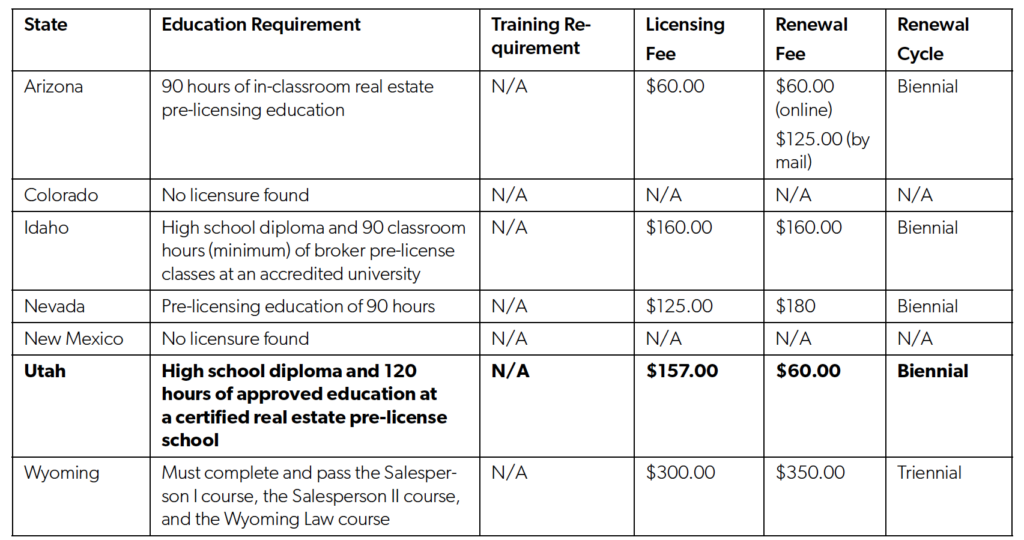

In this section, we compare the licensing regimes for four select professions in Utah to the regimes found in Utah’s neighboring states of Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. We use orange shading to denote stringent licensing requirements, yellow for moderate licensing requirements or licensing requirements that are similar to comparison states, and green if a state does not license the profession. Readers interested in exploring more detailed comparisons of the licensing requirements for these professions in Utah, as well as its surrounding states, are referred to appendix 1, which draws from a database compiled by the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation on occupational licensing requirements for all 50 states and the District of Columbia.27The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulations database can be accessed at https://csorsfu.com/find-occupations/.

Associate Real Estate Brokers

Associate brokers are under the employment, management, and supervision of a licensed principal broker in the business of selling real estate. Figure 1 illustrates how licensing requirements vary for this profession across Utah and its neighboring states. Arizona, Colorado, and Nevada do not license associate brokers.28We should note here that this does not imply that licensing does not penetrate the sale of real estate in these three states. We chose to focus on associate brokers here to highlight discrepancies in Utah. Compared to bordering states that do license the profession, Utah has relatively stringent education requirements (120 hours) and the most stringent experience requirements (3 years).29Utah Admin. Code r. 61-2f (2021). For comparison, Idaho requires 90 hours of education and New Mexico requires only 30 hours of education.30Idaho Code § 54-20 (2021); N.M. Stat. § 61-29 (2021). Idaho and Wyoming require only 2 years of experience.31Wyo. Stat. § 33-28 (2021).

Figure 1. Comparison of Licensing Requirements for Associate Real Estate Brokers

Real Estate Sales Agents

Our next comparison focuses on real estate sales agents and is illustrated in figure 2. A real estate sales agent is an employee under a principal broker and aids in the process of buying and selling real estate. Sales agents do not require as much experience to begin working as associate real estate brokers discussed above. Colorado and New Mexico do not license real estate agents. Among the five states in the region that do license real estate sales agents, Utah has the most stringent requirements. Utah requires aspiring real estate sales agents to complete high school and 120 hours of additional education.32Utah Admin. Code r. 61-2f (2021). Idaho also requires a high school diploma but requires only 90 hours of additional education.33Idaho Code § 54-20 (2021). Arizona, Nevada and Wyoming do not require a high school diploma but do require 30-90 hours of additional education.34Nev. Admin. Code § 645 (2021); Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 32-2124 (2021); Wyo. Stat. § 33-28 (2021).

Figure 2. Comparison of Licensing Requirements for Real Estate Sales Agents

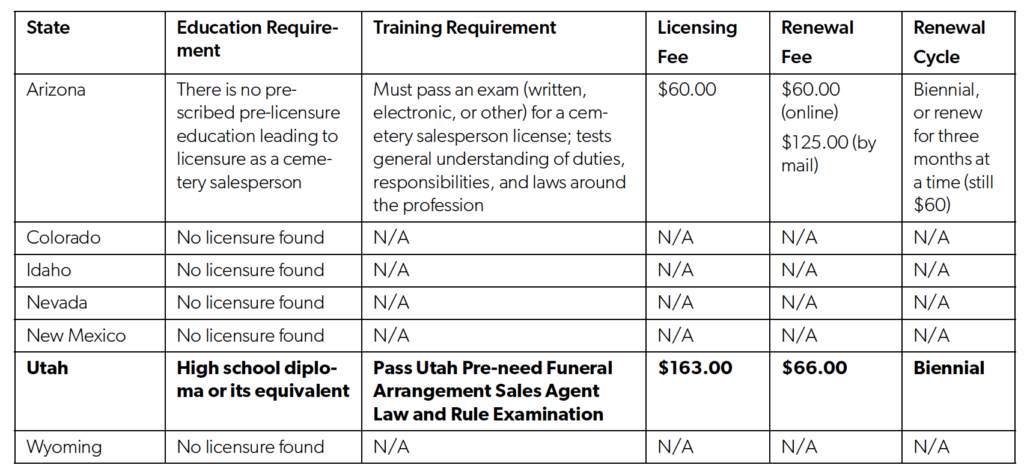

Cemetery Salespersons and Pre-need Funeral Arrangement Sales Agents

Next, we compare requirements for cemetery salespersons and pre-need funeral arrangement sales agents. Workers in these occupations sell funeral goods and services. Figure 3 illustrates our regional comparison of licensing requirements for this profession. Utah and Arizona are the only two states in the region that license this profession. Utah requires aspiring cemetery salespersons to complete high school, while Arizona has no minimum education requirement.35Utah Admin. Code r. 58-9 (2021); Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 32-2124 (2021).

