Introduction

The Antiquities Act of 1906 gives the president of the United States unilateral authority and broad discretion to create national monuments on federal lands. The act’s original purpose was to protect objects of historical, cultural, or scientific significance located on federal lands. The act stipulates that monuments must be kept to the smallest area sufficient for protecting the objects of interest. Although Congress can create national monuments through the legislative process, presidents also have authority to designate national monuments by issuing proclamations.1 54 U.S.C. § 320301a (2018).

The Antiquities Act has been crucial for preserving many of America’s most popular public lands. The original intention of the Antiquities Act was to preserve objects on federal lands in danger of destruction.2Richard West Sellars, “A Very Large Array: Early Federal Historic Preservation – The Antiquities Act, Mesa Verde, and the National Park Service Act,” Natural Resources Journal 47, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 267–328 In practice, however, presidents have used the act to set aside large areas of land that are much like nation- al parks. Many of the national parks in existence today were first designated as national monuments by presidential proclamation and later redesignated as national parks by Congress.3National monuments and national parks have become functionally similar in recent decades. Many national monuments are signicantly larger than some of the most popular national parks. The National Park Service oversees national parks, but there are several agencies that oversee national monuments, depending on the circumstances. Only Congress can designate national parks, but Congress or the president can establish national monuments.

In recent years, the Antiquities Act has become the center of controversy over presidential discretion and the management of federal lands.4Mark Squillace, “The Monumental Legacy of the Antiquities Act of 1906,” Georgia Law Review 37, no. 2 (Winter 2003): 473–610. In 1996, President Clinton established Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and President Obama created Bears Ears National Monument in 2016. Both designations were controversial because of their sizes and locations.5Katy Steinmetz, “Donald Trump’s Move to Shrink Two National Monuments Sets Stage for Battle over 111-Year-Old Law,” Time, December 5, 2017. In 2017, President Trump reduced the sizes of both national monuments.6Proclamation No. 9681, 82 Fed. Reg. 58081 (December 4, 2017); Proclamation No. 9682, 82 Fed. Reg. 58089 (December 4, 2017). These actions have renewed scholarly interest in the extent of executive discretion under the Antiquities Act.

All public policies require some element of discretion, and determining the amount of discretion appropriate for a particular situation involves weighing trade-offs between predictability and autonomy. With greater discretion, there is greater flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances or public sentiments. However, flexibility often reduces the predictability of outcomes and may also create the potential for abuse of executive power. If executive discretion is restricted, some flexibility is sacrificed for more predictability. In terms of the Antiquities Act, clearly defining the extent of executive discretion may be desirable to reduce abrupt policy changes in favor of predictability and reduce controversy in favor of cooperation.

In this policy paper, we provide a brief review of the relevant literature on the extent of executive discretion under the Antiquities Act. This discussion is not a comprehensive legal analysis, but does review the key findings of legal scholars. We begin by outlining the history of the Antiquities Act. In particular, we examine how Congress’s decision to leave many of the law’s key terms without clear definitions has led to the broad use of executive discretion in designating national monuments. Next, we discuss the general deference that courts have afforded the president in declaring national monuments. Such deference, combined with the act’s lack of clearly defined terms, has allowed the chief executive to exercise wide discretion.

In response to recent controversy, legal scholars have analyzed executive discretion under the Antiquities Act, but no clear consensus has emerged about what the act allows presidents to do and where that authority ends. After reviewing the existing literature, we suggest potential steps Congress could take to define the limits of the Antiquities Act clearly. To clarify the scope of executive discretion, Congress could act to (1) increase congressional oversight, (2) prevent presidents from unilaterally reducing the size of national monuments or rescinding them altogether, and (3) require consultation with relevant stakeholders. These changes would likely lead to more cooperative management of public lands by increasing predictability and providing clarity regarding the legal extent of executive discretion under the Antiquities Act.

Executive Discretion and the History of the Antiquities Act

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the federal government followed a policy of disposing of public lands in the West to facilitate the region’s development. Congress created the General Land Office (GLO) to manage the divestment of public lands.7 Brent J. Hartman, “Extending the Scope of the Antiquities Act,” Public Land and Resources Law Review 32 (2011): 153–92.

However, as land was allocated to private uses and settled at the end of the nineteenth century, some members of Congress, archaeologists, and GLO employees vocalized their concerns about the preservation of Native American sites. Such sites frequently were vandalized and subject to profiteering.8Richard West Sellars, “A Very Large Array: Early Federal Historic Preservation—the Antiquities Act, Mesa Verde, and the National Park Service Act,” Natural Resources Journal 47, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 267–328. Leadership in the Department of the Interior likewise had been pushing for expanded executive authority for conservation purposes. In 1904, GLO Commissioner William A. Richards wrote to Secretary of the Interior Ethan Hitchcock, saying, “What is needed is a general enactment, empowering the President to set apart, as national parks, all tracts of public land which . . . [are] desirable to protect and utilize in the interest of the public.”9W. A. Richards, Commissioner, General Land Office, to Secretary of the Interior, 5 October 1904, tray 165, National Monuments, NPS, RG 79, NA.

