Introduction

More than a century after its enactment, the Antiquities Act, which authorizes the president to declare national monuments on federal lands, continues to generate controversy. Almost from the beginning, opponents of monument designations have criticized the Antiquities Act’s reach, vague standards, and broad executive powers. More recently, national-monument supporters have challenged President Donald Trump’s decision to downsize Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Bears Ears National Monument substantially, denying that the president has such power. They argue that the Antiquities Act authorizes the president only to “declare” national monuments and therefore implicitly omits the power to alter monuments once declared. At heart, the two sides of the debate share a common foundation: concern about unconstrained presidential power.

On two past occasions when the Antiquities Act generated substantial controversy, Congress responded with legislation imposing modest limits on presidential power. Yet the effect of those changes is not well known. This paper analyzes them to see what lessons can be drawn for the current controversies and any potential congressional response.

In 1950 and 1980, Congress responded to the president’s contentious use of the Antiquities Act by limiting its application in Wyoming and Alaska, respectively. Subsequent experiences in those states suggest three significant lessons for future Antiquities Act reforms. First, limiting the president’s power can encourage Congress to take renewed interest in federal land management, as shown by Congress’s more active exercise of its wilderness-designation authority in Wyoming and Alaska. Second, threshold limits on presidential action effectively can deter controversial actions without interfering with the president’s power to protect discrete objects by designating smaller monuments or making modest boundary adjustments. Alaska has had a five-thousand-acre limit on federal land withdrawals for nearly forty years, and no president has attempted to circumvent it. Finally, other federal laws enacted in the latter half of the twentieth century offer additional protections to valuable resources on federal lands, making them less dependent on the Antiquities Act.

Although proponents and opponents of the act disagree about what actions are troubling, both sides’ ultimate concern is the president’s assertion of broad, unreviewable power. Thus, depending on how several ongoing lawsuits are resolved, opportunities for compromise may now exist, such as hedging in presidential power from both sides. In any event, to the extent that Congress considers responding to either aspect of the current controversy, past efforts provide useful evidence of how different potential reforms might work in practice.

The Antiquities Act

Enacted to protect Native American sites in the Southwest from immediate threats such as looting, the Antiquities Act authorized the president quickly and unilaterally to protect “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated on land owned or controlled by the Federal Government.”1 54 U.S.C. § 320301(a). See James McElfish et al., Antiquities Act: Legal Implications for Executive and Congressional Action, 48 Envtl. L. Rev. 10,187, 10,197 (2018) (remarks by Mark Squillace arguing that the basic policy behind the Antiquities Act is to allow the president to act quickly to prevent immediate threats). That power is exercised by issuing a presidential proclamation announcing the landmarks, structures, or objects as national monuments, without any requirement for the public to comment or the president to create a record to support the proclamation’s determinations.254 U.S.C. § 320301(a). See Mark Squillace, The Monumental Legacy of the Antiquities Act of 1906, 37 Georgia L. Rev. 473, 570–81 (2003) (noting the role of the Antiquities Act’s lack of public process in its simmering controversy).

Once a monument is declared, the president may “reserve parcels of land” for the objects’ protection, withdrawing them from eligibility for a variety of land uses, such as mining or grazing.354 U.S.C. § 320301(b). See generally Justin James Quigley, Grand-Staircase Escalante National Monument: Preservation or Politics?, 19 J. of Land, Res., & Envtl. L. 55 (1999) (discussing uses of the Antiquities Act to block anticipated mining development). Such declarations are limited, in the law’s language, to “the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected,” which has been interpreted to impose only loose limits on the president’s discretion.454 U.S.C. § 320301(b). See Mountain States Legal Found. v. Bush, 306 F.3d 1132, 1134–38 (DC Cir. 2002) (holding that national-monument designations are judicially reviewable but that such review is highly deferential to the president).

Monument proclamations routinely include regulations on future use of the lands within the monument’s boundaries.5See, e.g., Presidential Proc. Establishing Hanford Reach National Monument (June 9, 2000), available at https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/CEQ/hanford_reach_proclamation.html (prohibiting livestock grazing and off-road travel on all federal lands within the monument). The Antiquities Act provides further that the secretaries of the interior, agriculture, and the army shall promulgate “uniform rules and regulations” to carry out the Antiquities Act’s purpose, which has been interpreted to authorize administrative management plans for monument lands.6 54 U.S.C. § 320303. See, e.g.,Giant Sequoia National Monument Management Plan (Sept. 4, 2012), available at https://www.fs.fed.us/r5/sequoia/gsnm_planning.html.