Figure 3. Comparison of Licensing Requirements for Cemetery Salespersons and Pre-need Funeral Arrangement Sales Agents

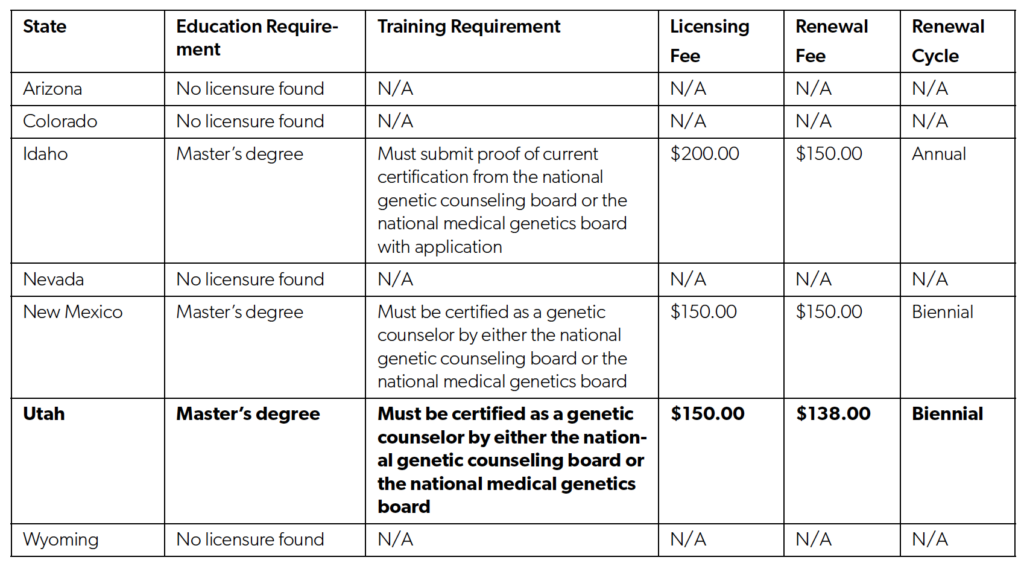

Genetic Counselors

The final occupation that was assessed is genetic counselors, depicted in figure 4. Genetic counselors provide information about possible genetic conditions to families through genetic testing. Since 2002, Utah has required genetic counselors to have a license to practice.36Utah Admin. Code r. 58-75-3 (2021). Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and Wyoming do not license genetic counselors.37The licensing of genetic counselors in Colorado was avoided in 2019 via veto by Governor Jared Polis. John Frank, “Why Jared Polis Vetoed 5 Bills, and What It Could Mean for Thousands of Licensed Professionals in Colorado,” Colorado Sun, June 3, 2019, https://coloradosun.com/2019/06/03/jared-polis-veto-occupational-licenses/. Idaho, New Mexico, and Utah all require aspiring genetic counselors to obtain master’s degrees and pay fees to the state to obtain a license to begin working.38Idaho Code § 54-5605 (2021); 16 N.M. Admin. Code 16.10.21 (2021); Utah Admin. Code r. 58-75-3 (2021).

Figure 4. Comparison of Licensing Requirements for Genetic Counselors

Conclusion

Occupational licensing can make sense as a policy tool. But first, policymakers should carefully weigh the costs and benefits of licensing against the costs and benefits of alternative policies. As noted above, research has shown that occupational licensing does not always benefit consumers or aspiring workers, but instead often creates market inefficiencies and benefits incumbents within an industry at the expense of consumers. These costs are well documented and estimates suggest that the status quo is costing Utah more than 19,000 jobs and almost $88 million a year in lost economic activity.

We provide a small sample of what the first step of a successful review process should look like in the preceding section. However, just because another state has adopted a policy does not mean the policy is the best way forward. For example with barbering, all 50 states require licensing, but it is far from clear that licensing is the best regulatory option. Therefore, these state-by-state comparisons should be seen as a starting point, which can then be followed by a robust Fresh Start initiative and sunrise review process.

This policy brief has provided a framework for establishing a regulatory review system built for the long haul. Moving forward with the three-step process outlined above could allow Utah to emerge as the nation’s leader on licensing reform. Reforms like these can mean lower prices for consumers, more employment opportunities for workers, and a more robust Utah economy, all without sacrificing the quality of services provided to Utah citizens.

Appendix

Table A1. Associate Real Estate Brokers

Source: The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation, CSOR Occupational Regulation Database> (database), accessed April 25, 2021, https://csorsfu.com/find-occupations/.

Table A2. Real Estate Sales Agents

Source: The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation, CSOR Occupational Regulation Database> (database), accessed April 25, 2021, https://csorsfu.com/find-occupations/.

Table A3. Cemetery Salespersons and Pre-need Funeral Arrangement Sales Agents

Source: The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation, CSOR Occupational Regulation Database> (database), accessed April 25, 2021, https://csorsfu.com/find-occupations/.

Table A4. Genetic Counselors

Source: The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation, CSOR Occupational Regulation Database> (database), accessed April 25, 2021, https://csorsfu.com/find-occupations/.