Introduction

Occupational licensing laws affect nearly one-quarter of all workers, which is far greater than other labor-market institutions, such as unions or minimum wage laws.1“Data on certifications and licenses,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2020 https://www.bls.gov/cps/certifications-and-licenses.htm These laws are intended to promote consumer safety by limiting those working in licensed fields to only those who can meet the required skill-level and training requirements. However, because licensing laws act as a barrier to entry, they reduce the supply of professionals in licensed fields. That, in turn, increases prices and reduces access for consumers. Occupational licensing requirements also make it more difficult for professionals to move between states.

State-level requirements that act as limitations on where licensed professionals can practice became an immediate challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, regulators temporarily welcomed health care workers from out of state in addition to lifting other licensing restrictions.2Ethan Bayne, Conor Norris, and Edward J. Timmons, “A Primer on Emergency Occupational Licensing Reforms for Combating COVID-19,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, March 26, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/covid-19-policy-brief-series/primer-emergency-occupational-licensing-reforms-combating. Although temporary, these changes present a valuable opportunity to consider occupational licensing reforms such that the regulatory regime ensures consumer safety at lower economic cost.

Reforms Congress and state policymakers should consider include establishing a commission to evaluate whether to extend the temporary changes beyond the time of crisis, establishing sunset commissions to regularly review licensing laws, implementing universal recognition, and requiring states to revise licensing laws such that they are not more onerous than other states’ laws.

Measures to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 have caused significant economic hardship. Given that reality, removing barriers to entry is even more important to help people return to work and make the economy more flexible and resilient in the face of COVID-19.

In this policy brief, we examine the effects of occupational licensing, review the reforms states have temporarily enacted, and consider reforms that state lawmakers and Congress should adopt to reduce the costs of occupational licensing and make state economies more resilient to future shocks.

Background on Occupational Licensing

Occupational licensing laws are passed by states to regulate who may enter and practice in a profession. These laws mandate minimum qualifications for beginning work, which must be met before an aspiring worker may practice. Professionals are required to reach minimum levels of education and training, pass exams, and meet a variety of other requirements.

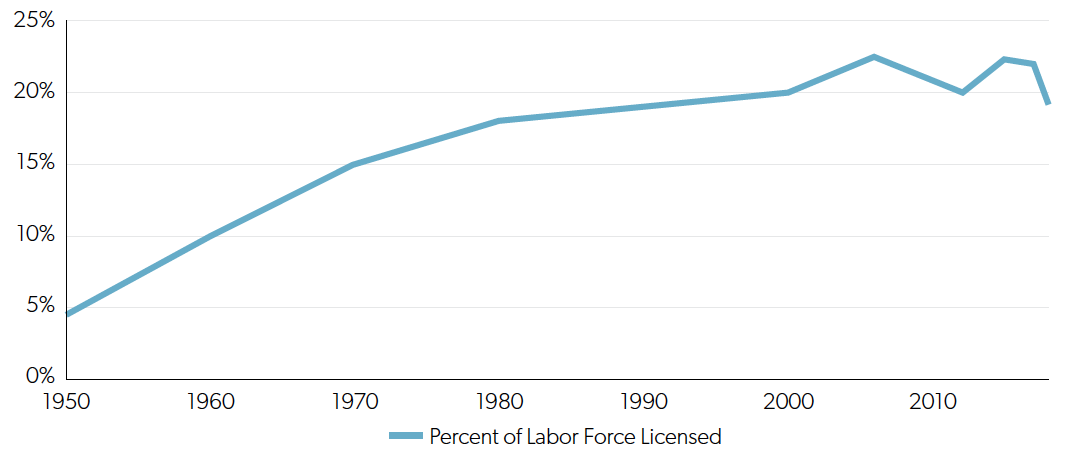

Over time, the percentage of the labor force that requires a license has increased considerably. In the 1950s, around 5 percent of the workforce needed a license to work. Today, about 20 percent does.3Josh T. Smith, Vidalia Freeman, and Jacob M. Caldwell, “How Does Occupational Licensing Affect U.S. Consumers and Workers?” Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, December 2018, https://www.thecgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/how-does-occupational-licensing-afect-US-consumers-and-workers.pdf?_ga=2.72426963.1963643269.1588009010–269371620.1587567574. Licensing affects workers more than other institutions that regulate labor markets. For instance, just 10 percent of workers belong to a labor union.4“Union Members Summary,” accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm. Meanwhile, less than 2 percent of the labor force receives the minimum wage.55 “Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers, 2019,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 2020, https://www.https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2019/home.htm.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm. Figure 1 shows a series of estimates of the percentage of workers that require a license. The fall after the 2008 peak does not represent liberalization of licensure. Instead, it is a result of different methodologies of tabulating the fraction of licensed workers before the Current Population Survey added questions on licensing status.