Although the GLO commissioner wanted the president to have the power to create national parks, some conservation-friendly members of Congress disagreed. For instance, Representative John F. Lacey of Iowa wrote to Secretary Hitchcock on April 19, 1900, stating that “it would not be wise to grant authority in the Department of the Interior to create national parks generally, but that it would be desirable to give the authority to set apart small reservations, not exceeding 320 acres each, where the same contained cliff dwellings and other prehistoric remains.”10Robert Claus, Information about the Background of the Antiquities Act of 1906, May 10, 1945 (on deposit with Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation of the National Park Service); See also Squillace, “Monumental Legacy.”

Representative Lacey worked with archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett to draft the original version of the Antiquities Act, which Lacey introduced in Congress in January 1906.11Sellars, “Very Large Array”; Hartman, “Extending the Scope.” Early drafts of the bill contained a proposed size limit of 320 acres for national monuments. That limit expanded to 640 acres in subsequent versions of the bill. The wording of the final bill, however, stated only that monuments must be “confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”12Sellars, “Very Large Array”

Many members of Congress were hesitant to support the Antiquities Act in 1906 because they feared that the federal government would restrict access to large tracts of federal land and eliminate any chance of further divestment. In a congressional debate on June 5, 1906, Representative John Stephens of Texas asked Representative Lacey whether the bill “would be anything like the forest-reserve bill, by which seventy or eighty million acres of land in the United States have been tied up.” Lacey replied, “Certainly not. The object [of the Antiquities Act] is . . . to preserve these old objects of special interest and the Indian re- mains in the pueblos in the Southwest.”13 40 Cong. Rec. 7888 (daily ed. June 5, 1906). With Representative Lacey’s assurances, the bill quickly passed the House and the Senate, and was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906. 1440 Cong. Rec. H7888 (daily ed. June 5, 1906); 40 Cong. Rec. H8038 (daily ed. June 7, 1906); 40 Cong. Rec. S8042 (daily ed. June 8, 1906); 40 Cong. Rec. S8240 (daily ed. June 11, 1906).

The Antiquities Act of 1906 allows presidents to create national monuments without the consent of Congress, and it lays out three requirements for presidential national monument designations. National monuments must

- include “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, [or] other objects of historic or scientific interest”;

- be located on land that is owned or controlled by the federal government; and

- not exceed “the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”1554 U.S.C. § 320301a (2018).

When Congress passed the Antiquities Act, the law did not define key terms, including “historic or scientific interest” and “smallest area compatible with proper care and management.” The final language of the bill did not provide concrete guidance on what constitutes the “smallest area” necessary to protect particular antiquities.16Sellars, “Very Large Array” Instead, decisions about how large a national monument should be were left largely to the discretion of the president. As a result, the creation of many national monuments has resulted in hundreds of thousands of acres of land being designated. In at least 23 cases, more than a million acres were designated as a national monument.17“Antiquities Act, 1906–2006: Maps, Facts, & Figures,” Monuments List tab, Archaeology Program, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, last updated May 23, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/MonumentsList.htm.

Monuments that were designated at over a million acres include Katmai, Glacier Bay, Death Valley, Admiralty Island, Becharof, Bering Land Bridge, Denali, Gates of the Arctic, Kobuk Valley, Misty Fjords, Noatak, Wrangell-St. Elias, Yukon-Charley Rivers, Yukon Flats, Grand Staircase-Escalante, Grand Canyon-Parashant, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (Papahānaumokuākea), Rose Atoll, Pacific Remote Islands, Marianas Trench, Mojave Trails, Northeast Canyons and Seamounts, and Bears Ears.