Thus the Antiquities Act grants the president significant discretion in designating and managing national monuments. It does so by allowing the president to designate national monuments “in his discretion” but not requiring a designation in any circumstances.754 U.S.C. § 320301(a). See McElfish et al., supra n. 1, at 10,193. And although the Antiquities Act limits the president’s authority, those limits are sufficiently ambiguous as to confer significant discretion.8See Jordan K. Lofthouse and Megan E. Hansen, Executive Discretion and the Antiquities Act, Center for Growth and Opportunity Policy Paper 2019.002 (May 2019), available at https://www.growthopportunity.org/archives/2019/policy-paper-2019.002.pdf. One indication of just how weak are the limits on the president’s power is that in the 113 years since the Antiquities Act was passed, no court has struck down a monument designation for exceeding those limits.9See Utah Ass’n of Counties v. Bush, 316 F.Supp.2d 1172, 1179–80 (D. Utah 2004) (collecting cases). The absence of judicial action does not imply that courts never would strike down a monument designation for exceeding the law’s limits. The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit has indicated that it would do so, but it has yet to be presented with a proper case. See Mountain States, 306 F.3d at 1138.

Similarly, the Antiquities Act has long been interpreted to grant the president broad discretion to alter existing national monuments. Seven presidents have used that power to reduce the size of national monuments, in some cases substantially.10 See John Hudak, President Trump Has the Power to Shrink National Monuments, Brookings Inst. (Dec. 7, 2017), available at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2017/12/07/president-trump-has-the-power-to-shrink-national-monuments/. Presidents have cited a wide variety of public purposes for those reductions, suggesting that the same open-ended discretion that applies to monument designations also applies to reductions. 11See John Yoo and Todd Gaziano, Presidential Authority to Revoke or Reduce National Monument Designations, 35 Yale J. on Reg. 617, 662–63 (2018) (describing the president’s justifications for several past significant reductions). But no president has revoked an existing monument designation, likely because a 1938 opinion of the attorney general disputes the claim that the president has such power.1239 Op. Att’y Gen. 185, 185 (1938). The question of whether the president has the power to modify or revoke existing national monuments remains unresolved today. 13See Yoo and Gaziano, supra n.11 (disputing the conclusion of the attorney general’s opinion); Squillace et al., Presidents Lack the Authority to Abolish or Diminish National Monuments,103 Va. L. Rev. Online 55 (2017). Although a full discussion of the issue is beyond the scope of the present paper, the author’s view is that the president may modify or revoke national monuments at will. See McElfish et al., supra n.1.

Controversy and Reform

Because the Antiquities Act grants the president broad, unilateral power, its exercise has generated periods of controversy, followed by legislative responses and then periods of presidential restraint.14See Yoo and Gaziano, supra n.11. Historically, most of the controversy has focused on the large size of monuments.15 See, e.g., Nicolas Loris, The Antiquated Act: Time to Repeal the Antiquities Act, Heritage Found. Rep. (2015), available at https://www.heritage.org/environment/report/the-antiquated-act-time-repeal-the-antiquities-act. But almost all of the law’s ambiguities have led to some degree of conflict. For example, the president has been criticized for interpreting the “objects” covered by the Antiquities Act expansively to include vast ecosystems and scenic vistas,16Memo from Sec. of the Interior Ryan Zinke to the president, Final Report Summarizing Findings of the Review of Designations under the Antiquities Act 2, 6–7 (2018), available at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4052225-Interior-Secretary-Ryan-Zinke-s-Report-to-the.html. for interpreting “land owned or controlled by the federal government” to include the ocean and ocean floor beyond the nation’s territorial sea (the first twelve miles of ocean beyond the coast, over which a nation’s sovereignty extends), 17The author represents commercial fishermen in a case challenging a five-thousand-square-mile monument in the Atlantic Ocean more than one hundred miles from the nation’s coast, arguing that the ocean and ocean floor beyond the territorial sea are not “land owned or controlled by the federal government.” Mass. Lobstermen’s Assoc. v. Ross, 349 F.Supp.3d 48 (D.D.C. 2018), appeal pending No. 18–5353 (D.C. Cir. filed Dec. 3, 2018). The district court upheld the monument, relying on an Office of Legal Counsel memo concluding that federal authority over the exclusive economic zone is sufficient to constitute “control” under the Antiquities Act. See id.; see also Administration of Coral Reef Resources in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, 24 Op. O.L.C. 183, 8–10 (2000). Prior to that decision, the only court to opine on the Antiquities Act’s application beyond the territorial sea was the Fifth Circuit, which reached the opposite conclusion. See Treasure Salvors, Inc. v. Unidentified Wrecked and Abandoned Sailing Vessel, 569 F.2d 330 (5th Cir. 1978). and, most recently, whether the president may revoke or reduce a prior monument designation.18See Hopi Tribe v. Trump, No. 17-cv-02590 (D.D.C. filed Dec. 5, 2017).

Controversies Over Designations

As mentioned above, the Antiquities Act ostensibly imposes a size limit on monument boundaries, but only under vague terms.1954 U.S.C. § 320301(b). Thus, presidents have enjoyed a great deal of discretion in setting monument boundaries.

