1. Introduction

Beginning in World War II, the United States and Mexico struck an agreement called the Bracero program, where Mexican workers could temporarily relocate to the United States to aid with agricultural labor shortages. During the 1960s, the Bracero program abruptly ended. Suddenly, abundant foreign labor disappeared, and farmers turned to machines to keep production going.1San (2023) Many economic models assume that innovation grows with higher populations, but terminating the Bracero program was a striking counterexample. Still, many of the most tech-forward companies in the United States were founded by immigrants, especially those in Silicon Valley.2Saxenian (2000) With evidence suggesting both positive and negative correlations between immigration and technology, it’s critical to figure out exactly what their relationship is. Without a clear picture of how these interact, well-intentioned policy could harm the future of US tech development.

To assist policymakers in knowing how best to act, this piece seeks to answer the question, “How do immigration and technological innovation affect one another?” This is done by thoroughly reviewing existing research and drawing conclusions and policymaking strategies from the lessons learned. By better understanding this relationship, the United States can move forward confidently in achieving long-term economic growth.

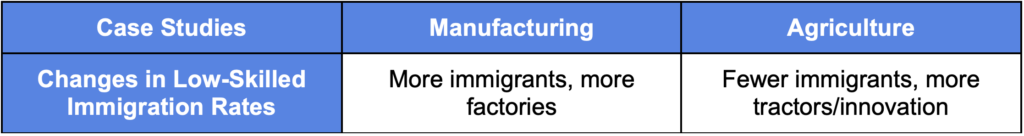

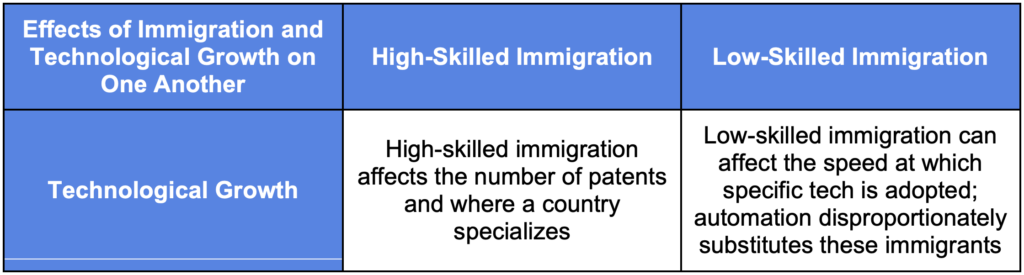

Research shows that the pattern between immigration and tech growth is more nuanced than a positive or negative correlation statement. They can be complements and substitutes depending on the field and the skill level. For high-skilled work, immigration and technology enjoy a complementary relationship; as high-skilled immigration increases, so does the quantity of patenting. High-skilled immigrants also bring benefits to their professional peers, further encouraging innovation. For low-skill jobs, technology and labor complement or displace each other, and while this kind of substitution may affect high-skilled immigrants, it also disproportionately affects low-skilled immigrants. Because research often refers to immigrants with at least a bachelor’s degree as “high skill” and those with less education as “low skill,” this paper will do likewise. Gaining more education can help one become more “skilled,” but that is beyond the scope of this paper. This piece is structured to highlight how the relationship between immigration and tech changes based on skill level. Sections 2 and 3 examines the relationship between both high-skill and low-skill immigration and technological growth, while Section 3 discusses current policies and proposes strategies based on the literature.

2. The Relationship between Immigration and Technological Growth

Research shows that high-skilled immigrants complement technology development in several ways. These include specialization, patenting booms, spillover effects, and employment opportunities, each explored in more detail in this section. When educated scientists and engineers move to the United States, they bring their specialized expertise. Without roots in their new country, they can move from city to city, bringing booms in patenting rates. Additionally, their presence and mentorship can spur others to further innovation. The following studies each provide evidence of immigrants’ effect on technological growth and support one another in their findings.