At the time the Antiquities Act was passed, few other conservation laws were in place. Ten years would pass before the National Park Service was created.18“Quick History of the National Park Service,” National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, last updated May 14, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/articles/quick-nps-history.htm. Congress granted presidents the authority to create national monuments to allow for quick action to preserve sites in danger of imminent destruction. Originally, the Antiquities Act was written to protect “landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest”; it imposed a penalty on anyone who damages or destroys “any historic or prehistoric ruin or monument, or any object of antiquity” on federal lands.1954 U.S.C. § 320301a (2018); 16 U.S.C. 431-433

However, because Congress did not define what “objects of historic or scientific interest” meant, the definition of “antiquities” broadened quickly to include unique geological sites,20An example is Grand Canyon National Monument, designated by Proclamation No. 794, 35 Stat. 2175 ( January 11, 1908). paleontological objects,21An example is Petrified Forest National Monument, designated by Proclamation No. 697, 34 Stat. 3266 (December 8, 1906). and other areas of historical or scenic significance.22An example is Craters of the Moon National Monument, designated by Proclamation No. 1694, 43 Stat. 1947 (May 2, 1924). Theodore Roosevelt was the first president to use the Antiquities Act, and some of the earliest objects that were protected were both archaeological and geo- logical. For example, from 1906 to 1908, some of President Roosevelt’s geological designations included Devils Tower in Wyoming, Jewel Cave in South Dakota, and Natural Bridges in Utah. He set a precedent for a broad interpretation of the act in the early part of the twentieth century; that broad interpretation has continued into the twenty-first century. The Antiquities Act was used to conserve some of America’s most iconic locations, including the Grand Canyon, Death Valley, Zion, and Glacier Bay, among many others.23Francis P. McManamon, “The Antiquities Act and How Theodore Roosevelt Shaped It,” Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal 32, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 24–38. Over the years, Congress redesignated or incorporated 32 presidentially created monuments into national parks.24“Monuments Protected under the Antiquities Act,” National Parks Conservation Association, January 13, 2017, https://www.npca.org/resources/2658-monuments-protected-under-the-antiquities-act. “National Park System, “ National Park Service. 2019. https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/national-park-system.htm; The presidentially designated national monuments that were later turned into national parks are Petrified Forest, Cinder Cone, Lassen Peak, Grand Canyon, Grand Canyon II, Pinnacles, Mount Olympus, Mukuntu-weap/Zion, Zion “II” (Kolob Section), Sieur de Monts, Katmai, Lehman Caves, Bryce Canyon, Carlsbad Cave, Glacier Bay, Arches, Great Sand Dunes, Death Valley, Saguaro, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Fort Jefferson, Joshua Tree, Capitol Reef, Channel Islands, Jackson Hole, Marble Canyon, Denali, Gates of the Arctic, Kenai Fjords, Kobuk Valley, Lake Clark, and Wrangell-St. Elias.

The Antiquities Act does not establish any special procedures for declaring a national monument, and it does not contain any provision for judicial review of designated monuments.25Harold H. Bruff, “Judicial Review and the President’s Statutory Powers,” Virginia Law Review 68, no. 1 (1982): 1–61. Presidents create national monuments by issuing proclamations declaring that certain parcels of federal land henceforth are national monuments. Congress, on the other hand, creates both national monuments and national parks through normal legislative processes. Only Congress can designate national parks.26“Quick History of the National Park Service,” National Park Service, 2018. https://www.nps.gov/articles/quick-nps-history.htm

Judicial Review and the Expansion of Executive Discretion

Because the Antiquities Act itself does not define key terms or provide concrete limits for executive discretion, questions about the legality of particular national monument designations have been left for courts to decide. Although federal courts have issued several minor rulings on the Antiquities Act, four court cases are particularly important in determining the extent of presidential discretion. These four cases are relevant because the judicial branch largely has deferred to executive discretion, especially given that the law itself does not provide guidance about where that discretion ends. These cases, reviewed in this section, are Cameron v. United States, State of Wyoming v. Franke, Anaconda Copper v. Andrus, and Mountain States v. Bush.27Cameron v. United States, 252 U.S. 450 (1920); State of Wyoming v. Franke, 58 F. Supp. 890 (D. Wyo. 1945); Anaconda Copper Company v. Andrus, A79-161 Civ. (D.AI. July 1, 1980); Mountain States Legal Foundation v. Bush, 306 F.3d 1132 (D.C. Cir. 2002).

Cameron v. United States

Less than two years after the passage of the Antiquities Act, President Theodore Roosevelt used the law to create Grand Canyon National Monument, setting aside more than 800,000 acres.28Squillace, “Monumental Legacy.” In conjunction with the new designation, the federal government evicted Ralph H. Cameron from his mining claims on the Grand Canyon’s south rim. Cameron sued the federal government, arguing that his mining claims had been revoked unjustly because the monument exceeded the act’s authority.29Squillace, “Monumental Legacy.”