Figure 1: The licensed share of the US labor force (1950–2018)6Adapted from Smith, Freeman, and Caldwell, “Occupational Licensing.”

The purpose of occupational licensing is to protect consumers by providing a minimum level of quality. However, research is mixed on whether licensing improves quality.7“Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers,” White House, July 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/licensing_report_final_nonembargo.pdf; Chiara Farronato, Andrey Fradkin, Bradley Larsen, and Erik Byrnjolfsson, “Consumer Protection in an Online World: An Analysis of Occupational Licensing,” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 3, 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26601.pdf. While it does prevent low quality professionals from entering the profession, it also reduces competitive pressure,8Conor Norris and Edward Timmons, “Restoring Vision to Consumers and Competition to the Marketplace: Analyzing the Effects of Required Prescription Release,” Journal of Regulatory Economics 57 (2020): 1–19. the losses from which may swamp the gains from preventing low-quality professionals from entering.

Licensing laws represent barriers to entry that prevent people who lack the time to meet the requirements or lack the savings needed to delay the start of their career. This disproportionately impacts lower-income workers by preventing them from switching to higher-paying jobs or jobs in growing industries.9Matthew Mitchell, “Occupational Licensing and the Poor and Disadvantaged,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, September 28, 2017, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/corporate-welfare/occupational-licensing-and-poor-and-disadvantaged#:~:text=Because%20many%20licensed%20professionals%20offer,the%20form%20of%20higher%20prices.&text=The%20high%20costs%20of%20licensing,out%20of%20the%20childcare%20market. Economists Peter Blair and Bobby Chung find that licensing laws reduce the labor supply between 17 and 27 percent.10Peter Blair and Bobby Chung, “How Much of Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing?” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (May 8, 2019): 919–43. For professions that are partially licensed, Morris Kleiner estimates that employment in licensed states grows 20 percent slower than employment in unlicensed states.11Morris M. Kleiner, Licensing Occupations: Ensuring Quality or Restricting Competition? (Upjohn Press, 2006). Kleiner and Evan Soltas show that licensing reduced the number of professionals by 11 percent across a wider array of professions than Kleiner’s earlier study.12Evan J. Soltas and Morris M. Kleiner, “Occupational Licensing, Labor Supply, and Human Capital,” May 2018, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ad29/a137c7dd68f890bbf1e9beeec6d3c1114523.pdf.

Because licensing restricts the supply of professionals, it also increases their earnings. Kleiner and Kudrle find that stricter licensing requirements were associated with an earnings premium.13“Does Regulation Affect Economic Outcomes? The Case of Dentistry on JSTOR,” accessed May 1, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.1086/467465.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ab0b05511bcdf9176d3f53b98c99af043. Across licensed professions, licensing is associated with an 11 percent wage premium. These higher wages translate to higher prices for consumers.14Morris M. Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov, “Analyzing Occupational Licensing among the States,” Journal of Regulatory Economics 52, no. 2 (October 19, 2017): 132–58. Supporters of licensing argue that because licensed professionals earn higher income in a licensed market than in a market with free entry, the opportunity cost of poor performance is greater, which should reduce shirking and increase quality. However, as noted, there is limited evidence that licensing laws improve quality.15Occupational Licensing,” White House.

Licensing laws are passed at the state level, making it difficult to transfer licenses between states. State licensing boards typically require professionals moving to their state to meet all of the state requirements. This forces professionals to go through the license-application process again, including taking exams and paying fees required by the state, after having already demonstrated their quality in their previous state. These additional costs and delays are associated with a reduction in the interstate mobility of licensed workers of as much as 36 percent.16Janna E. Johnson and Morris M. Kleiner, “Is Occupational Licensing a Barrier to Interstate Migration?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, accessed May 1, 2020, doi:10.1257/pol.20170704.

Licensing laws in health care include scope-of-practice provisions, which detail the tasks that professionals are able to perform as a part of their job. While their purpose is to ensure patient safety and high-quality care from knowledgeable professionals, such provisions often prevent professionals from performing tasks that they have the education and training to perform. This reduces the availability of care for patients.17Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine, “Key Messages of the Report,” in The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (National Academies Press, 2011). In addition, such rules can protect members of the occupation from competition from new entrants into the profession. Multiple studies of licensing show that there is no change in quality when scope-of-practice laws change, and some even show an increase in some quality measures.18Patrick McLaughlin, Matthew D. Mitchell, and Anne Philpot, “The Effects of Occupational Licensure on Competition, Consumers, and the Workforce,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, November 3, 2017, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/corporate-welfare/effects-occupational-licensure-competition-consumers-and-workforce.