Critics of that discretion have found some evidence that Congress expected the law to be more constraining. After a proposed 320-acre limit was replaced with the “smallest area compatible” requirement,20 “Smallest area compatible” was a compromise between the strict limits proposed in earlier drafts and the Department of Interior’s push for presidential authority to establish national parks. See Mark Squillace, The Monumental Legacy of the Antiquities Act of 1906, 37 Georgia L. Rev. 473, 478–85 (2003). Congressman John Stephens of Texas asked Congressman John Lacey of Iowa, the law’s House sponsor, “How much land will be taken off the market in the Western States by the passage of the bill?” The answer: “Not very much. The bill provides that it shall be the smallest area necessary for the care and maintenance of the objects to be preserved.” Unsatisfied, Congressman Stephens asked whether it “would be anything like the forest-reserve bill, by which seventy or eighty millions acres of land in the United States have been tied up?” “Certainly not,” Congressman Lacey replied.21See 40 Cong. Rec. S7888 (daily ed. June 5, 1906).

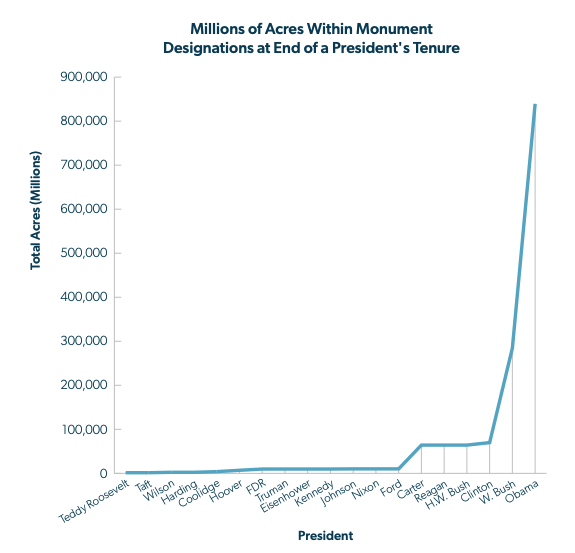

History has not treated that prediction well, as the area designated under the Antiquities Act has eclipsed seven hundred million acres—ten times the area Congressman Lacey thought would “certainly not” be approached.22See Press Release, Dep’t of Interior, Interior Department Releases List of Monuments Under Review, Announces First-Ever Formal Public Comment Period for Antiquities Act Monuments (May 5, 2017), https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-department-releases-list-monumentsunder-review-announces-first-ever-formal; Nat’l Park Serv., Antiquities Act: 1906–2006: maps, facts, & figures, https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/monumentslist.html That area has grown in fits and starts, rather than gradually. And most of the increase has been after celebration of the law’s centenary, attributable to Presidents Bush and Obama’s post-2006 practice of applying the Antiquities Act to the ocean floor beyond the territorial sea and designating several exceedingly large offshore monuments.23See McElfish, supra n.1, at 10,195–96 (suggesting that the total is misleading because of the “new phenomenon” of marine monuments). But even excluding ocean monuments, presidents have discredited Congressman Lacey’s prediction that the Antiquities Act would “certainly not” affect “anything like” seventy or eighty million acres. Consistent with the overall acceleration in the cumulative area contained within monuments, President Barack Obama set records for both the number of monuments designated by a single president and the area contained within those monuments.24See Charlie Northcutt, Obama’s ‘Historic’ Conservation Legacy Beats Teddy Roosevelt, BBC News (Jan. 4, 2017), available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38311093.

Monument supporters respond that “smallest area compatible” entrusts monument boundaries to the president’s discretion.25See, e.g., John Murdock, Monumental Power: Can Past Proclamations under the Antiquities Act Be Trumped?, 22 Tex. Rev. L. & Pol. 349, 356–57 (2018). The large size of some monuments and the cumulative area affected merely reflect the abundance of historic and scientific resources on federal lands and the area needed to protect them. Moreover, they claim, monument designations lead to economic benefits from tourism and outdoor recreation that often exceed the costs of forgone commercial uses.26See, e.g., Headwaters Economics, The Economic Importance of National Monuments to Communities (2017), available at https://headwaterseconomics.org/public-lands/protected-lands/national-monuments/.

Congressional Responses to Perceived Presidential Overreach

As is often the case for contested political issues, the president’s use of the Antiquities Act has followed the second law of thermodynamics. After each period in which the president is perceived as pushing the boundaries of the law, Congress responds in the opposite direction (albeit usually modestly).