Specialization

In their 2020 study, Bahar et al. found that immigrants increased patents in their home country’s specialty. For example, if Taiwan specializes in semiconductors, a Taiwanese scientist immigrating to the United States will help increase semiconductor patents. The authors found that doubling the number of inventors increases the likelihood of a country specializing in the same type of technology as the inventors’ home by 50 to 60 percent. Additionally, doubling the number of inventors correlates with higher annual patenting rates by 29 to 43 percent. This is significant evidence that migrant inventors spread ideas and knowledge across borders, strengthening the argument that high-skilled immigrants complement tech development with their specialized knowledge and mobility.3Bahar, Choudhury, and Rapoport (2020)

Booms and Breakthroughs

High-skilled immigrants help provide patenting booms in areas experiencing breakthroughs. Studying the Immigration Act of 1990, Kerr (2010) found that mobile immigrants contribute to such booms. Before this act, US immigration policy imposed strict quotas on how many workers could enter the country at a time. The Immigration Act raised quotas and “dramatically released pent-up immigration demand from [scientists and engineers] in constrained countries.”4Kerr (2010) These immigrants were finally allowed to enter the country and move to the development hotspots in their respective fields, propelling invention and innovation. Kerr filtered out any noise that could skew his results by only considering the top 1 percent of the most cited patents as breakthroughs and requiring a city to have at least 10 of these high-quality patents to be considered a breakthrough site. Through carefully filtered data, he concluded that high-skilled immigrants bolster invention.

Spillover Effects and Employment

High-skilled immigrants contribute to technological development not only through knowledge sharing and their own patenting efforts but also by encouraging their peers to innovate. Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010), like Kerr, used patenting data to show that areas with more immigrant scientists experienced higher per capita patent rates. The authors wrote that “even immigrants who do not patent themselves may increase patenting by providing complementary skills to inventors, such as entrepreneurship.” While much growth comes directly from the actions of high-skilled immigrants, the literature finds that their presence in an area can catalyze invention.

Another notable effect of high-skilled immigration is evident in journal publications. Stuen et al. (2023) found that foreign-born students were more likely to pursue and earn higher degrees in science and engineering (S&E), outnumbering native students. As a result, these foreign-born students had a more significant impact on publication numbers in S&E journals, contributing to a higher volume of research output. Stuen et al. argued that this increased impact was due to the higher number of international students, a finding that aligns with Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle’s research, which also underscored the significance of immigrant numbers.5Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010)

High-skilled immigrants also bring positive employment effects in tech. In her study of Silicon Valley, Saxenian (2000) illustrated how various policy changes affected the region. Loosening immigrant restrictions always resulted in labor force booms, primarily from Taiwanese, Chinese, and Indian scientists. When these immigrants faced challenges to their career development, they networked with one another, building up new businesses.6Kerr (2010) As Saxenian learned from Silicon Valley, some of the most tech-forward enterprises in the nation were founded by Chinese or Indian immigrants.7Saxenian (2000)

High-Skill Takeaway

Together, these studies show that high-skilled immigrants complement tech growth. Bahar et al. found that immigrants are crucial to spreading specialized knowledge across borders,8Bahar, Choudhury, and Rapoport (2020) while Kerr found that mobile immigrants can sustain breakthroughs.9Kerr (2010) Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle concluded that immigrant scientists and engineers promote higher patents per capita.10Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) Stuen et al. showed that international students publish in S&E journals at a higher rate,11Stuen, Mobarak, and Maskus (2023) and Saxenian’s case study showed when the United States allowed more high-skilled immigrants to enter the country, innovation and entrepreneurship increased, with benefits still felt today.12Saxenian (2000)

As technology is an ever-expanding sector, specialized knowledge brought by mobile immigrants helps accelerate the process. In Saxenian’s words, “not only are skilled immigrants highly mobile, but the technology industries in which they are concentrated are the largest and fastest-growing exporters and leading contributors to the nation’s economic growth.”13Saxenian (2000) Thus, when expert immigrants relocate to areas where they can add the most value, they promote innovation breakthroughs. Due to the complementarity between high-skilled workers and tech growth, rates for both can grow.14Lewis (2013) Supporting this, Kerr provided a graph showing how the share of immigrant patents has grown since 1975, as depicted in Figure 1. The clear upward trend shows that immigrant inventors have increasingly contributed to innovation.

Figure 1

The main takeaway is that people propel growth, and their ideas advance what is possible. By collecting the best minds (natives and immigrants), the United States can more effectively boost technology growth and thereby improve the quality of life for all within its borders.15Brunello, Garibaldi, and Wasmer (2007) High-skilled immigration is an invaluable tool for long-term economic growth due to its strong, positive effect on technological development. However, while high-skilled immigrants influence tech development, low-skilled immigrants also play a crucial role.