Occupational licensing also creates economic costs. Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov estimate that the US economy would have two million more jobs without licensing. In addition, the national economy would be at least $6 billion larger.19Evgeny Vorotnikov and Morris M. Kleiner, “At What Cost?” Institute for Justice, November 2018, https://ij.org/report/at-what-cost/. Growth in licensing has also been linked with reductions in economic mobility and increases in income inequality.20Brian Meehan, Edward Timmons, Andrew Meehan, and Ilya Kukaev, “The Effects of Growth in Occupational Licensing on Intergenerational Mobility,” Economics Bulletin 39, no. 2 (2019): 1516–28.

The threat of new entrants keeps prices low and forces incumbents to improve their products. Licensing laws prevent entrepreneurs from starting new businesses. This stifles the product innovation that better meets consumer needs.

Temporary COVID-19 Reforms

As COVID-19 spread across the United States, the typical costs associated with licensing laws were made more visible and were exacerbated. Occupational licensing laws limit the supply of health care professionals under normal circumstances. The United States faces a shortage of physicians that is projected to grow.2121 IHS Markit, “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2017 to 2032: 2019 Update,” Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019, https://www.aamc.org/system/files/c/2/31-2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Additionally, the health care industry faces a persistent shortage of nurses.2222 Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011). Shortages are concentrated in rural areas and low-income urban areas. The limited number of physicians increases wait times for patients seeking care and makes it more difficult to get treatment. It also limits the number of facilities and reduces the capacity of existing facilities. The difficulty of getting care encourages patients to delay treatment, worsening their health outcomes.

As noted, the difficulty of transferring a license to another state decreases worker movement between states. This makes the supply of health care professionals less responsive to changing regional needs over time. Absent licensure, a shortage of professionals in an area should lead to more professionals moving there. However, licensing laws make moving more expensive and time-consuming.23Janna E. Johnson and Morris M. Kleiner, “Is Occupational Licensing a Barrier to Interstate Migration?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12, no. 3 (2020), 347–73, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20170704.

As noted, in many states scope-of-practice laws prevent professionals from performing tasks that they are qualified and trained to perform. This also makes it more difficult to solve regional shortages. If professionals like nurse practitioners and physician assistants were able to practice to the full extent of their training, they could provide some of the services of physicians, which in turn would allow physicians to focus more on treatments that only they are trained to perform, allowing them to serve more patients.

These effects of occupational licensing combine to make responding to COVID-19 more difficult. Health care shortages, which in times of normal demand harm patients, make treating COVID-19 patients more difficult. In areas that suffered severe outbreaks, hospitals were overrun with patients and lacked the resources to meet the sudden surge in demand. Places that struggled to meet the demand from COVID-19 patients, such as Lombardy (Italy) and New York City, are relatively well off. Many other areas have far fewer resources and health care professionals. The risk of a COVID-19 outbreak overwhelming these areas is even greater.

The difficulty of transferring licenses between states prevents the movement of health care professionals to places that need support to fight outbreaks. This forces shortage areas to make do with limited resources. And in many states, some of those resources, skilled health care professionals, are not able to use their training to treat patients.

Because occupational licensing laws limit health care capacity, many states enacted temporary measures relaxing licensing requirements to combat COVID-19. These temporary waivers gave states more flexibility to respond to the sudden changes brought by COVID-19 and ensure that consumers had adequate access to care.24Ethan Bayne, Conor Norris, and Edward J. Timmons, “A Primer on Emergency Occupational Licensing Reforms for Combating COVID-19,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, March 26, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/covid-19-policy-brief-series/primer-emergency-occupational-licensing-reforms-combating. While the changes were intended to help patients during a surge in demand, they should lead policymakers to consider who the laws protect under normal conditions: the public or professionals. We focus on three main categories of waivers:

- Expanded scope of practice for nurse practitioners, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and physician assistants: Some states have waived the requirement of physician supervision of professions such as physician assistants (PA), nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNA). Ohio and Tennessee have extended the authority to write prescriptions for select controlled substances to CRNAs and PAs, Vermont and Wisconsin have expanded the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and PAs.

- Universal recognition of medical personnel: Many states have allowed license holders from other states to get an emergency license to This allows health care professionals to move into states to quickly respond to a spike in demand, thereby better allocating human capital based on changes in needs across states.

