Introduction

As in many states, Utah is currently in a discussion about modifying its tax system to minimize its economic costs while still raising a roughly equal amount of tax revenue—a so-called revenue-neutral policy change. One way of accomplishing that goal is by expanding the sales tax base and using the additional revenue to reduce the sales tax rate (or lower other tax rates or eliminate harmful taxes).

But what is the right sales tax base? Economists have studied the issue closely and agree on several basic principles. Above all, economists argue that a sales tax should cover all final consumption, including both goods and services, unless good reasons exist to exempt individual goods or services.1 David Brunori, 2016, State Tax Policy: A Primer (Fourth Edition), Rowan and Littlefield, page 64; John Mikesell, 1998, “The Future of American Sales and Use Taxation,” in The Future of State Taxation, edited by David Brunori, Urban Institute Press. Common motivations for exemptions that we discuss include the potential for consumption taxes to fall most heavily on low-income people (called a regressive tax), when goods are business inputs, and Utah’s near total exemption of services from taxation.

Tax policy researchers across the political spectrum agree that narrow, targeted policies (such as tax credits) are usually a better way to address the regressive nature of the tax than blanket exemptions.2 Aidan Davis, “Options for a Less Regressive Sales Tax in 2018,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), 2018, https://itep.org/options-for-a-lessregressive-sales-tax-in-2018/; Nicole Kaeding, “Sales Tax Base Broadening: Right-Sizing a State Sales Tax,” Tax Foundation, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/sales-tax-base-broadening/. Current policies exempting services and partially exempting groceries are unlikely to effectively minimize the tax burden on Utah’s consumers. More targeted policies combined with a broad tax base and low tax rates may achieve the same levels of public revenue at a much lower fiscal and economic cost.

Tax a Broad Base at Low Rates

The amount of tax revenue collected from a sales tax is a simple product of two factors: the tax rate and the tax base (what is taxed). In the absence of tax avoidance or evasion, a state could cut the tax rate in half, while doubling the size of the base (or vice versa), and revenue would stay about the same. A 1% tax on $100 billion tax base is the revenue equivalent of a 2% tax on a $50 billion tax base: both raise $1 billion in tax revenue.

Public finance economists argue that taxing a broader base at a lower rate minimizes the economic costs of taxation.3 David Hyman, 2014, Public Finance: A Contemporary Application of Theory to Policy (Eleventh Edition), Cengage Learning, pages 407-408. Taxes generate what economists call a “deadweight loss” or “excess burden.” Those terms refer to costs to the economy above and beyond the value of the revenue collected. These costs include less economic activity due to more unrealized gains from trade, and more tax evasion because of the “wedge” taxes insert between the prices paid by consumers and the prices received by sellers. Deadweight losses represent the amounts by which the costs of taxation on buyers and sellers exceed tax revenues. Hence, all else equal, economists prefer tax rates to be lower because deadweight losses are minimized.4 Jonathan Gruber, 2007, Public Finance and Public Policy (Second Edition), Worth Publishers, page 582-583. And deadweight losses are not just greater at higher rates, they increase quadratically. In other words, a 2% tax rate has four times the deadweight loss of a 1% sales tax.5Hyman, ibid. 408-409

The more goods and services that are exempted from the sales tax base, the higher we would expect the sales tax rate to be in order to produce the same level of public revenue. Academic research suggests that every new exemption added to the sales tax base increases the tax rate by 0.1 to 0.25 percentage points to maintain revenue neutrality.6 Andreea Militaru and Thomas Stratmann, 2014, A Survey of Sales Tax Exemptions in the States: Understanding Sales Taxes and Sales Tax Exemptions, Mercatus Working Paper, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/survey-salestax-exemptions-states-understanding-sales-taxes-and-sales-tax-exemptions That conclusion is driven by two related factors. First, as states exempt more consumption items from their tax bases, the rate needs to be increased in order to generate the same amount of revenue. Second, an increasing rate creates stronger incentives for industries to lobby for exemptions specific to the things they sell. That process can feed on itself, as more exemptions lead to higher rates, which leads to more lobbying and more exemptions, which means that rates must increase again to raise the same amount of revenue.

A broad tax base also provides for a more stable tax source over time. Revenue that fluctuates from year to year can make government budgeting challenging. Even if the same amount of revenue is raised on average per year, effective government budgeting is much easier if it comes from a stable revenue source. The issue of stability may lead states to prefer property tax and broad sales taxes over income taxes, which fluctuate more with the business cycle (especially corporate income taxes).