In 1943 President Franklin D. Roosevelt designated 210,000 acres as the Jackson Hole National Monument.27Proclamation No. 2578, 57 Stat. 731 (1943) Thirty-three thousand of those acres were given by John D. Rockefeller Jr. to be preserved as part of Grand Teton National Park.28See Matthew W. Harrison, Legislative Delegation and the Presidential Authority: The Antiquities Act and the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument—A Call for a New Judicial Examination, 13 J. Envtl. L. & Litig. 409, 420 (1998). However, Wyoming opposed the plan and any legislation to expand Grand Teton, citing concerns that converting more private land to federal control would shrink the local tax base and forfeit state authority over fishing and gaming.29 See id. Unable to achieve his goals legislatively, President Roosevelt acted unilaterally by designating the monument in the face of congressional opposition.

Wyoming’s delegation responded by introducing legislation to abolish the monument, which FDR vetoed after it passed both chambers of Congress.30H.R. 2241, A Bill to Abolish the Jackson Hold National Monument (1943). The state also sued to overturn the monument.31Wyoming v. Franke, 58 F.Supp.890 (D. Wy. 1945). Both efforts failed, but the controversy continued to simmer for another seven years, during which time Congress barred the expenditure of any funds on the monument.32S. Rep. No. 81–1938, at 4 (1950). In 1950 Congress and the president finally reached a compromise, agreeing to incorporate the monument lands into an expanded Grand Teton National Park and a neighboring elk refuge while amending the Antiquities Act to prohibit any future monument designations in the state.33 See Squillace, supra n.2, at 498. Some of the individuals who led the opposition later indicated their belief that the action had been a mistake. See id. at 498 n.159. It’s impossible to know whether those individuals’ views are representative of other opponents. But that opposition may explain why the eventual compromise allowed for Grand Teton’s expansion while prohibiting additional monuments, a limitation that remains in place a half-century later.

The next major controversy concerned President Jimmy Carter proclaiming seventeen national monuments on a single day (December 1, 1978), all in Alaska, and covering a total of fifty-six million acres.34See id. at 502. Because of the unprecedented sizes of several of those monuments, the day’s designations nearly quintupled the area contained within monuments over the previous seventy-four years. The proclamations drew sharp protests from Alaskans, who feared the impact of taking so much land out of productive use. Protesters engaged in demonstrations throughout the state, including the Great Denali-McKinley Trespass, in which more than 2,500 Alaskans camped, hunted, snowmobiled, and engaged in other activities on monument lands in violation of regulations.35See Sturgeon v. Frost, 136 S. Ct. 1061, 1066 (2016).

Ultimately, Congress intervened by enacting the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, which determined how several hundred million acres of Alaskan federal lands would be designated.3616 U.S.C. § 3101 et seq. That law also forbids the president from making any future withdrawals of federal lands of more than five thousand acres without Congress’s approval.3716 U.S.C. § 3213(a). The provision generally is understood to prohibit large monument designations in Alaska, consistent with the provision being adopted in response to controversial designations. See, e.g., Adam M. Sowards, Reckoning with History: The Antiquities Act Quandary, High Country News (Feb. 22, 2018), available at https://www.hcn.org/articles/reckoning-with-history-the-antiquities-act-and-federal-checks. In theory, the president could designate a monument without withdrawing any land, establishing a monument in name only. See Brent J. Hartman, Extending the Scope of the Antiquities Act, 32 Pub. Land and Res. L. Rev. 153 (2011) (arguing that the president should seek to expand his Antiquities Act authority in a variety of novel ways, including that one). But no such designation has ever been tried, and it would arguably conflict with Congress’s intent in enacting the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act.

Controversy Over Monument Modifications

The controversy over two more-recent national monuments marries concerns over the size of monuments with a new question about the president’s authority to shrink controversial monuments. In 1996 President Bill Clinton designated the nearly 1.9 million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah.38 Proc. No. 6920, Establishment of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (Sept. 18, 1996). The designation was controversial both for the monument’s size and the lack of local input.39 See Eric C. Rusnak, Note, The Straw That Broke the Camel’s Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act, 64 Ohio St. L.J. 669 (2003). Congressman Bill Orton of Utah, a Democrat, described it as “going around Congress and involving absolutely no one from the state of Utah in the process.”40Stephen Chapman, Clinton’s Utah Moment, Chicago Trib. (Sept. 26, 1996), available at https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm1996–09–26–9609260004-story.html. With no local representatives present at the signing ceremony in Arizona’s Grand Canyon featuring celebrities, out-of-state politicians, and activists, President Clinton proclaimed the monument.41 See id. (The signing photo op featured “plenty of dignitaries at the ceremony, including Robert Redford, the governor of Colorado and a Cabinet secretary from Arizona, but not a single elected official from Utah.”)