- Alternate pathways: States have temporarily waived or reduced licensing requirements in order to quickly expand the number of professionals. Such policies allow students waiting to take licensing exams to practice under the supervision of another licensed professional, thereby augmenting health care

Framework for Occupational Licensing Reform

If policymakers in Washington, DC, want to encourage a rapid economic recovery and enact reforms to improve future pandemic responses, occupational licensing reform is a promising starting point. State policymakers should consider reforming licensing laws to get more of their citizens back to work and to make their economies more resilient to future challenges.

The disruption caused by COVID-19 is likely to have long-lasting effects by changing people’s needs and behaviors. The successful industries going forward will likely be different; for instance, there may be a greater focus on health care, less traveling, and fewer activities involving large groups. It is difficult to know exactly in what ways or how much behavior will change, so our policies should encourage flexibility and worker reallocation as new industries emerge and replace old industries. The shelter-in-place orders caused significant strain for small businesses, resulting in many business failures. Barriers to entry that reduce entrepreneurship, such as occupational licensing,25Silvia Ardagna and Annamaria Lusardi, “Explaining International Differences in Entrepreneurship: The Role of Individual Characteristics and Regulatory Constraints,” NBER Working Paper No. 14012, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2008, https://www.nber.org/papers/w14012.pdf. should be reduced to encourage new business formation after the failure of so many businesses to help spur the recovery.

Additionally, reforming licensing for health care professions would help our health care system as a whole become more resilient in the face of future pandemics or a second wave of COVID-19 infections in the fall. Given the speed at which states waived requirements during the initial outbreak, there is an emerging view that these requirements were not only unnecessary but actively harmful to patients, making it more difficult for them to receive care. Most of the temporary measures were tied to governors’ declarations of a state of emergency, so they will expire if the state of emergency ends. Instead of resuming licensing requirements, states should be encouraged to make these temporary measures permanent.

The best starting point for federal and state policymakers is requiring that states reconsider the professions that they license and the steps for getting those licenses. Typically, once an occupation is licensed in a state, the state’s legislature does not conduct a retrospective analysis.

We outline five potential reforms below: creating Fresh Start Initiatives, instituting universal recognition, reducing barriers to entry, offering a path to licensure through experience, and creating stronger sunrise- and sunset-review processes for licensure.

Fresh Start Initiatives

Fresh Start Initiatives are modeled on the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission’s process for determining which military bases to close in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War. Implementing such initiatives at the state level could remove the barriers that lock workers out of licensed professions.26Patrick McLaughlin, Matthew Mitchell, and Adam Thierer, “A Fresh Start: How to Address Regulations Suspended during the Coronavirus Crisis,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, March 26, 2020, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/mclaughlin-fresh-start-coronavirus-mercatus-v1.pdf.

As the Cold War ended, the United States had more military bases than necessary. Once a military base exists, it is difficult to close because it creates vested interests in its continued existence.27Jerry Brito, “Running for Cover: The BRAC Commission as a Model for Federal Spending Reform,” Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Policy 9, no. 131 (2010), https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Brito-BRAC.pdf. Groups lobby to maintain a base as a way to provide economic benefits to a town or state rather than defense for the United States as a whole. Any representative supporting the closure of a base in her district would lose her seat, with local supporters of the base vehemently opposing reelection. With the normal political process, no bases would be closed. Despite the widespread agreement that too many bases were in operation, each interest group would oppose the closure of its own local base.

To avoid this issue, the BRAC Commission experts determined which bases to close, based on their military value and cost of operation. In voting for the creation of the BRAC Commission, Congress agreed to abide by the decisions of the commission. As one economist summarizes,28Matthew D. Mitchell, “Overcoming the Special Interests That Have Ruined Our Tax Code,” in Adam J. Hoffer and Todd Nesbit, eds., For Your Own Good: Taxes, Paternalism, and Fiscal Discrimination in the Twenty-First Century (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3173846. an individual vote for BRAC is a “conspicuous vote in favor of cutting unnecessary military spending. But the commission itself decides which particular bases to close, allowing the member whose hometown base is closed to tell constituents that her hands were tied.” The commission’s decision could only be undone through a joint resolution of Congress. Each representative of a district with a closing base could call for a vote on a joint resolution and give an impassioned plea for his district’s base, allowing him to save face with voters while leaving little chance of the decision being overturned. This process aligned the individual legislator’s interest in reelection with the ordinary consumer’s interest in a thorough and binding review.

Approaches like the BRAC Commission have been proposed to make difficult reforms in other policy areas more palatable, such as tax policy.29Mitchell, “Overcoming.” Based on the lessons from the BRAC Commission, regulatory economists developed Fresh Start Initiatives as a way to shrink the growth of rules such as licensing rules to useful levels. Even though licensing has extensive economic costs for the entire economy, licensed individuals are better off because of them. That incentivizes them to lobby for licensure’s continuation. Fresh Start Initiatives would create state-level commissions whose role is to study the rules that states revised or suspended in response to COVID-19. The commissions would recommend reforms based on those temporary measures and create a timetable for the reform or sunset of the licensing regulations being considered.

