After a lower-than-average snowfall year, Utah Governor Spencer Cox recently declared a state of emergency for Utah due to drought conditions across the state. Living in a desert, residents of Utah may wonder if there’s anything they can do to make a difference. One organization working to help is Utah’s cooperative extension. Utah State University Extension has worked to develop online resources for homeowners, businesses, and farmers with practical tips on how to reduce water usage. They’ve also developed webinars and plan to host workshops that engage the public in the conversation. The Utah State program is just one example of how extension offices at land grant universities across the country are working to translate research into practical knowledge that can be used by everyday people to confront even our most daunting environmental challenges.

Cooperative extension works as a link between universities and communities. This link ensures that university research in fields like agricultural science is shared with communities that can use it to improve on-the-ground land management practices. This Earth Day, policymakers should consider the often-overlooked value that cooperative extension brings to the table as we work to confront our biggest conservation challenges.

The roots of cooperative extension

Cooperative extension first began in the early 1900s with the goal of educating the public about agricultural science and home economics. The Smith-Lever Act provided federally funded grants for land-grant universities to develop cooperative extension programs that educate and work with communities nationwide. The act required additional prorated federal funds be matched by state or private investment.

Since the act was passed, extension initiatives such as 4H have been widely successful and some projects have been increasingly geared towards conservation. Beginning with soil and water conservation in the 1930s, initiatives have broadened to include forestry and at-risk species management— all still relevant for cooperative extension today. Extension projects that focus on conservation have benefited communities and helped address large-scale environmental problems by driving change at the local level.

A valuable tool for engaging landowners

Extension offices create tailored and innovative partnerships and offer many programs to help facilitate this flow of information. For example, a cooperative extension program at the University of Illinois focuses on improving stormwater management through educating homeowners on drainage issues and how to reduce run-off from individual lots.

Other cooperative extension initiatives have been successful at helping to solve more complex issues like wildlife protection. A cooperative extension project at Cornell University works with Putnam County, NY and helps protect Indiana Brown Bat populations. The project helps communities build bat houses and aids residents in bat-proofing their homes to ensure baby bats will not be trapped inside during hot, summer months.

Engaging landowners is crucial to achieving environmental improvements, especially in the realm of wildlife conservation. Most endangered species rely on private land for their habitat, and landowners often know the most about the local conditions on their land. University extension is unique in its ability to involve local landowners in conservation and provide them with a resource they can trust. Surveys of landowners suggest they are more willing to work with extension officials than other groups like state and federal governments or non-profits. This higher level of trust may be because extension officials are local people who live and work in the same communities as landowners. Extension is also focused on education, while government officials are typically responsible for enforcing regulatory requirements that might restrict what landowners can do on their property.

Engaging the public in conservation

Conservation projects led by extension offices are diverse and happening all across the United States, from public classes about soil and water conservation to projects enlisting the help of volunteers to identify and preserve the largest trees in Idaho. This diversity is made possible because each extension office has the flexibility to address the needs of its community and local environment.

For example, cooperative extension initiatives at Mississippi State University focus on coastline restoration. One of their ongoing projects involves cleaning up abandoned crab traps that create navigational and environmental hazards in the Mississippi Sound. The program offers a financial reward to shrimpers who collect these lost traps and bring them to a disposal location. Another extension project at the University of Georgia utilizes volunteer work, organizing ongoing event cleanups with hundreds of participants who help to clean the shorelines of Camden County. These river cleanups have collected over 4,300 pounds of litter since they began in 2014.

Other cooperative extension initiatives focus on forestry. A cooperative extension program at Clemson University, for example, identified hazards to shrinking longleaf pine forests in South Carolina. These forests support a rich plant community but have been reduced to just 3% of their native range due to increased urbanization and fire prevention that has hampered seed germination. Clemson’s extension program developed workshops for small forest owners, showing them how conservation could be achieved at a lower cost. Workshops provided demonstrations on longleaf pine restoration, prescribed fires, and bottomland hardwood management. The extension project also produced a financial analysis of the cost-effectiveness of these techniques.

Follow-up surveys showed that nearly 90% of participants rated the workshops as “good” or “excellent” and 86% indicated they would change their forest management practices as a result. The extension project is part of ongoing forestry initiatives in South Carolina that have helped to protect over 94,000 acres of land critical to forest, plant, and wildlife diversity. The program works as a useful template for other initiatives, showing what can be accomplished when university researchers are able to identify a problem and solution and then encourage the community to work together.

