In the early 1990s, Vintondale, PA was like many other former mining towns. It was quiet, sparsely populated…and its river stained orange by the acidic water leaching from abandoned mines in the area.

This sight was commonplace across Pennsylvania for decades, a state with an extensive mining history. Yet today, the river flowing through Vintondale looks very different. It is one of the many projects completed under the Pennsylvania Environmental Good Samaritan Act.

This act allows private parties to clean up abandoned mines without having to worry about being sued for not doing a perfect job. Now the area has been transformed into a park that filters the water through a passive water treatment system, contains artwork that celebrates the mining heritage of the area, and provides recreational opportunities for the local residents.

Although the toxic site in Vintondale has been addressed, abandoned mines, empty warehouses, and vacant factories can be found across the entire United States. Hundreds of thousands of these sites contain hazardous materials that threaten the health and well-being of nearby communities. And while certain hazardous sites have received much attention over the past few decades, overall progress to clean them up has been painstakingly slow.

Part of the problem is that current legislation discourages voluntary efforts by forcing would-be-do-gooders to assume liability for the sites they are attempting to clean up. This all-or-nothing approach to hazard remediation has made perfection the enemy of progress.

Re-thinking the liability laws applied to many of these sites can make it easier for third-party groups to participate in preservation projects without punishing them for wanting to improve their community. Currently, Pennsylvania is the only state that has passed significant environmental Good Samaritan legislation. But that may soon change.

Earlier this year, Senators from Idaho and New Mexico introduced the Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act, which would make Good Samaritan protections available across the country. This bill could serve as a major step towards cleaning hazardous sites that have harmed so many American communities for far too long.

Background of Superfund Sites

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) oversees all major hazardous waste clean-up projects as established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). Under CERCLA, the Superfund program was established. In the program, the most toxic areas in the United States are categorized as Superfund sites. The EPA then focuses its resources to clean up those sites. These areas include old mines, abandoned chemical plants, municipal landfills, and deserted army bases. And it may surprise you how common these sites are.

Since the signing of CERCLA in 1981, the EPA has designated 1769 areas as Superfund sites. Nearly one out of every four Americans live within 3 miles of a Superfund site. Although the effects can vary depending on the toxicity of the site, Superfund sites have been linked to severe health problems such as increased cancer rates and a higher incidence of birth defects in children.

Despite the many efforts that have been made to improve these polluted areas in recent years, remarkably few of them have been completely cleaned up. The Trump Administration made substantial efforts to clean up hazardous sites within the Superfund program. The 46 sites remediated between 2017 and 2020 are the most in a single presidential term since the Clinton Administration when they cleaned up 181 sites.

It appears the Biden administration is also making strides to bolster the Superfund program. The infrastructure bill passed in November 2021 put $21 billion towards Superfund and other environmental remediation projects. Yet, pouring money into these projects has failed to make significant improvements and ignores other critical problems, such as litigation, that have hindered progress up until now.

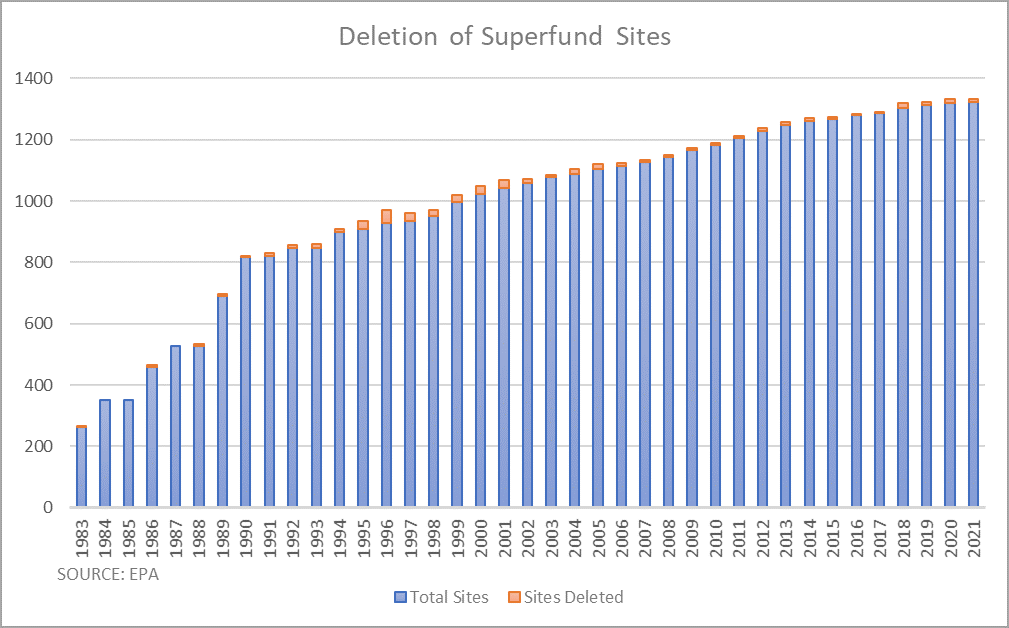

As you can see in the graph below, the number of new sites listed each year continues to outpace the number of sites being cleaned up. And this graph only includes Superfund sites, the most toxic areas in the US. There are an estimated 450,000 additional properties across the US that are believed to contain hazardous materials.