3. Low-Skilled Immigrants and Technological Growth

Similarly to high-skilled immigrants, research finds that low-skilled and technology can still complement each other. This is consistent with economic theory, which predicts that labor becomes more productive with the right tools. Interestingly, research has found that low-skilled immigration can even accelerate the pace at which certain technologies are spread. However, compared to their high-skilled counterparts, low-skilled immigrants face a greater risk of being replaced by technology. The following case studies will show how both complementarity and substitution very depending on the sector.

Accelerating Tech Adoption

Take the Age of Mass Migration as an example. Between 1820 and 1920, the United States experienced an immigration boom, which brought a surge of low-skilled workers. Kim (2007) found that this influx of low-skilled immigrants helped manufacturing technologies spread nationwide. Factories, able to break down complex tasks into simple, specialized actions, could readily fill their vacancies with the newly arrived immigrants. This spurred factory growth and helped spread manufacturing across the country.16Kim (2007) However, with the passage of the 1921 Emergency Quota Act, immigration was curtailed and factory growth slowed.17Kim (2007) This scenario illustrates the complementarity between improved immigration rates and the spread of tech (specifically the factory model,). As one increased, so did the other; similarly, when one was halted, the other decreased.

Substitution Creeps In

The spread of the factory model during the Age of Mass Migration provides compelling evidence that immigration and technology still complement each other, even when the immigrant is high or low skilled. However, low-skilled immigrants face a threat that high-skilled labor often does not: displacement by machines. Therefore, it is insufficient to simply state that low-skilled immigration speeds up tech use. More accurately, changes in low-skilled immigration rates affect technology use differently depending on the sector.

One study on automation (Lew and Cater 2018) found that restricting immigration in the agricultural sector led to more tractor use. Lew and Cater conducted a convenient natural experiment in the Northern Great Plains region in the early 1900s, where conditions on both sides of the US-Canada border were nearly identical. In the 1920s, the United States and Canada diverged in their immigration policies, and from then on, the United States adopted more tractors while Canada hired more immigrant workers.18Lew and Cater (2018) The substitution away from scarce immigrant labor in the United States led to the faster proliferation of the tractor than if immigration rates had remained unchanged. Another great case study was the end of the Bracero program in the 1960s. San (2023) studied the effects of ending the program and found that “the Bracero exclusion induced a sharp increase in innovation in technologies related to crops with a higher share of Bracero workers relative to crops with a lower share.” When immigrant labor was suddenly unavailable, farmers were forced to innovate new tech to keep up production. The jump in innovation is seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2

San quickly pointed out that technology is only sometimes an adequate substitute. He stated that even with their new technology, farmers’ profits suffered in the long run without immigrants and all the benefits they bring to an economy.19San (2023)

When examining the effect of robot implementation on jobs, Javed (2023) found that “robot adoption leads to differential job losses for immigrants in the United States , and the employment effect for immigrants is approximately 1.76 times that observed for natives . . . the burden of robot adoption falls disproportionately on recent immigrants and foreign-born men and women.” Through his analysis, Javed concluded that automation also affects different workers depending on their skill level. He argued that low-skilled workers are met with displacement, while high-skilled workers enjoy productivity boosts and invent better technology.

Regarding tech-skill substitution, Lant Pritchett believes that entrepreneurs can fill specific niches with immigrant labor instead of spending resources to innovate a redundant solution.20Kurtz-Phelan (2023) By meeting specific needs with people instead of automation, the United States can refocus its best minds to tackle issues that can’t be solved with abundant human labor. For example, self-driving cars could be replaced with hired drivers. Meanwhile, innovators could focus their expertise on more complex issues. Pritchett argues that substitution and opportunity cost can be used to stack the United States’s deck for long-term growth.

Low-Skill Takeaway

Like their higher-skilled counterparts, low-skilled immigrants can enjoy boosted productivity through using technology and even accelerate the pace at which certain technology spreads. However, unlike their higher-skilled peers, low-skilled immigrants also have a substitutionary relationship with technology. The main takeaway from the literature is that changes in low-skilled immigration rates affect technology usage differently depending on the sector.