Evaluating Exemptions and Alternatives

Exemptions should be treated with caution if the aim is to implement a tax system characterized by minimal economic costs. Importantly, policymakers must remember that granting exemptions means that the still-taxed goods and services must now be taxed at a higher rate to maintain the same level of public revenue, thereby raising the economic cost of taxation. A 2017 joint report from the Utah State Tax Commission and the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst found that Utah exempts at least 89 specific goods from the sales tax base. However, over half of them (48) are exemptions for business inputs.7– Utah State Tax Commission and the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst, Utah State Tax Commission, 2017, https://tax.utah.gov/esu/misc/exemptionstudy-2017-11.pdf. For the remaining non-business exemptions, a few are necessary to comply with federal law, such as exempting purchases made with food stamps. These exemptions range from large revenue losses for prescription drugs (over $154 million) to small ones such as food purchases less than $1 in vending machines ($85,000 revenue loss).

Each exemption is a policy choice that policymakers should scrutinize carefully. We examine three areas of Utah’s tax exemptions in detail: business inputs, services, and necessities like groceries.

Exemptions for Business Inputs Prevent Tax Pyramiding

A common exemption granted is to business inputs and business-to-business sales. Some difficulties can arise when a good or service is purchased by both businesses and consumers, but ways already exist for addressing that issue, such as tax-exempt certificates or credits for taxes paid. Taking steps to exempt such transactions follows directly from the basic principle of tax policy that sales taxes should apply only to final (retail) sales. Taxing business purchases creates pyramiding in the tax system, which means that industries are effectively taxed at different rates depending on how many stages of production and resale they have.8– Robert Cline, John Mikesell, Tom Neubig, and Andrew Phillips, 2005, “A Survey of Sales Tax Exemptions in the States: Understanding Sales Taxes and Sales Tax Exemptions,” Council on State Taxation, page 1-2, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/standcomm/sccomfc/Business-Inputs-Study.pdf.

Economic analysis of tax incidence shows that impacts rarely fall where intended. Regardless of the stage of production at which taxes are collected and remitted to the fiscal authority, the tax burden gets shifted forward and backward depending on the relative elasticities of demand and supply at each stage of the supply chain.9 Hyman, Public Finance, 2014. For example, if it is easy for consumers to shift their spending away from spending on a certain good (what economists call “elastic demand”), then producers will bear most of the burden of that tax, regardless of who the law says must pay the tax.

Consider a hypothetical company making chocolate. It purchases cocoa powder from a supplier and is untaxed on that purchase. After making the chocolate, however, the chocolatiers collect and remit the sales tax to the state government. If a sales tax was collected at both points of sale (the purchase of the cocoa powder and the final sale of the chocolate) then the effective tax rate on the final chocolates would be higher than that of the cocoa powder sales. Such differential taxation rates distort consumer choices and, if other states have lower tax rates, would put in-state businesses at a disadvantage.10 Robert Cline, John Mikesell, Tom Neubig, and Andrew Phillips, A Survey of Sales Tax Exemptions in the States: Understanding Sales Taxes and Sales Tax Exemptions, Council on State Taxation, 2005, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/standcomm/sccomfc/Business-Inputs-Study.pdf, page 1-2.

Tax policy should avoid giving differential advantages to certain businesses over others. In the case of taxing business inputs or business-to-business sales, the tax advantage is granted based on a company’s relatively early position in a supply chain and not in service of a public-minded end.

Exemptions for Services Raise Rates on Taxed Goods and Distort Consumer Choice

Utah, like many states, generally applies its sales tax to purchases of “tangible personal property,” or what are commonly referred to as “goods.” But, in general, Utah does not tax services.

Economists have long criticized the distinction between goods and services for the purpose of taxation. Both goods and services provide value to consumers. Excluding services leads to perverse outcomes and shrinks the tax base (which entails higher tax rates on consumer goods to maintain the same level of public revenue).11 Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute, “A Visual Guide to Tax Modernization in Utah Part One: Sales and Use Taxes,” 2018, https://gardner.utah.edu/wp-content/uploads/Nov2018-TaxBooklet-Final.pdf. For example, when a consumer purchases a lawn mower to mow their own lawn, they will pay sales tax. But if they hire a lawn care specialist, the service will not be taxable. Both of these activities accomplish the same goal and involve exchanging money for value. Yet only one activity currently is taxed.