Two decades later, President Obama declared the 1.35 million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, also in Utah, with the support of tribal organizations and leaders but not local political leaders.42Proc. Establishment of the Bears Ears National Monument (Dec. 28, 2016), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-pressoffice/2016/12/28/proclamation-establishment-bears-ears-national-monument. Prior to the designation, the state’s congressional delegation proposed legislation to designate part of the area as wilderness while allowing resource extraction in other parts, which it characterized as a compromise.43See Amy Joi O’Donoghue, Bishop Staffer: Push for Bears Ears Monument Is ‘Dishonest’, KSL.com (Jun. 15, 2016). Ultimately, the president decided against engaging with Congress and in favor of unilateral action under the Antiquities Act.44See Michelle Cottle, Keeping the President’s Hands Off Utah’s Land, The Atlantic (Sept. 9, 2016), available at https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/09/utah-public-lands-rob-bishop/499316/ (noting that Utah’s delegation “received zero feedback from the administration” on the proposed legislation).

What makes Grand Staircase and Bears Ears unique is that they did not evoke a response from Congress (or at least haven’t yet). Instead, the pendulum was swung back by the president himself. Donald Trump criticized the monuments during his presidential campaign and, once elected, announced they would be reduced by 50 and 85 percent, respectively.45Proc. Modifying the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (Dec. 4, 2017), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidentialactions/presidential-proclamation-modifying-grand-staircase-escalante-national-monument/; Proc. Modifying the Bears Ears National Monument (Dec. 4, 2017), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-proclamation-modifying-bears-earsnational-monument/. It was the first time a president had reduced a national monument since 1964, and it removed more land than earlier reductions (although not as a percentage of the original designation).46See Robert Rosenbaum et al., The President Has No Power Unilaterally to Abolish of Materially Change a National Monument Designation under the Antiquities Act of 1906 (May 3, 2017), available at https://naturalresources.house.gov/imo/media/doc/Updated%20Arnold%20and%20Porter%20Memo%20on%20Presidential%20Power%20and%20National%20Monuments.pdf.

The downsizing of Grand Staircase and Bears Ears was controversial even before it was announced. Supporters of both monuments, including tribal groups, conservation groups, and outdoor-gear companies, contested the president’s power to modify the monuments, especially so significantly (which they viewed as akin to de facto revocation).47See id.; see also William Cummings, ‘The President Stole Your Land,’ Patagonia Homepage Says, USA Today (Dec. 4, 2017), available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2017/12/04/anti-trump-patagonia-message/921542001/. They argue that the Antiquities Act authorizes the president only to “proclaim” monuments and omits any explicit authorization to modify or revoke existing ones, and they note that none of the prior reductions were challenged in court.48See Squillace et al., supra n. 13, at 57–59. Although not concerning the Antiquities Act, this argument is arguably supported by a recent district court decision interpreting another statute, although that decision is under review by the Ninth Circuit. See League of Conservation Voters v. Trump, No. 17-cv-00101 (D. Ak. Mar. 29, 2019) (interpreting the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act). The opponents also argue that any such authority is inconsistent with the law’s purpose of protecting vulnerable resources, relying in part on the attorney general’s opinion of 1938 (while disagreeing with its conclusion that monument reductions are permissible).49Id. at 58–59. Finally, they argue that Congress foreclosed any such authority implicitly in 1972 with the passage of the Federal Land Policy Management Act.50Id. at 59–64.

Supporters of such presidential power respond that courts routinely interpret delegations of discretionary executive authority to include the power to reverse prior decisions, such as when Congress authorizes an agency to issue regulations without addressing the repeal or amendment of regulations.51See Yoo and Gaziano, supra n. 11, at 639–47. They also note that courts are skeptical of statutory interpretations that conflict with longstanding practice, such as presidents’ repeatedly reducing monuments without anyone questioning that authority for more than a half-century.525\ See id. at 659–60. Finally, they note that when Congress wants to make protections for a monument permanent, it does so by converting the land into a national park that can be changed only by Congress.53 See Todd Gaziano and Jonathan Wood, The Antiquities Act’s Loose Limits Cut Both Ways, Yale J. on Reg. Notice & Comment (Aug. 22, 2018), available at http://yalejreg.com/nc/the-antiquities-acts-loose-limits-cut-both-ways-by-todd-gaziano-and-jonathan-wood/.

Lawsuits have been filed against the reductions of both Grand Staircase and Bears Ears.54See, e.g., Hopi Tribe v. Trump, No. 17-cv-02590 (D.D.C. filed Dec. 5, 2017). The author represents recreationists, ranchers, and others as intervenors defending the president’s power to reverse national monuments. So courts may soon resolve the question. If the courts uphold the president’s authority, that may prompt Congress to enter the fray once again.

Lessons from Past Reforms

It often is asserted that without the Antiquities Act’s broad power, the federal government would be unable to protect federal lands since other avenues of protection, such as congressional action, are too slow.55Paradoxically, that argument also is made against the president’s power to modify existing monuments. McElfish, supra n.1, at 10,197. If a monument’s purpose is to preserve the status quo and give Congress time to act, an extended period of inactivity suggests that Congress does not see any emergency to resolve. Yet little has been written about what has happened in Wyoming and Alaska since the president’s authority to designate national monuments there was curtailed. Reforms in those states can provide a lens through which to analyze potential future reforms.