Implementing a Fresh Start Initiative would require state officials to bind themselves to the commission’s recommendations for reducing red tape. This could be done in two ways. First, recommendations could become effective when issued by the commission. Second, the recommendations could become binding by requiring that a state legislature vote on the reforms in all-or-none form. The commission would estimate the costs imposed by occupational licensing, including the increase in prices, the reduction in access to professionals, and the lost opportunity of those prevented from entering the field, along with the benefits of increases in quality and consumer protection. The commission would weigh these costs and benefits and make recommendations. If the whole package of reforms passed, then the commission would dissolve or hibernate for a defined amount of time, perhaps three years, before reconvening to reevaluate the changes. If the package failed, then the commission would issue another set of recommendations to the state legislature. As with the BRAC Commission, only a supermajority could vote to override the Fresh Start Initiative’s ruling. This would prevent special interests from influencing legislators to spare their profession from reform.

As an illustration of how a Fresh Start Initiative might work, consider cosmetology licenses. The case for licensing cosmetology is that dirty hair clippers and the use of dyes and other chemicals present public health risks. A Fresh Start Initiative would create a commission that would compare these risks with the costs associated with occupational licensing. The commission could then recommend an appropriate response in lieu of licensing professionals, such as instituting periodic health inspections like those that restaurants undergo or requiring cosmetologists to pass a test about on-the-job safety to attain something equivalent to a food handler’s permit.

Universal Recognition

Universal-recognition laws require that state licensing boards grant licenses to professionals already licensed in another state. They can help power an economic recovery by allowing workers to more easily move to areas where their skills are needed.30Stephen Slivinski, “You Can Take It with You: A Case for Occupational Licensing Reciprocity,” Center for the Study of Economic Liberty at Arizona State University, March 2, 2020, https://csel.asu.edu/sites/default/files/2020–02/CSEL-2020–01-You-Can-Take-It-with-You-03_02_20.pdf.

In 2019 Arizona became the first state to pass a universal-recognition law.31Arizona Governor’s Office, “Arizona First in the Nation: Universal Licensing Recognition,” 2019, https://azgovernor.gov/sites/default/files/universallicensingrecognition1_0.pdf?TB_iframe=true&width=921.6&height=921.6. Any licensed professional who has practiced in another state without disciplinary action can practice in Arizona after moving to the state. In the first year alone, over 750 professionals moved to Arizona to take advantage of the reciprocity.32Mark Flatten, “Hundreds of Arizonans Already Benefiting from Breaking Down Barriers to Work,” In Defense of Liberty, February 24, 2020, https://indefenseofliberty.blog/2020/02/24/hundreds-of-arizonans-already-benefiting-from-breaking-down-barriers-to-work/. Iowa and Missouri passed similar legislation this year.33Heather Curry, “Missouri Should Act Now to Break Down Barriers to Work,” In Defense of Liberty, April 29, 2020, https://indefenseofliberty.blog/2020/04/29/show-me-state-should-show-support-for-breaking-down-barriers-to-work/.

In order for a universal-reciprocity law to be effective, it must be designed properly. Idaho, Pennsylvania, Montana, and Utah have passed weaker versions of universal reciprocity than Arizona’s version.34Edward Timmons, “Edward Timmons: New Law Makes It Easier to Work in Pennsylvania,” TribLIVE.com, August 3, 2019, https://triblive.com/opinion/edward-timmons-new-law-makes-it-easier-to-work-in-pennsylvania/. While they provide more reciprocity than other states, they still give boards power to deny licenses to professionals moving to the state if the boards deem that the professionals’ previous state’s requirements were not substantively equivalent.

The consumer-protection argument for licensing relies on the fact that doctors know more than their patients. This information asymmetry makes it possible for some practitioners to take advantage of their customers—for example, by overcharging them for simple procedures. So licensing laws were created to protect consumers from charlatans.35 Hayne E. Leland, “Quacks, Lemons, and Licensing: A Theory of Minimum Quality Standards,” Journal of Political Economy 87, no. 6 (1979): 1328–46. Today, consumers can read reviews of licensed workers before seeking out their services. Economists and regulation scholars have pointed out that the internet and the sharing economy resolve much of the information asymmetry.36Adam Thierer, Christopher Koopman, Anne Hobson, and Chris Kuiper, “How the Internet, the Sharing Economy, and Reputational Feedback Mechanisms Solve the Lemons Problem,” University of Miami Law Review 70, no. 3 (May 1, 2016): 830–78. One recent paper suggests that consumers may even prefer this online-review information to simply information about licensure status.37 Farronato et al., “Consumer Protection.” This literature provides more evidence in favor of peeling back many licensing regulations.