The lawn care example illustrates another important aspect of exempting services: it means that low-income households pay a larger share of their income in taxes than high-income households. Sales taxes are regressive overall, which means that they disproportionately fall on low-income individuals.12Research generally agrees that the sales tax is moderately regressive, though this depends on assumptions about the incidence of the tax, i.e., whether the buyer or the seller bears the burden, which is harder to measure since it will not be the same for every good (see Joseph A. Pechman, Who Paid the Taxes, 1966-85?, Brookings Institution Press). However, research that looks at lifetime incidence, rather than annual incidence, finds that regressivity may be overstated by looking at any one year (Don Fullerton and Gilbert E. Metcalf, “Tax Incidence,” in Handbook of Public Economics, Volume 4, edited by Alan J. Auerbach and Martin Feldstein, 2002). But lower income households spend little of their income on services, while high income households spend a larger share.13 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 1110. Deciles of income before taxes: Annual expenditure means, shares, standard errors, and coefficients of variation, Consumer Expenditure Survey,” 2017, https://www.bls.gov/cex/2017/combined/decile.pdf. Including services in the sales tax base will make the tax code less regressive. Thus, expanding the sales tax base has broad support across the political spectrum of tax policy experts: it simultaneously makes a tax code more efficient (if rates are lowered) and less regressive.14 Michael Mazerov, 2009, Expanding Sales Taxation and Services: Options and Issues, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/expanding-sales-taxation-of-services-optionsand-issues; Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2016, Why Sales Taxes Should Apply to Services, https://itep.org/why-sales-taxes-should-apply-toservices/; Kaeding, Sales Tax Base Broadening, 20172018.

In a survey of states from the Federation of Tax Administrators of 142 services categories that could be purchased by consumers (excluding business services), Utah taxes 58 of them, or 40.8% of services. This number does put Utah above the average of 35.9% across the 50 states and DC, but there are also 18 states (and DC) that tax more services than Utah does.15 Federation of Tax Administrators, “Sales Taxation of Services,” 2017, https://www.taxadmin.org/sales-taxation-of-services. Washington, Hawaii, New Mexico, South Dakota, and Delaware all tax at least 118 services (again excluding business services)—more than double the number Utah taxes.16Delaware and Washington tax many of these services through their gross receipts tax, rather than the sales tax (Delaware has no sales tax). To take one example, very few states tax barbershops and beauty parlors, but six states do: this same group of five plus Iowa. The FTA also reports that since their last survey in 2007, three states have significantly increased the number of services that they tax, and that two of those—North Carolina and DC—did so as part of an overall package to lower tax rates (in their cases lowering income taxes).17 The third, Connecticut, expanded to more services while also increasing their sales tax rate, in an attempt to raise more revenue. See: https://www.taxadmin.org/btn-0817_services.