How have federal lands in those two states been managed? In Wyoming, the president may not designate national monuments, but Congress may do so. Yet it has exercised that power just once—a half-century ago. In 1972 it established the Fossil Butte National Monument in Wyoming, reserving 8,200 acres to protect rare fossils.56See Encyclopedia Brittanica, Fossil Butte Nat’l Monument, https://www.britannica.com/place/Fossil-Butte-National-Monument. In Alaska, presidents may withdraw up to 5,000 acres for national monuments, but they have declined to do so: no national monuments have been designated in that state since 1980.

The federal land designation most similar to recent large monument designations is wilderness area, which requires legislation. It turns out that Congress has been more active in designating wilderness areas in Wyoming and Alaska than in states where the Antiquities Act continues to apply with full force. For instance, Congress has designated more than 3,068,469 acres in Wyoming as wilderness areas since 1950, more than a tenth of Wyoming’s 30,013,219 million acres of federal lands.57See Univ. of Montana, Wilderness Areas of the United States, https://umontana.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=a415bca07f0a4bee9f0e894b0db5c3b6. Compare that to Oregon, the state most like Wyoming in terms of total acreage and percentage of land in federal ownership.58Wyoming has 30,013,219 acres of federal land, 48.1 percent of the land in that state. Oregon has 32,621,631 acres of federal land, 52.9 percent of the land in that state. Two national monuments have been designated in Oregon since 1954, the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument and the Newberry National Volcanic Monument, both established by Congress. See New Leader Picked for Fossil Beds, Blue Mountain Eagle ( June 20, 2012), available at https://www.bluemountaineagle.com/news/new-leader-picked-for-fossil-beds/article_73a0dc57–164e-5a74–94b8-d66b2d08c9fa.html; Gerald W. Williams, Ph.D., National Monuments and the Forest Service (Nov. 18, 2003), available at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/fs/monuments.html. In 2017 President Obama controversially expanded Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, which straddles the border between Oregon and California. See Presidential Proc., Boundary Enlargement of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument (Jan. 12, 2017), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/12/presidential-proclamation-boundaryenlargement-cascade-siskiyou-national. Congress has designated just 2.4 million acres as wilderness in that state, about 7.5 percent of the state’s federal lands.59See Wilderness Areas of the United States, supra n.57.

Alaska cannot easily be compared to any other state, as it has nearly four times as much federal land as the second-place state (Nevada). However, as in Wyoming, Congress has been involved actively in managing Alaskan federal lands. It has designated nearly sixty-four million acres as wilderness areas, nearly 30 percent of federal lands within that state.60See id.

Taken together, the foregoing examples suggest that less reliance on presidential action translates into greater congressional engagement in federal land management. That outcome shouldn’t surprise anyone. The legislative process is, by design, cumbersome. When Congress delegates broad power to the executive branch, as it did under the Antiquities Act, such delegation reduces the likelihood that Congress will undertake the effort required to legislate further.61 That phenomenon is not unique to the Antiquities Act but is reflected in the general growth of the executive power during the twentieth century. See Christopher J. Walker, Inside Agency Statutory Interpretation, 67 Stan. L. Rev. 999, 1000 (2015) (describing the role of lawmaking shifting from Congress to administrative agencies, along with judicial deference to bureaucratic expertise). Limiting executive authority, by contrast, logically would spur Congress to take more interest in federal land management.

As noted, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act prohibits unilateral withdrawals of more than five thousand acres, thus limiting large designations without affecting more-targeted ones.62See 16 U.S. Code § 3213. Conceivably, the president could circumvent that limit by designating several monuments just under the five-thousand-acre threshold that cumulatively exceed it. Yet such circumvention has not occurred.

In fact, no monuments of any size have been designated in Alaska since the exemption was put in place, despite controversies over the use of lands in the state.63See, e.g., The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Drilling Controversy, Explained, Vox.com, https://www.vox.com/ad/16482242/arctic-nationalwildlife-refuge-drilling-controversy-explained (describing the failed push to designate part of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as a national monument to prevent drilling). Such evidence suggests that an acreage limit can be an effective way of constraining executive discretion without eliminating it entirely, whether the goal is to limit initial monument designations or subsequent modifications thereof.

Finally, have the Alaska and Wyoming exemptions led to precious resources being lost in those states, as some predict for any change to the Antiquities Act? Proving a negative—the absence of such losses—always is difficult. But I suspect the answer is no. First, strong incentives exist to notice and publicize such losses to further the argument that the Antiquities Act should be preserved or its exemptions repealed, but cases of unusual resource damage have not been identified in these states.