In 1920, the Supreme Court ruled in Cameron v. United States that the Grand Canyon qualified as an object of historic or scientific interest. The court found that “the act under which the President proceeded empowered him to establish reserves embracing ‘objects of historic or scientific interest.’The Grand Can- yon, as stated in his proclamation, ‘is an object of unusual scientific interest.’”30Cameron, 252 U.S. at 456. The court did offer some potential reasons why the Grand Canyon should be considered an object of scientific interest, stating, “It is the greatest eroded canyon in the United States, if not in the world, is over a mile in depth, has attracted wide attention among explorers and scientists, affords an unexampled field for geologic study, is regarded as one of the great natural wonders, and annually draws to its borders thousands of visitors.”31Cameron, 252 U.S. at 456. But the court’s opinion did not offer any criteria for determining what should qualify as an object of scientific interest and what should not. Thus, the court deferred to the executive branch to determine the meaning of scientific interest in future monument designations.

State of Wyoming v. Franke

In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created Jackson Hole National Monument in Wyoming. The State of Wyoming sued, arguing that Jackson Hole National Monument exceeded the scope of the Antiquities Act because it lacked sites of historic or scientific interest. In State of Wyoming v. Franke, the US District Court for the District of Wyoming upheld the monument’s designation, stating that “whenever a statute gives a discretionary power to any person, to be exercised by him upon his own opinion of certain facts, it is a sound rule of construction, that the statute constitutes him the sole and exclusive judge of the existence of those facts.”32Wyoming, 58 F. Supp. at 890. That interpretation conferred broad authority on the executive branch because Congress had not imposed clear legal constraints on executive action.

Soon after the ruling in Wyoming v. Franke, Congress passed a law to abolish Jackson Hole National Monument, but President Roosevelt vetoed it. In 1947, Congress again attempted to abolish the monument, but public sentiments had changed, making it politically expedient to preserve the monument as designated. In 1950, Congress passed legislation that incorporated the monument into adjacent Grand Teton National Park and amended the Antiquities Act to prohibit any new national monuments in Wyoming without congressional approval.33“Creation of Grand Teton National Park,” National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, 2000, https://www.nps.gov/grte/planyourvisit/upload/creation.pdf. This amendment was the first effort to limit the president’s authority under the Antiquities Act, but it applied only to Wyoming.

Anaconda Copper v. Andrus

In December 1978, President Carter designated 15 large national monuments in Alaska that, collectively, covered more than 54 million acres of land—roughly 15 percent of Alaska’s total land area.34“Antiquities Act, 1906–2006: Maps, Facts, & Figures,” Monuments List tab, Archaeology Program, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, last updated May 23, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/MonumentsList.htm; Alaska’s land area is approximately 365 million acres. Thus, 54 million divided by 365 million yields 14.8 percent. In Anaconda Copper v. Andrus, the US District Court for the District of Alaska did not alter President Carter’s Alaskan monument designations, explaining that “the parameters of presidential authority have not yet been fully defined. The Supreme Court has had the opportunity to do so in the Cameron case and again in Cappaert, but did not do so.”35Ann E. Halden, “The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and the Antiquities Act,” Fordham Environmental Law Journal 8, no. 3 (1997): 713-39; In Cappaert v. United States, federal courts had weighed the authority of the president under the Antiquities Act against private water rights in the context of Devils Hole. Devils Hole was added to the existing Death Valley National Monument in 1952 by President Truman’s executive order. The Cappaerts’ pumping of groundwater reduced the water level in Devils Hole, jeopardizing preservation of the Devils Hole pupfish, which the monument had been established to protect. The courts found that federal water rights antedated those of the Cappaerts. The courts also found that when the federal government creates a monument, by implication, it reserves water rights sufficient to accomplish the monument’s purposes. See Exec. Order No. 2961 (1952) and Cappaert v. United States, 426 U.S. 128 (1976). The court held that “there are limitations on the exercise of presidential authority on the Antiquities Act. The outer parameters have not yet been drawn by judicial decision.”36Anaconda Copper Company v. Andrus, A79-161 Civ. (D.AI. July 1, 1980). See also Ann E. Halden, “The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and the Antiquities Act,” Fordham Environmental Law Journal 8, no. 3 (1997): 713–39.

The controversy over President Carter’s designations sparked a minor change in presidential discretion. Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 (ANILCA), which re- quires Congress to ratify executive action that withdraws more than 5,000 acres of federal land in Alaska.37Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, 43 U.S.C. §§ 1602–1784 (1980). Public land is “withdrawn” when it is withheld “from settlement, sale, location, or entry, under some or all of the general land laws.”3843 U.S.C. § 1702(j) (1976). The mere designation of a monument does not necessarily imply a legal with- drawal, because a president could designate a monument without imposing any restrictions on the area’s use under existing law. Monument proclamations in practice, however, generally include restrictions that have been considered withdrawals.39Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, 16 U.S.C. § 3213 (2018); Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, 43 U.S.C. ch. 35 § 1701 et seq (2018); Richard M. Johannsen, “Public Land Withdrawal Policy and the Antiquities Act,” Washington Law Review 56, no. 3 (1981): 439–65.