COVID-19 is likely to cause permanent changes to our economy, so removing barriers to interstate migration is important to ensure that industries are able to expand to meet consumer needs wherever they arise. Universal recognition reduces the barriers to migration, but it only helps professionals who have already obtained a license. Those blocked from entry are still not able to begin working in the licensed field.

State-to-State Comparisons

States with particularly high licensing requirements should reduce them to the national average or to the lowest quartile—for example, by reducing fees and training days required.

The Institute for Justice shows that licensing requirements vary substantially across states even for the same occupation. In Alabama, a cosmetologist pays $235 in licensing fees and engages in 1,500 hours of training. In neighboring Florida, those figures are only $90 and 1,200 hours.38Dick Carpenter, Lisa Knepper, Kyle Sweetland, and Jennifer McDonald, License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, 2017), https://ij.org/wp-content/themes/ijorg/images/ltw2/License_to_Work_2nd_Edition.pdf. That means Alabama’s fees are 160 percent higher than those in Florida. The 300-hour difference means that it takes seven and a half extra work weeks to obtain a license in Alabama.

Many other occupations’ requirements diverge widely. Auctioneers in Minnesota are required to pay $20, and they face no training requirements, but auctioneers in Tennessee must pay $750 and undergo 110 hours of training. An aspiring optician in New Hampshire must pay a $110 fee and does not have to undergo any specific training or educational program before practicing. However, that same individual would have to pay a $943 fee and undergo 731 days of training if she lived in Florida. A massage therapist in New Jersey is required to pay $176 and undergo 500 hours of training, while just across the border in New York a massage therapist must pay $368 and undergo 1,000 hours of training.39Carpenter et al., License.

Research shows that those differences have little or no effect on the quality of services. But the more onerous requirements do represent a greater barrier to entry. One paper finds that increases in licensing fees is associated with licensed businesses hiring fewer employees. The same study finds that increases in the number of days of training a state requires to obtain a license is associated with businesses being more likely to open in a nearby state with lower requirements.40Alicia Plemmons, “Occupational Licensing Effects on Firm Entry and Employment,” Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, June 26, 2019, https://www.thecgo.org/research/occupational-licensing-effects-on-firm-entry-and-employment/. States can maintain the quality of services and make it easier for aspiring professionals to enter an occupation by reducing licensing requirements to align with the national average.

Beyond the differing licensing requirements, many states license occupations that others do not.41Carpenter et al., License. Residential HVAC contractors are not licensed in fifteen states, and drywall installation contractors are not licensed in twenty-one states. Interior designers are only licensed in two states and Washington, DC. Louisiana is the sole state that licenses flower arrangers, and it persists despite evidence that the licensing does not improve the quality of flower arrangements.42Dick M. Carpenter II, Blooming Nonsense (Institute for Justice, March 2010), https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/laflowerreportfinalsm.pdf.