4. Policymaking Strategies

Expand Options for Permanent and Temporary Immigration

Currently, the United States is facing a shortage of workers that can be filled with both natives and immigrants. Workers of all skill levels have a role in influencing the country’s technological progress. High-skilled immigrants can share their expert knowledge, increase patent supply in S&E, and catalyze innovation among their native peers.21Bahar, Choudhury, and Rapoport (2020),22Kerr (2010),23Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) Meanwhile, low-skilled immigrants can accelerate the use of specific technologies and fill abundant job vacancies, allowing entrepreneurs to use their time and resources to make worthwhile developments instead of redundant tech.24Kim (2007),25Center for International Development (2016)

Improving options for temporary worker visas would be a big step forward. Some foreign-born workers only want to stay temporarily. These individuals represent a demographic eager to contribute to US-based jobs, potentially offering significant gains for the country’s GDP.26Saxenian (2000) However, by restricting temporary worker programs, the United States misses out on these potential benefits these workers would otherwise bring to the economy.27Kurtz-Phelan (2023) Without opportunities here, these would-be contributors are likely to take their gains elsewhere. By loosening restrictions on temporary workers and permanent immigrants of all skill levels, the US can capture these unrealized gains and innovations to stack its deck for long-term economic growth.

Another approach to increasing the stock of high-skilled STEM workers is to use subsidies to incentivize natives to specialize in technology fields. While improving education and training for US-born scientists is critical for the country’s long-term growth, relying solely on subsidies risks sacrificing the long-run benefits for short-term gains. Subsidies would fill tech positions with people who may have a lower comparative advantage than experienced immigrants.28Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) In Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle’s words, “the additional natives drawn into science and engineering might have lower inventive ability than the excluded immigrants, and such natives might have contributed more to the US economy outside science and engineering.”29Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) By using subsidies to restrict high-skilled immigrants from entering the workforce, the United States would miss out on the benefits previously described. A better approach would be to improve education while also hiring high-skilled immigrants, thus attracting and producing the best and brightest talents.

Promote Optional Practical Training and the H-1B Visa

One attractive option for prospective workers is Optional Practical Training (OPT). While the H-1B visa is already a known, longer-term option for immigrants who want to stay and work in the United States, it is a lottery, making it difficult for an individual to secure their visa. Instead, OPT lets nonimmigrants remain and work in the United States for a time after completing a degree and allows a buffer (up to three years) for workers trying to get H-1B status. Khoo (2023) reports that “international students do value work experience in the United States and make their schooling decisions on that dimension. Policies that restrict their ability to gain work experience will adversely affect their higher education enrollment in the US.” OPT is an effective tool to boost international student enrollment and graduation in STEM fields, from bachelor’s degrees to doctorates.

As for the H-1B, raising the visa limit would allow more experts to contribute to the economy. This includes increasing the productivity of high-tech firms and helping younger firms bring in the talent they need to survive and compete against older firms.30Mandelman, Mehra, and Shen (2024) Improving the availability of both the OPT and H-1B programs is a worthwhile change. In a 2010 study, Kerr and Lincoln found that higher H-1B admissions were met with more immigrants working in S&E fields. Additionally, patenting by foreign-born inventors increased. The resulting uptick in immigrant patenting showed high demand for US jobs blocked by restrictive H-1B caps. The authors stated that “total invention increased with higher admissions primarily through the direct contributions of immigrant inventors,” and “immigrant scientists and engineers are central to U.S. technology formation and commercialization.”31Kerr and Lincoln (2010) The greater the number of immigrant inventors allowed into US jobs, the larger their contribution to the tech industry.

Attract Experts to Advance the CHIPS Act

As Saxenian (2000) found, Taiwanese inventors were among the largest contributors to the success of Silicon Valley. Additionally, Bahar et al. (2020) found that bringing in experts helped boost patenting in their specialized fields. Pursuing the options described above is in the United States’s best interest if it wants to leverage the CHIPS Act to ensure semiconductor self-reliance. By attracting Taiwanese experts and improving pathways for them to enter the workforce, the United States can set itself up for rapid growth in the semiconductor industry. Again, highly skilled immigrants (and temporary workers) bring direct contributions and spillover effects that propel innovation even further.32Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010)

Policy Takeaway

While improving domestic STEM personnel is a worthwhile goal, training and employing new scientists and engineers takes time. In the meantime, the best way to catalyze invention and drive long-term tech growth in the United States is to bring in high-skilled immigrants from abroad. Given that there is a scarce supply of experts in certain technologies (like semiconductors), reducing their barriers to entering the country is crucial. The experts will bring valuable knowledge and all the beneficial spillover effects of high-skilled immigration. The United States should look to the global talent pool to permanently or temporarily fill its shortage of scientists and engineers.