Arguably, since ANILCA does not specifically address the Antiquities Act, a future president could designate a national monument in Alaska and claim that the designation does not constitute a withdrawal prohibited by ANILCA. Neither Congress nor the courts have settled whether such an action would meet the legal definition of a withdrawal in the Alaska context. Only one presidentially declared national monument has been created in Alaska since 1978, and it was just under ANILCA’s 5,000-acre limit.40This was the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument, created by Proclamation No. 8327, 73 Fed. Reg. 75293 (December 5, 2008). See also John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act of 2019, Pub. L. No. 116-9 (March 12, 2019); US Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, Foundation Statement—Alaska Unit: World War II Valor in the Pacific, September 2010, https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/Region_7/NWRS/Zone_1/Alaska_Maritime/PDF/Foundationas%20Statement.pdf.

Mountain States v. Bush

A more recent court case has confirmed the federal courts’ ability to review the actions of presidents under the Antiquities Act. In the 2002 case Mountain States v. Bush, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals found that, “although the Supreme Court has never expressly discussed the scope of judicial review under the Antiquities Act, the Court has directly addressed the nature of review of discretionary Presidential decision-making under other statutes.”41Mountain States, 306 F.3d. The D.C. Circuit reaffirmed the ability of the courts to review presidential proclamations to ensure that they are consistent with constitutional principles and that the president has not exceeded his statutory authority. The D.C. Circuit did not spell out those limits, but it did affirm that federal courts can rule whether presidents have acted beyond their legal authority on a case-by-case basis.42Mountain States, 306 F.3d.

Executive Discretion under the Antiquities Act Today

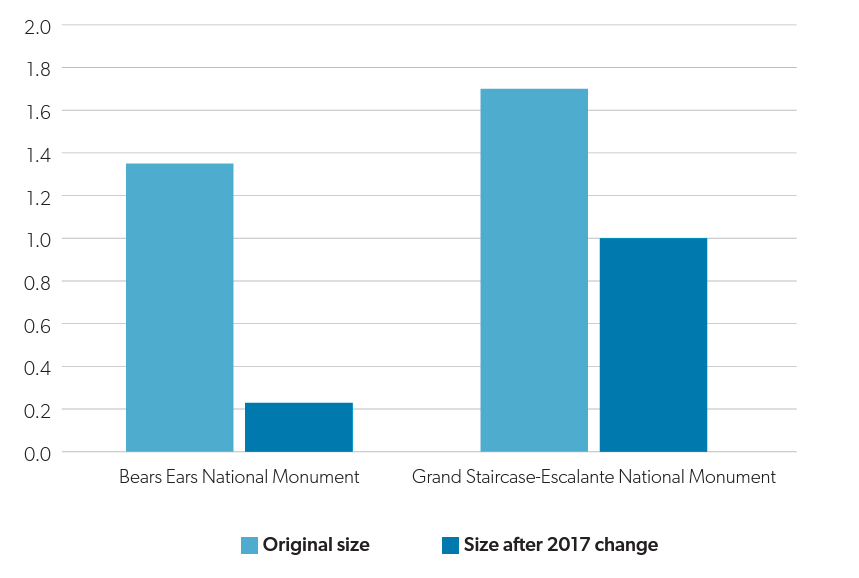

Throughout its history, the Antiquities Act has sparked controversy concerning the scope of executive discretion granted by the legislation. Several recent events have further polarized debate about the act. In December 2016, President Obama created Bears Ears National Monument. Soon after his January 2017 inauguration, President Trump ordered a review of a number of national monuments designated in recent decades.43Kirk Siegler, “With National Monuments under Review, Bears Ears Is Focus of Fierce Debate,” National Public Radio, May 5, 2017; William Yardley, “Trump Signs Order to Reconsider National Monuments Created by Obama, George W. Bush and Clinton,” Los Angeles Times, April 26, 2017; Steinmetz, “Donald Trump’s Move.” The Department of the Interior, the executive agency responsible for overseeing that review, received more than 2.8 million public comments.44“Review of Certain National Monuments Established since 1996; Notice of Opportunity for Public Comment,” US Department of the Interior, 2017, DOI-2017-0002-0001. Following the review process, on December 4, 2017, President Trump issued two proclamations that reduced the sizes of two large national monuments in Utah: Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante.45 Proclamation No. 9681, 82 Fed. Reg. 58081 (December 4, 2017); Proclamation No. 9682, 82 Fed. Reg. 58089 (December 4, 2017). Litigation now underway likely will decide whether the reductions were lawful, but it is unlikely that this litigation will resolve the larger questions about executive discretion under the Antiquities Act.46For example, the Natural Resources Defense Council, The Wilderness Society, and other organizations have filed two court cases, NRDC et al. v. Trump (Bears Ears) and The Wilderness Society et al. v. Trump et al. (Grand Staircase-Escalante). Figure 1 shows the sizes of both monuments before and after their reductions in 2017.