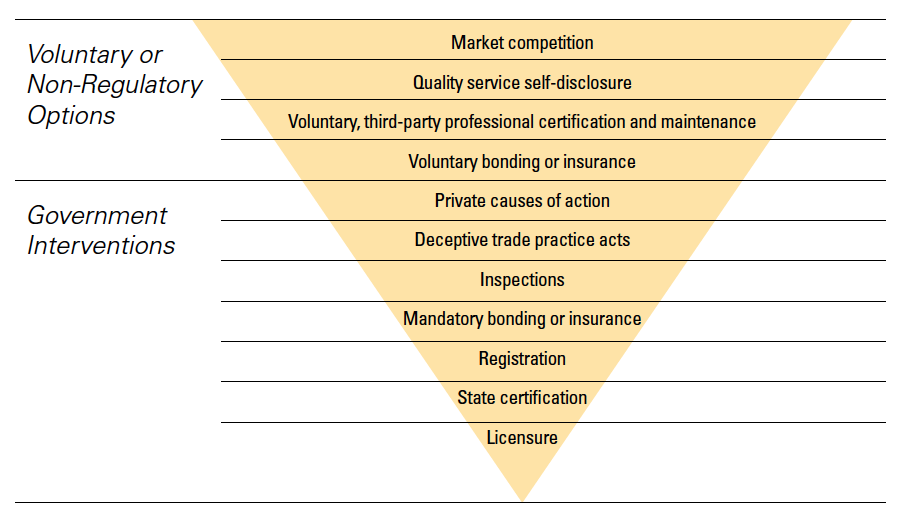

For occupations that are not licensed in more than 50 percent of states, state policymakers should give serious consideration to eliminating licenses in favor of pursuing alternative policies. The federal government could require that licensing boards or legislatures explain why licensing is the appropriate policy tool to serve the public interest. Licensing laws are the most stringent form of labor-market regulation. Some of the less stringent alternatives, such as certification, titling, registration, or mandatory bonding and insurance, may be more appropriate for the risks involved in certain professions.43John K. Ross, The Inverted Pyramid: 10 Less Restrictive Alternatives to Occupational Licensing (Institute for Justice, November 2017), https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Inverted-Pyramid_FINAL_cover.pdf. Milton Friedman suggested many of the same reforms. See chapter 9 of Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: Fortieth Anniversary Edition (University of Chicago Press, 2009). In the figure below, we show the regulatory options to protect consumers, from least restrictive to most restrictive.

Figure 2: The inverted pyramid: alternatives to licensing4444 Ross, Inverted Pyramid.

Under a certification regime, professionals can obtain a credential to signal their quality, but the certification is not required for them to practice. This allows individuals to enter a field without having to attain a set amount of education, while still providing consumers with information about the quality of the professionals.

Title protection restricts use of a title to professionals that meet a state’s requirements, but anyone can offer services without the use of the title. For instance, under title protection, anyone can offer personal-trainer services, but only a professional who has met the state’s requirements may refer to herself as a certified personal trainer.

Under registration, the government does not require any education or training but does require that professionals submit their name and contact information to the state as a condition for offering their services. This provides protection for consumers by making it easy for them to bring civil actions against professionals.

Finally, states can require that professionals get a surety bond or insurance to protect customers and third parties from risks.

State licenses grant a monopoly and should therefore be subject to detailed evaluations. If state policymakers and licensing boards cannot provide evidence that the cost of licensing a profession is justified by protecting public safety, the profession should not be subject to licensure. It is unlikely that a professional licensed in a handful of states is protecting public health when unlicensed professionals are not considered a threat in other states.

Offering Licensing through Experience

States can expand the number of pathways to licensure by allowing individuals to use relevant experience to prove competency and obtain a license. Historically, apprenticeships were the path into a field. For example, before law schools became common, apprenticeship and mentorship was the path to working as a lawyer. California and six other states still maintain a form of this path.45Debra Cassens Weiss, “Students Try to Avoid Law School Costs with ‘Reading Law’ Path to Law License,” American Bar Association Journal, July 30, 2014, https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/want_to_avoid_the_costs_of_law_school_these_students_try_reading_law_path_t.

Another example of using relevant experience and training for obtaining a license is the Military Medics and Corpsmen (MMAC) Program in Virginia. MMAC allows military veterans to use their military experience by entering the civilian medical field and practicing at a level in line with their experience while earning credentials.46“Military Medics and Corpsman Program Applicant Action Guide,” Virginia Department of Veteran Services, July 1, 2016, https://www.dvs.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MMAC-APPLICANT-ACTION-GUIDE-4–19.pdf.

A bill proposed in Washington State would have provided more pathways to licensing via experience, but the bill died in committee.47“HB 2355 – 2019–20 Creating Alternative Professional Licensing Standards,” May 4, 2020, https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=2355&Year=2019&Initiative=false.

Sunrise and Sunset Reviews

Some states, such as Colorado and Texas, conduct sunrise and sunset reviews before licensing occupations or moving forward with liberalization of licensure. Sunrise reviews consider occupations for which licensing is being proposed. Under a sunset review, each licensing or regulatory board is set to expire. A sunset commission compares the benefits of consumer-protection laws such as certification requirements and licensing regulations to their economic costs and impact on applicants. It then makes recommendations to the legislature. It can recommend reforming the board or abolishing it. Legislators are then required to vote on whether to continue the board’s existence.

Like Fresh Start Initiatives, sunrise and sunset reviews compare the costs and benefits of licensure. Unlike Fresh Start Initiatives, they are regular and repeated analyses. A prospective analysis is performed before the regulation is decided upon, and retrospective analyses are periodically performed after the regulation has been implemented. Fresh Start Initiatives focus on the buildup of licensing laws since 1950. Sunrise and sunset reviews are more focused on regulatory housekeeping.