5. Conclusion

Immigration and technological growth affect each other in significant and nuanced ways. High-skilled immigrant scientists and engineers are poised to launch innovation forward, while low-skilled immigrant workers are ready to fill market niches, thus redirecting invention efforts toward other endeavors that can’t be solved simply with more human labor.33Center for International Development (2016) Furthermore, low-skilled immigration can also speed up the adoption of new, worthwhile innovations. Policymakers interested in promoting long-run economic growth and prosperity, particularly through initiatives like the CHIPS Act, should use the effects of immigration on technology as vital tools.

I recommend increasing accessibility to permanent programs like the H-1B visa and expanding temporary work programs like OPT. These changes would allow the best minds to bring their expertise and entrepreneurship, benefiting long-term tech growth and catalyzing immediate growth in S&E fields. Allowing permanent or temporary low-skilled immigration is also important. These workers influence the rate at which technology is adopted, and their presence can help redirect high-skilled inventors toward efforts beyond automation. Policymakers should focus on expanding these programs to capture the most value possible.

References

Bahar, Dany, Prithwiraj Choudhury, and Hillel Rapoport. “Migrant Inventors and the Technological Advantage of Nations.” Research Policy 49, no. 9 (2020): 103947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.103947.

Brunello, Giorgia, Pietro Garibaldi, and Etienne Wasmer. “Higher Education, Innovation and Growth.” In Education and Training in Europe, edited by Giorgio Brunello, Pietro Garibaldi, and Etienne Wasmer. Oxford University Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199210978.003.0004.

Center for International Development. “Lant Pritchett: Labor Mobility Barriers Distort Technological Innovation.” YouTube video, May 9, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqyXIe5up68.

Hunt, Jennifer, and Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle. “How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation?” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2, no. 2 (2010): 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.2.2.31.

Javed, Mohsin. “Robots, Natives and Immigrants in US Local Labor Markets.” Labour Economics 85 (2023): 102456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2023.102456.

Kerr, William R. “Breakthrough Inventions and Migrating Clusters of Innovation.” Journal of Urban Economics 67, no. 1 (2010): 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.006.

Kerr, William R., and William F. Lincoln. “The Supply Side of Innovation: H‐1B Visa Reforms and US Ethnic Invention.” Journal of Labor Economics 28, no. 3 (2010): 473–508. https://doi.org/10.1086/651934.

Khoo, Pauline. “If You Extend It, They Will Come: The Effects of the STEM OPT Extension.” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, December 5, 2023. https://www.thecgo.org/research/if-you-extend-it-they-will-come-the-effects-of-the-stem-opt-extension/.

Kim, Sukkoo. “Immigration, Industrial Revolution and Urban Growth in the United States, 1820-1920: Factor Endowments, Technology and Geography.” NBER Working Paper #12900, February 2007. https://doi.org/10.3386/w12900.

Kurtz-Phelan, Dan. “Immigration before Automation: A Conversation with Lant Pritchett.” Foreign Affairs Interview (podcast), April 20, 2023. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/podcasts/immigration-before-automation-lant-pritchett.

Lew, Byron, and Bruce Cater. “Farm Mechanization on an Otherwise ‘Featureless’ Plain: Tractors on the Northern Great Plains and Immigration Policy of the 1920s.” Cliometrica 12, no. 2 (2018): 181–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-016-0157-2.

Lewis, Ethan. “Immigration and Production Technology.” Annual Review of Economics 5, no. 1 (2013): 165–191. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080612-134132.

Mandelman, Federico, Mishita Mehra, and Hewei Shen. “Skilled Immigration Frictions as a Barrier for Young Firms.” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, January 25, 2024. https://www.thecgo.org/research/skilled-immigration-frictions-as-a-barrier-for-young-firms/.

San, Shmuel. “Labor Supply and Directed Technical Change: Evidence from the Termination of the Bracero Program in 1964.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 15, no. 1 (2023): 136–163. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20200664.

Saxenian, AnnaLee. “Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs.” University of California, Santa Cruz Working Paper #15, May 2000.

Stuen, Eric T., Ahmed M. Mobarak, and Keith Maskus. “Skilled Immigration and Innovation: Evidence from Enrollment Fluctuations in US Doctoral Programs.” The Economic Journal 122, no. 565 (2023): 1143–1176.