Figure 1. Recent National Monument Reductions (millions of acres)

Source: “Antiquities Act: Maps, Facts, and Figures: Monuments List,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. 2019. https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/monumentslist.htm.

Presidential acts reducing the sizes of national monuments on the basis of the unilateral authority grant- ed to the chief executive by the Antiquities Act are not a new phenomenon. Several past presidents have downsized national monuments, including Presidents Taft, Wilson, Coolidge, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy.47 “Antiquities Act, 1906–2006: Maps, Facts, & Figures,” Monuments List tab, Archaeology Program, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, last updated May 23, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/MonumentsList.htm; John Murdock, “Monumental Power: Can Past Proclamations under the Antiquities Act Be Trumped?,” Review of Law & Politics 22, no. 3 (2018): 349–419. Still, President Trump’s modifications to Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument were the first time that a president had shrunk a national monument in nearly 50 years.48“Antiquities Act, 1906–2006: Maps, Facts, & Figures,” Monuments List tab, Archaeology Program, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, last updated May 23, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/MonumentsList.htm These changes have raised many legal questions about the president’s authority under the Antiquities Act.

The central legal question concerns the president’s authority to designate, reduce the size of, or rescind national monuments, and how far that authority extends. The fundamental question—whether a president can diminish or abolish a national monument unilaterally—has not been adjudicated before, even though the Antiquities Act is more than 100 years old.49Murdock, “Monumental Power.”

Many scholars argue that the president does not have the authority to abolish specific national monuments unilaterally because the law does not explicitly grant revocation powers. Legal scholar and University of Colorado law professor Mark Squillace and his coauthors argue that presidents do not have such authority because Congress did not delegate the power to modify or revoke monument designations.

Hence, those powers are reserved to Congress. The Supreme Court repeatedly has affirmed that any delegation of legislative power must be “construed narrowly to avoid constitutional problems,” meaning that the Antiquities Act’s wording only allows presidents to “reserve” land. Squillace and his coauthors argue that the Antiquities Act’s wording is decidedly different from that of more recent laws that delegate much broader executive authority to designate, repeal, or modify other public land policies.50Mark Squillace et al., “Presidents Lack the Authority to Abolish or Diminish National Monuments,” Virginia Law Review 103 (2017): 55– 71. See also “Letter from Law Professors to Sec’ys Zinke and Ross,” July 6, 2017, http://legal-planet.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/national-monuments-comment-letter-from-law-professors_as-filed.pdf.

Additionally, attorneys at Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer argue that presidents cannot undertake any executive action unless the authority is granted by the US Constitution or by an act of Congress.51Robert Rosenbaum et al., “The President Has No Power Unilaterally to Abolish a National Monument under the Antiquities Act of 1906,” legal memo from Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLC, February 8, 2017, https://naturalresources.house.gov/imo/media/doc/Arnold%20&%20Porter%20Legal%20Memo%20on%20Revocation%20of%20National%20Monuments.pdf. Because no law expressly gives the president the ability to abolish national monuments, such action would be illegal. However, these attorneys also acknowledge that previous presidents have redefined the boundaries or reduced the sizes of national monuments. They argue that the critical factor in determining whether downsizing is legal is whether the change is “so significant that it amount[s] in effect to a revocation of the designation.”52Rosenbaum et al., “President Has No Power.”

Other scholars, such as John Yoo, professor at University of California, Berkeley, and Todd Gaziano, attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation, argue that presidents do have discretionary revocation powers under the Antiquities Act. They argue that traditional principles of constitutional, legislative, and administrative law allow officials with discretionary authority to reverse decisions made by others under the same authority. The courts generally have allowed presidents to modify previous presidents’ decisions when the law grants discretionary power to the sitting president. Yoo and Gaziano argue that no instance exists in American law in which a court has held that a grant of authority does not include the power of the relevant office- holder to revoke prior uses of that authority.53John Yoo and Todd Gaziano, “Presidential Authority to Revoke or Reduce National Monument Designations,” Yale Journal on Regulation 35, no. 2 (2018): 617–65. See also Pennsylvania v. Lynn, 501 F.2d 848, 855–56 (D.C. Cir. 1974).