The reason likely is because other federal laws enacted since the Antiquities Act have reduced the risk that federal resources will be destroyed before Congress or the executive branch could act.64Glen Canyon is often cited to demonstrate the need for swift presidential action under the Antiquities Act. See, e.g., John Weisheit, Escalante National Monument: A History of the First Proposal, OnTheColorado.com (Aug. 27, 2008), available at http://www.onthecolorado.com/articles.cfm?mode=detail&id=1219881501520. At one time proposed as part of a monument, Glen Canyon was flooded by the construction of Glen Canyon Dam. See id. But it’s not clear what the takeaway from this example should be. First, nothing barred the president from using the Antiquities Act to protect it; he simply made a political calculus not to. See id. Second, the dam was authorized and funded by Congress, which could have overridden a monument designation anyway despite environmentalist objections. See Arizona State University, Glen Canyon Dam, http://grcahistory.org/sites/beyond-park-boundaries/glen-canyon-dam/. Finally, the case predates the 1970s-era conservation laws often cited by monument critics. See id. (Congress approved the dam in 1956.)The Archaeological Resources Protection Act, for instance, forbids excavation or removal of archaeological resources from any federal land without a permit and limits the circumstances wherein permits may be granted.6516 U.S.C. §§ 470aa-479mm. It also imposes harsher penalties on violations than does the Antiquities Act (a maximum $100,000 fine and five years’ imprisonment versus a maximum $500 fine and ninety days’ imprisonment). For that reason, the Forest Service has described the Archaeological Resources Protection Act as “replac[ing] the Antiquities Act” for the purpose of protecting historic artifacts.66See U.S. Forest Serv., Laws, Regulations and Executive Orders Authorizing Historic Preservation, https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r1/learning/history-culture/?cid=stelprdb5335841.

Conceivably, limits on the president’s monument-proclamation power could make such resources more vulnerable by reducing awareness of them. If that were so, Wyoming and Alaska should have experienced more violations of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act than they have. Only one of the forty-one published cases concerning the enforcement of that act has come from those states, suggesting that damage to such resources is no more acute than in states where the Antiquities Act’s application is not limited.67See United States v. Lynch, 233 F.3d 1139 (9th Cir. 2000) (overturning conviction from District of Alaska). Indeed, a 1987 Government Accountability Office report concluded that looting remains a serious problem in the Four Corners states, but it did not identify a lack of regulatory tools as a source of that problem.68See Government Accountability Office, Report, Problems Protecting and Preserving Federal Archaeological Resources (1987), available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/150/145926.pdf. The report does not imply that looting is not a problem in other areas but focuses on the Four Corners states because their climate better preserves ancient artifacts and more such artifacts have been identified in these states. See id. at 2. Instead, the primary challenges are the lack of a catalogue of existing resources and funding adequate to enforce existing laws over the vast federal estate, neither of which necessarily is helped by designating a monument.69 Lack of funding for federal land management is a pervasive problem. For instance, the National Park System, despite its popularity, faces an $11.6 billion maintenance backlog. See Statement of Lena McDowall, Deputy Dir. for Management and Admin, Nat’l Park Serv., U.S. Dept. of Interior, Before the Senate Energy & Nat. Res. Comm., Regarding the Deferred Maintenance and Operational Needs of the Nat’l Park Serv. (Apr. 17, 2018), available at https://www.doi.gov/ocl/nps-maintenance-backlog.

Those laws are not limited to archaeological resources either. Another law broadly prohibits anyone from willfully damaging any federal property.7018 U.S.C. § 1361. That law prohibits, among other things, any damage or alteration of federal land, such as felling or burning timber, altering streams or wetlands, and harming other environmental resources.71See, e.g., United States v. Robertson, No. 16–30178 (9th Cir. 2017) (upholding conviction for “damaging” national forest lands by digging a pond without a permit). That law, too, imposes harsher penalties than does the Antiquities Act, allowing up to ten years’ imprisonment and a fine of $250,000 if the damage to federal property exceeds $1,000.72See 18 U.S.C. §§ 1361, 3571(b).

Some federal laws on the books are designed to prevent such damage rather than punishing it after the fact. They include the Federal Land Policy Management Act and National Environmental Policy Act, which require extensive review before any activity on federal land that may affect the environment adversely can be permitted. The former act, for instance, directs federal agencies to steward lands under their control “in a manner that will protect the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resources, and archaeological values,” including, where appropriate, preserving lands “in their natural condition” for the benefit of wildlife and outdoor recreation.7343 U.S.C. § 1701. The Federal Land Policy Management Act pursues that goal by requiring agencies to develop management plans for federal lands and designate which uses may be allowed and how they will be regulated to protect resources.74See, e.g., 43 U.S.C. §§ 1712–1714. It also allows the secretary of the interior temporarily to withdraw federal lands from certain uses, giving Congress time to make the withdrawals permanent or designate the lands in some other way.75See 43 U.S.C. § 1714.