There are strong reasons to be skeptical of the effectiveness of sunrise and sunset reviews. Regulatory-agency evaluations are not legally binding, and legislatures can ignore the recommendations of the agency’s expert staff. The clearest example comes from Colorado’s sunrise review of licensure of genetic counselors. In three separate reviews, DORA, the regulatory agency that conducts sunrise reviews in Colorado, recommended against licensing genetic counselors.48“2004 Genetic Counselors Sunrise Review,” Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies Office Policy, Research and Regulatory Reform, October 15, 2004, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dlVbtG_rVUvRYvXd3y2t0Dchzo1-_897/view?usp=embed_facebook; “2013 Sunrise Review Genetic Counselors,” Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies Office Policy, Research and Regulatory Reform, October 15, 2013, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KN6xS_ISJF9F iuDgGXe4Ta3yO–aam/view?usp=embed_facebook; “2017 Sunrise Review Genetic Counselors,” Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies Office Policy, Research and Regulatory Reform, October 13, 2017, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B1eD7wvZltwxS2IyWlRKYzZkelE/view?usp=embed_facebook. The first time DORA considered and rejected licensing genetic counselors was in 2004, with two subsequent reports in 2013 and 2017 reaching the same conclusion that licensing was not necessary.49“2004 Genetic Counselors Sunrise Review”; “2013 Sunrise Review Genetic Counselors”; “2017 Sunrise Review Genetic Counselors.” In 2019 the legislature ignored those three reports and passed a law to create a genetic-counseling license. On May 31, 2019, Governor Polis vetoed the law, along with two other licensing proposals.50Vincent Carroll, “Carroll: Polis’ Three Good Vetoes Are a Warning to Lawmakers about Government Restraint,” Denver Post, June 9, 2019, https://www.denverpost.com/2019/06/09/carroll-polis-three-vetoes-government-restraint/. In his veto letter, Polis pointed to the reviews by DORA as justification and called for broader thinking than sole reliance on licensing for consumer protection: “Occupational licensing is not always superior to other forms of consumer protection. Too often it is used to protect existing professionals within an occupation against competition from newcomers entering that occupation.”51Jared Polis, “Veto Statement Senate Bill 19–133,” Colorado Governor’s Office, May 31, 2019, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7w3bkFgg92dSVZtbE1KdnBxbndPSWhtNHd5ZWd3ME93TkNZ/view?usp=embed_facebook.

Colorado’s experience with genetic counseling is reflected in research on reversing licensing via sunrise reviews. A study in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Monthly Labor Review summarizes the rare cases in which occupations were successfully liberalized. Its conclusion echoes Polis’s veto letter: “The paucity of successful de-licensing efforts is due to intense lobbying by associations of licensed professionals as well as the high costs of sunset reviews by state agencies charged with the periodic review of licensing and its possible termination.”52Robert J. Thornton and Edward J. Timmons, “The De-Licensing of Occupations in the United States : Monthly Labor Review: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,” Monthly Labor Review, May 18, 2015, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/the-de-licensing-of-occupations-in-the-united-states.htm.

Given this research and Colorado’s experience, it is important to ensure that the recommendations made by sunrise and sunset reviews be taken seriously by legislators. Considerable evidence suggests that licensing’s recent growth has been caused by licensed professionals’ intense lobbying of policymakers. When legislatures are able to easily override or ignore a sunset commission’s recommendations, the recommendations have little effect on licensing.

The benefits of sunrise and sunset reviews may stem more from informing nonlegislative officials, as in the case of the three gubernatorial vetoes in Colorado. Ohio and Nebraska have enacted sunset reviews that are coupled with guidance to the legislature to use the least restrictive form of regulation when feasible.53Nick Sibilla, “New Ohio Law Takes Aim at Occupational Licenses, Which Cost State $6 Billion,” Forbes, January 9, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nicksibilla/2019/01/09/new-ohio-law-takes-aim-at-occupational-licenses-which-cost-state-6-billion/; Eric Boehm, “Nebraska Just Passed a Major Occupational Licensing Reform Measure. Here’s Why It Matters,” Reason.com, April 18, 2018, https://reason.com/2018/04/18/nebraska-just-passed-a-major-licensing-r/. Time will tell how effective these reforms will be and whether reviews can be shielded from regulatory capture.

Conclusion: A Fresh Start for All

Fresh Start Initiatives, universal recognition, and expanded scope of practice represent opportunities for state-level initiatives to reduce the burdens of occupational licensing. The temporary waivers of regulations in response to COVID-19 give regulators reason to reconsider whether current regulations effectively protect consumers. These proposed measures would unlock human potential that is stymied by licensing laws. They would promote a fast return to economic prosperity in the wake of COVID-19.

Awareness of the economic costs of licensing motivated reforms well before COVID-19 became a national concern. In light of the pandemic, licensing reform has only become more important.

Thoughtful action now can lay the groundwork for a more robust economic future. State-level revisions of licensing laws would be an important step toward a lasting economic recovery in which job opportunities for millions of American workers are expanded