In 1938, US Attorney General Homer Cummings wrote an opinion concluding that the Antiquities Act grants a president the authority to create national monuments, but not to revoke them.54Proposed Abolishment of Castle Pinckney National Monument, 39 Op. Att’y Gen. 185 (1938). Yoo and Gaziano argue that that opinion and subsequent legal arguments relying on it “make errors of constitutional and statutory interpretation and should not serve as a precedent for future Presidents.”55Yoo and Gaziano, “Presidential Authority.” Additionally, they argue that the Cummings opinion misconstrued a prior opinion.

Disagreement remains about whether and to what extent presidents can modify a previously established monument. Pamela Baldwin, a legislative attorney for the Congressional Research Service, concluded that “a president can modify a previous presidentially-created monument.”56Pamela Baldwin, “Authority of a President to Modify or Eliminate a National Monument,” Congressional Research Service, Rep. No. RS20467 (August 3, 2000). However, the president’s authority to abolish a national monument completely is not explicitly clear because no president has attempted to abolish a previously established national, the Antiquities Act is silent on the matter, and no courts have made a definitive ruling on such an action’s legality.57Alexandra M. Wyatt, “Antiquities Act: Scope of Authority for Modification of National Monuments,” Congressional Research Service, Rep. No. R44687 (November 14, 2016).

It is undeniable that the Antiquities Act gives presidents broad discretion, but scholars continue to debate the legal limits of that discretion. Questions remain about whether a president can abolish an existing national monument, the extent to which a president can expand or reduce existing monuments, and the effective definition of “the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.” Lawsuits currently underway regarding Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments may help clarify such legal ambiguities. However, given that previous court cases have failed to do so, ambiguity likely will persist unless legislative changes are adopted to clearly define the extent of executive discretion under the Antiquities Act.

Policy Recommendations: Clarifying the Limits of Executive Discretion

The Antiquities Act has been instrumental in preserving some of America’s most popular federal lands, but controversy and conflict over its use are likely to continue unless changes are made to the law. The national debate over Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments has presented an opportunity to reevaluate the role of checks and balances in defining executive action under the Antiquities Act. Policy changes that clarify the limits of executive discretion under the act could help reduce uncertainty and controversy surrounding the management of public lands across the United States.

In this section, we explore several potential policy reforms that could help define the extent of executive discretion under the Antiquities Act and create more effective checks and balances. These potential reforms in no way constitute an exhaustive list of positive steps that could be taken to modify the Antiquities Act, but they represent several of the most promising reforms. They include increasing congressional oversight, preventing presidents from reducing or rescinding monuments, and requiring consultation with relevant stakeholders. Such policy changes could be made individually or in combination with one another to help clarify the limits of executive discretion.

Increase Congressional Oversight of Executive Discretion

In an effort to increase congressional oversight of national monument designations, Congress could institute a review process similar to the current approach taken under the Congressional Review Act. Under this act, executive agencies must report the issuance of rules to Congress, and Congress can review those rules. Rules can be overturned if Congress passes a joint resolution of disapproval, which would require the signature of the current president or Congress would have to override the president’s veto.58Valerie C. Brannon and Maeve P. Carey, “The Congressional Review Act: Determining Which ‘Rules’ Must Be Submitted to Congress,” Congressional Research Service, Rep. No. R45248 (March 6, 2019). Congress could use the Congressional Review Act or a similar process to review monument designations made by the president.

Additionally, Congress could set a size limit above which monument designations would require congressional review. The Antiquities Act requires the president to determine “the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected,” but it does not define that term or provide any guidance about the proper sizes of national monuments.5954 U.S.C. § 320301a Congress could provide clarity by requiring the president to consult Congress for designations exceeding a certain size.

Requiring congressional review for monuments over a certain threshold would provide clear limits to the president’s authority to designate areas and would reduce the controversy that often results from larger designations. Because members of Congress are more closely tied to the interests of local constituencies, this reform also would ensure that local stakeholders are involved in decisions that may impact them. Members of Congress would have the opportunity to consult their constituents and bring any concerns to congressional debates before a monument decision is made.

One possible objection to setting a size limit for presidential proclamations is that a size limit may lead to unintended consequences. For example, presidents may choose to designate monuments that are just under the legal limit to avoid congressional review, potentially resulting in monuments that are smaller than what is needed to adequately protect an area. Presidents may also choose to create several adjacent monuments as a way to get around the size limit. Although these outcomes are possible, Congress could still act on its own to preserve any areas that merit protection as national monuments, national parks, or other protected areas. Increasing congressional oversight would provide clarity about the scale and scope of executive discretion in designating national monuments.