Currently, almost all cleanups are managed by either government agencies or the organizations responsible for the pollution. But it is clear that if we want to have any hope of really getting on top of the hazardous waste issue in the US, we have got to change the way we are currently operating. And one of the best ways to do that is to make it easier for third-party groups to get involved.

The Cleanup of Abandoned Mines

Voluntary efforts to clean up abandoned mines (and the barriers that often stand in the way of doing so) provide a great example of the issues present in the current system.

Dealing with polluted water that comes from mines is a complicated issue since it is governed by the Clean Water Act. Groups that want to treat contaminated water from mines must get a discharge permit from the EPA. That permit requires that the project meet high standards of water quality. In a congressional hearing on abandoned mines, an EPA official commented,

“Under the CWA, a party may be obligated to obtain a discharge permit which requires compliance with water quality standards in streams that are already in violation of these standards… Yet, in many cases, the impacted water bodies may never fully meet water quality standards, regardless of how much cleanup or remediation is done. By holding Good Samaritans accountable to the same cleanup standards as polluters or requiring strict compliance with the highest water quality standards, we have created a strong disincentive to voluntary cleanups. Unfortunately, this has resulted in the perfect being the enemy of the good.”

The court case that set the precedent for this issue came from a lawsuit brought by the Committee to Save Mokelumne River against the East Bay Municipal Utility District and members of the California Regional Water Quality Control Board. East Bay had noticed that an abandoned mine was leaking heavy metals into the water supply. So they built a series of ditches, along with a small dam and reservoir, to limit the amount of pollution that escaped. This allowed them to regulate the toxins flowing from the mine and resulted in a “significant improvement in the river’s environment and a boon to aquatic life.”

However, with heavy rain, the reservoir would overflow and leak some of the pollutants into the Mokelumne River. Even though the changes had created a net improvement in the quality of the river, East Bay was sued by a local environmental group under the Clean Water Act (CWA). The court ruled that under the CWA, the utility district was now responsible for the mine runoff because they had

“(1) discharged a pollutant (i.e., collected and channeled surface runoff containing acid mine drainage into the reservoir and then added the polluted runoff); (2) into navigable waters (i.e., the Mokelumne); (3) from a point source (i.e., the dam’s spillway and valve); (4) without a discharge permit”

and would be forced to undertake a costly cleanup of the area. One of the judges ruling on the case worried about the negative consequences that could arise from the decision. In his concurring opinion, he wrote,

“[I]t takes no genius…to see what the message will be. Do nothing! Let someone else take on the responsibility. Let the water degrade, let the fish die, but protect your pocketbook from vast and unnecessary expenditures.”

It didn’t take long for the news of the ruling to get out. Shortly following the ruling, the executive director of the California State Water Resources Control Board sent out a memorandum to all the regional boards that effectively said,

“Do nothing. Don’t embark on any mine waste cleanup problems because the State can end up holding the bag.”

Many volunteer groups do not have the resources necessary to pass the lofty water quality standards set by the CWA. However, there are ways that these groups can improve the status quo. For example, passive water treatment systems, such as the one used in Vintondale, PA, are a cost-effective method for treating polluted water from abandoned mines. Digging trenches around mines to prevent rain runoff from becoming contaminated is another simple way to reduce pollution. Lowering these water quality standards would allow third parties to improve the condition of contaminated sites in meaningful ways without placing them under threat of potential litigation.

Taking Action

Oddly enough, environmental groups are still among the most vocal opponents to limiting liability for non-responsible parties. The organizations EarthWorks and Earthjustice both fear that such laws would provide costly exemptions from major environmental protection laws. They worry that this would allow organizations or companies to use the exemptions as loopholes to continue degrading the environment.

Yet, since Pennsylvania passed the Good Samaritan Act in 1999, the state has seen the condition of its streams and waterways improve. In the first twenty years of the program, over 80 different projects were completed, involving 44 different groups and individuals.

The West Branch Susquehanna, a 242-mile stretch of the Susquehanna River, had been hit hard by pollution. In 1972, the pH level of the river was so acidic that it was uninhabitable for almost all fish. But thanks to voluntary efforts, by 2009, the pH level in the river had returned to healthy levels and fish species in the river had increased by 3,000 percent.

Pennsylvania has also expanded the Good Samaritan program to include the cleanup of abandoned oil and gas wells. Put simply, the program has been a resounding success.

Other states have noticed the success of Pennsylvania’s Good Samaritan Program. U.S. Senators Jim Risch (R-Idaho) and Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) are promoting the cleanup of hazardous sites through the bipartisan Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act. It is similar to the Pennsylvania law in that it limits third-party liability, but different in that it would launch a Good Samaritan pilot program.

Under this program, only a maximum of 15 projects could be approved. This is an important step on the way to convincing naysayers of the advantages of such a program. Past attempts at passing environmental Good Samaritan legislation have failed due to opposition from environmental groups.

Cleaning up hazardous sites both betters the environment and improves the health of those living nearby. There is surely no such thing as “too soon” to clean up hazardous sites and the threat of litigation caused by unnecessarily strict environmental regulations has hindered remediation efforts for too long.

When it comes to addressing pollution, we can’t allow the lofty pursuit of environmental perfection to get in the way of real environmental progress.