Conserving iconic species of the American West

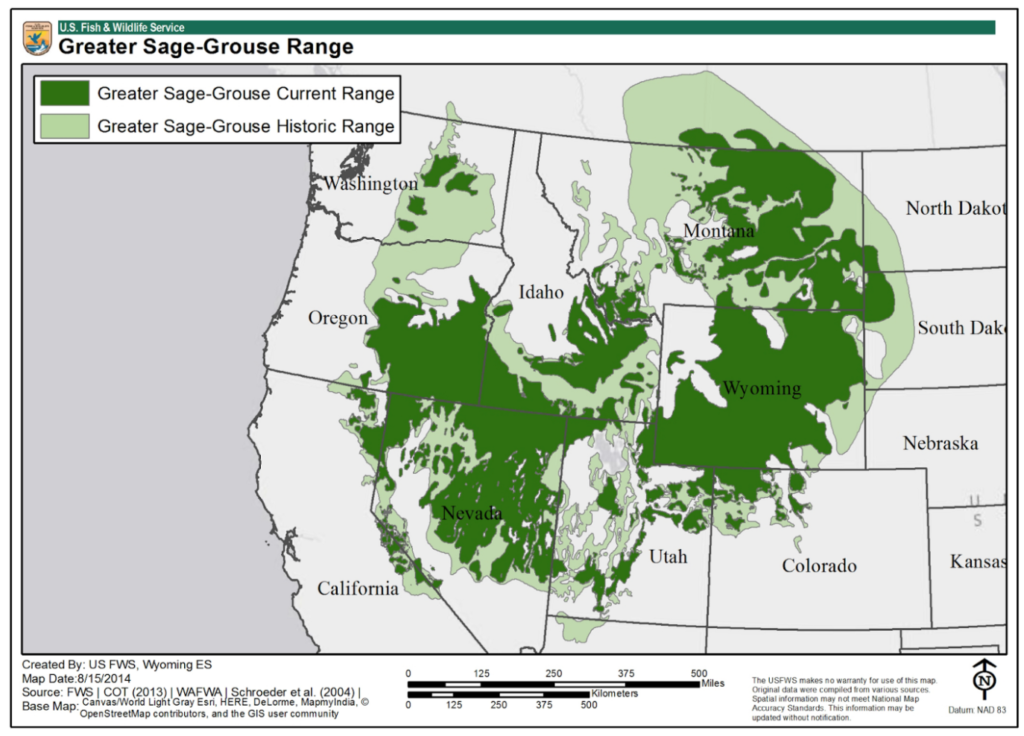

In addition to forestry and water conservation, cooperative extension programs have been successful as part of larger, landscape-scale initiatives focused on wildlife conservation. Efforts led by Utah State University’s cooperative extension program were especially helpful in protecting the greater sage-grouse. The bird is the largest grouse species in North America and relies on sage brush for food and nesting. Once found across many western states, biologists now estimate that the greater sage-grouse occupies only 41% of its historic range. Loss of essential sagebrush due to development has been the main cause of the species’ decline.

Current vs. historical range of the Greater Sage-Grouse

Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

In response to the bird’s decline, in 2010 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) determined that the greater sage-grouse was a “candidate species” for full listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Political leaders in states with greater sage-grouse populations worried that an ESA listing would negatively affect productive land use and leave protective efforts in the hands of federal bureaus that lacked local knowledge. Western states began developing and implementing individualized greater sage-grouse management plans.

As part of its management plan, the state of Utah utilized cooperative extension as an important tool in greater sage-grouse conservation. The Utah Community-Based Conservation Program (CBCP), an extension project run by Utah State University, began working with stakeholders in 1996 to organize community-based working groups focused on greater sage-grouse recovery in Utah. These working groups are composed of local landowners and government entities and provide valuable information concerning migration routes and seasonal range for the bird. After the ESA announcement in 2010, the CBCP utilized information garnered from these local working groups to complete an assessment that outlined plans for vegetation management, invasive species prevention, and fire control.

To help implement these conservation plans, the CBCP partnered with the Utah Governor’s Office, local government, private landowners, and wildlife managers. Building these partnerships allowed the CBCP to boost information flow and stimulate involvement. The CBCP continues to publish peer-reviewed research on sage-grouse conservation and has developed a manual to help local landowners better understand how to conserve sage-grouse on their land.

Efforts from the CBCP and other initiatives paid off. Utah’s greater sage-grouse population grew by 40% between 2013–2014. In addition to population increases, over 249,000 acres of greater sage-grouse habitat were enhanced and restored. In 2015 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that the greater sage-grouse no longer warranted protection under the ESA and cited state and local efforts as the main catalysts for the changed listing. Although there has been some disagreement concerning population growth in Utah since 2015, the FWS has stood by their 2015 ruling and the greater sage-grouse remains an important feature of Utah’s biodiversity. The successful conservation of greater sage-grouse in Utah is an important example of how coordinated efforts that allow for local landowners’ involvement can achieve impactful results.

Cooperative extension for a better environmental future

Extension programs have unique attributes that make them well suited for conservation initiatives. Relying on a pattern of teaching, researching, and providing public service allows cooperative extension to offer research-based and localized solutions to landowners who are crucial conservation partners. These private landowners are more likely to participate in conservation if they have the opportunity to partner with a group they can trust and are familiar with. Landowners can find this trust and familiarity in partnering with cooperative extension programs.

It’s tempting to meet our biggest environmental challenges with equally big solutions that often come from the top down and are elegantly crafted to fit every situation. But meeting our most daunting environmental challenges will require more tailored solutions that consider the unique circumstances of time and place. Working from the ground up can help ensure that local people are involved in crafting solutions that truly work. Cooperative extension may be one of our most powerful and most overlooked tools for working toward better environmental outcomes.