Prevent Presidents from Reducing or Rescinding Monuments

Congress could also restrict the president’s ability to reduce the sizes of existing monuments or to rescind them altogether. The Antiquities Act does not provide clear guidance about presidents’ ability to modify national monuments established by their predecessors, but throughout history presidents have changed the boundaries of existing monuments many times.60Carol Hardy Vincent, “National Monuments and the Antiquities Act,” Congressional Research Service, Rep. No. R41330 (November 30, 2018). Congress could provide clarity about the extent of executive discretion under the Antiquities Act by requiring congressional approval in order for a reduction in the size of a monument to take effect or in order for a national monument’s status to be revoked entirely.

Much of the recent controversy over national monuments has revolved around proposals to reduce the sizes of monuments established by previous administrations. If policy reforms were adopted to restrict presidents’ ability to unilaterally redefine the monument designations of their predecessors, uncertainty about the future fate of particular areas would be reduced. Such a policy change could be effectively combined with a policy change placing size limits on new monuments designated on the basis of executive discretion alone. Together, those two changes would help draw clear lines around executive discretion under the Antiquities Act and would prevent abrupt changes in the management of a particular area each time a president with different preferences takes office.

Require Consultation with Stakeholders

Finally, Congress could require consultation with relevant stakeholders and experts before a monument can be designated. The Antiquities Act currently gives the president unilateral authority to designate monuments and does not require any consultation with local leaders or experts.6154 U.S.C. § 320301a Congress could require that before a monument can be designated, the administration must consult with the governor of the state and with the state’s congressional delegation. Congress could also require a public comment period to allow those with relevant knowledge to help inform a potential monument’s designation and management.

Past monument designations have resulted in significant controversy and litigation when presidents designated large monuments without consulting state leaders. For example, in 1996 President Clinton designated the 1.7-million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah without consulting or giving prior notification to Utah’s governor or other state leaders.62Establishing the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: Oversight Hearing before the Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands of the Committee on Resources, House of Representatives, 105th Cong., 1st sess. (August 29, 1997).

Requiring that a president consult with state-level policy makers before a monument is designated in their state would likely increase cooperation and discussion before decisions are made, helping to avoid controversy and litigation afterward. It also would help ensure that local knowledge is considered in the decision-making process. Local leaders often have more information about the lands in their districts and the environmental and economic impacts that a monument designation would have. Including that information in decisions about whether and how to establish a national monument likely would lead to better management outcomes.

Additionally, relevant stakeholders could submit public comments before a monument is established, in a process similar to the notice-and-comment period required for regulations. Congress could amend the Antiquities Act to comport with the modern-day rulemaking process under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Most regulatory changes to public lands must go through the informal rulemaking process, also known as notice-and-comment rulemaking.635 U.S.C. § 551 et seq (2018). Under the APA, any agency or department that pro- poses new rules, rule changes, or new standards must publish those proposals in the Federal Register. The public then has the opportunity to submit comments to the agency or department for 30 to 120 days. Public comments are meant to give policy makers access to knowledge they might not have otherwise had. After the comment period closes, the relevant agency reviews the comments and decides whether to publish a final rule.

Although the APA has existed since 1946, the Antiquities Act has been outside its purview. The APA was originally designed to serve as a check and balance on the discretion of executive agencies in the rulemaking process. In particular, the APA allows federal courts to review and find rules unlawful if the rules are “arbitrary, capricious, [or] an abuse of discretion.”64Todd Garvey, “A Brief Overview of Rulemaking and Judicial Review,” Congressional Research Service,

Rep. No. R41546 (March 27, 2017).

One potential objection to requiring consultation with stakeholders is that it might make the Antiquities Act less effective for conservation. A consultation requirement, however, would not give stakeholders veto power over potential monument designations. Instead, it would allow relevant stakeholders to help inform the president regarding how to best protect an area while also addressing the potential trade-offs of any decision.

Conclusion

Since it was passed in 1906, the Antiquities Act has led to the conservation of many of America’s most iconic locations. It also has resulted in significant controversy when large swaths of land have been designated as national monuments at the sole discretion of the president. Courts have been called upon to determine whether particular designations were appropriate uses of the Antiquities Act, but their decisions have not provided clarity regarding the limits of executive discretion under the law. One key reason for this omission is that when Congress passed the Antiquities Act, it did not provide clear definitions for many of the law’s key terms. Such lack of clarity has led to more than 100 years of uncertainty, controversy, and legal conflict over America’s public lands.

A promising way to make national monument designations less controversial would be to define the extent of executive discretion more clearly. Simple policy changes could clarify the president’s power to designate, reduce the sizes of, and rescind national monuments. Options include increasing congressional oversight, preventing presidents from unilaterally reducing or rescinding existing monuments, and requiring consultation with relevant stakeholders. Such policy changes would likely reduce uncertainty, litigation, and conflict in favor of a more cooperative approach to conserving America’s public lands.