The National Environmental Policy Act requires agencies to analyze the environmental impacts of the projects they undertake, requires public comment on those impacts, and requires analysis of alternatives that could avoid or mitigate them.76See Council on Environmental Quality, Citizens Guide to NEPA, https://ceq.doe.gov/get-involved/citizens_guide_to_nepa.html. That law does not prohibit outright projects that affect resources on federal lands negatively but does discourage such projects. It also can delay such projects long enough for the executive branch or Congress to take other steps to protect important resources.77See, e.g., Austin Price, Montana’s Paradise Valley Is More Valuable Than Gold, Sierra (Oct. 10, 2018), available at https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/montana-s-paradise-valley-more-valuable-gold-yellowstone-mining-ban (describing the controversy over proposed mining plans in Paradise Valley and the secretary of interior’s decision to withdraw the area from mining to block those plans).

In summation, past legislative responses to perceived presidential overreach under the Antiquities Act suggest that reducing presidential discretion encourages congressional engagement on federal land-management issues. They also dispel the concern that the president will simply circumvent any limit on his discretion by, for instance, doing piecemeal what Congress forbids doing en masse. Finally, the lack of evidence that past reforms have jeopardized archaeological and scientific resources should quiet fears that future reforms will cause the sky to fall.

The Antiquities Act’s Future

Presidential power under the Antiquities Act currently is the subject of criticism from groups that ordinarily find little common ground. To critics of large monument designations, the president enjoys too much discretion to designate monuments wherever he wishes and as large as he wishes. Monument supporters, by contrast, oppose similarly broad discretion (or, in some cases, any discretion at all) to modify or revoke existing monuments.

The controversies suggest the possibility of future legislative reforms, whether addressing the concerns of one side or the other or achieving a grand compromise. In any case, past legislative reforms provide a useful lens for analyzing the effects of additional reforms. Among other things, the experiences of Wyoming and Alaska suggest that more-constrained executive discretion in establishing or modifying monuments could entice Congress to be more active in managing federal lands.

Such incentives could be strengthened further by tailoring any future reforms to encourage congressional engagement. They could, for instance, require monument designations or modifications over a certain size threshold to be submitted to Congress for review or approval.78This could require affirmative approval or trigger a streamlined process for Congress to disapprove a proposed monument proclamation or modification. Compare Congressional Review Act, 5 U.S.C. §§ 801–08 (requiring agencies to submit rules to Congress and establishing a streamlined process for Congress to review rules) with Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act of 2019, S.92, 116th Cong. (2019) (proposing to require affirmative congressional approval for certain rules). Once a monument is proclaimed, changes could be prohibited or limited for a predetermined period, giving Congress an opportunity to decide whether to protect the land as a national park, wilderness area, or other designation permanently or whether to do nothing and allow the president to modify the monument after the time window closes.79Congress has upgraded many monuments to national parks but lacks any trigger to incentivize it to consider such action quickly after a monument has been proclaimed. See McElfish, supra n.1, at 10,195–97.

Such congressional engagement offers numerous benefits over the status quo. Beyond structural separation-of-powers concerns, legislative compromises tend to be less controversial and therefore more enduring.80As an example, Congress passed a bipartisan bill designating 1.3 million acres of wilderness, expanding several national parks, and creating five national monuments. See Matthew Daly, Congress Approves Major Public Lands, Conservation Bill, Associated Press (Feb. 26, 2019), available at https://www.apnews.com/27b092f5988441d1aa511cb95ede993e. In light of the bill’s broad support, even among critics of the Antiquities Act, it is exceedingly unlikely to generate the sort of long-simmering controversy that some presidential designations have. See id. (quoting Congressman Rob Bishop of Utah as saying the bill “establishes national monuments ‘the right way,’ through congressional action rather than executive order”). They also reflect greater public participation and deliberation, the absence of which has been a major source of criticism for both large monument designations and significant reductions in them.81The president’s broad discretion allows monuments to be proclaimed or not (and perhaps modified or not) for any reason appealing to him. Because of the lack of public process and deliberation, such decisions are commonly criticized as politically motivated, particularly as serving the interests of special interests rather than the public good. See, e.g., Sen. Mike Lee, Utahns Fear Obama Will Heed Environmentalists, Not Them, on National Monument Designation, Daily Signal (Sept. 26, 2016), available at https://www.dailysignal.com/2016/09/26/utahns-fear-obama-willheed-environmentalists-not-them-on-national-monument-designation/; Chris D’Angelo, Trump’s Monument Review Was a Big Old Sham, Grist. com (Mar. 16, 2019), available at https://grist.org/article/trumps-monument-review-was-a-big-old-sham/. Ultimately, greater congressional engagement would increase political accountability for these decisions.

Independent Women’s Forum

Independent Women’s Forum