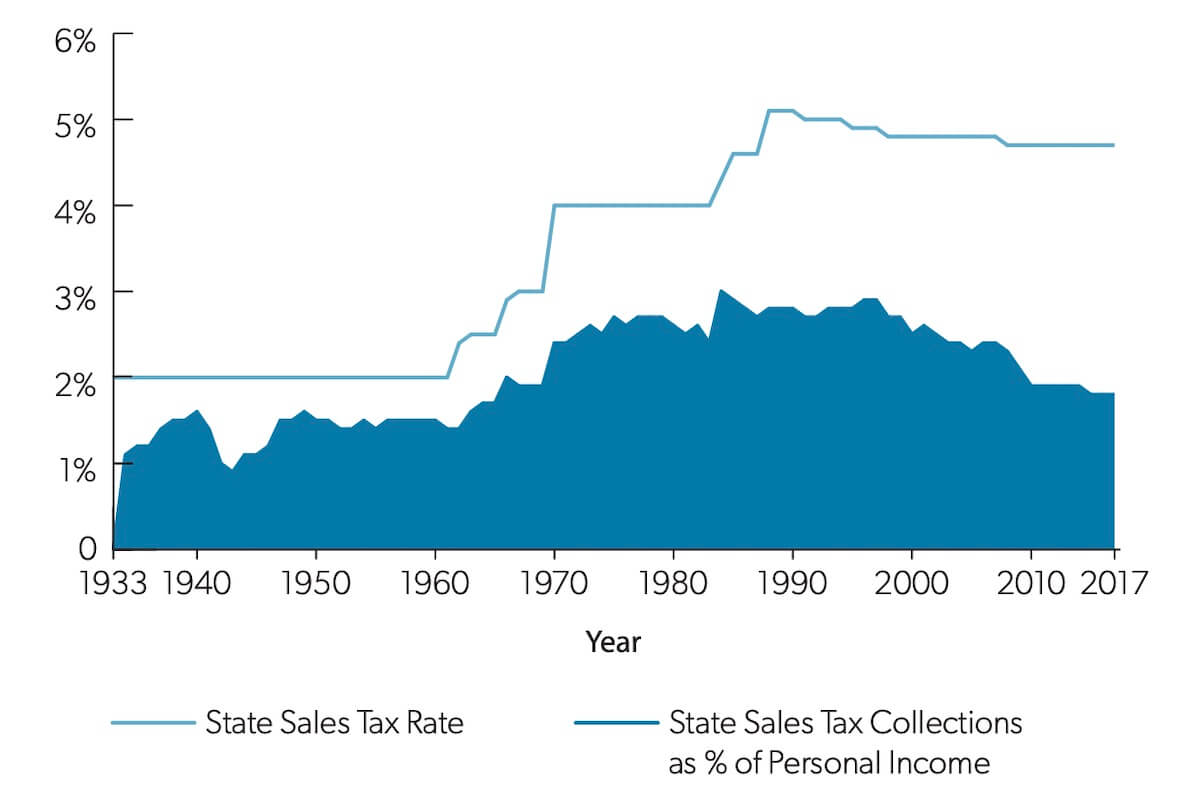

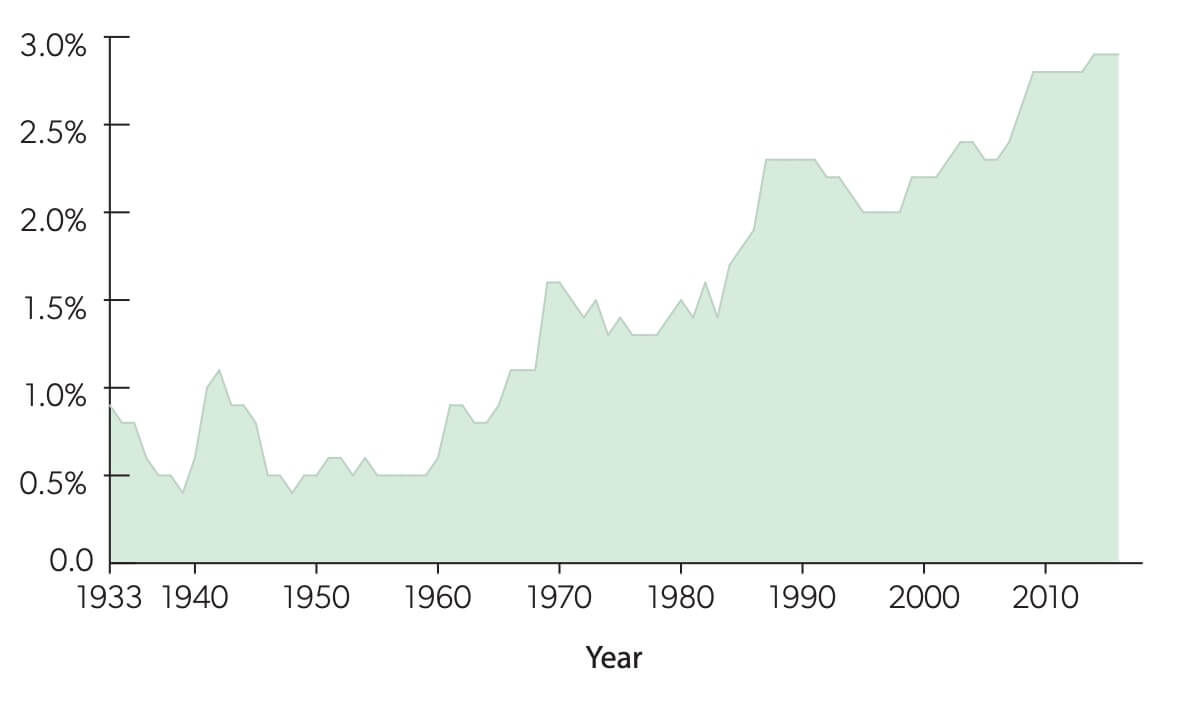

The importance of removing exemptions for services also is clear from the increasing share of consumer spending on services relative to goods. In 1933, consumers spent slightly more on goods than on services, with services accounting for about 48% of spending. In 2017, more than two-thirds of consumer spending (68%) was on services.18The Utah Foundation, “The Everyday Tax: Sales Taxation in Utah,” 2018, http://www.utahfoundation.org/uploads/rr754.pdf. Data for Utah do not go back as far, but current consumption spending numbers are similar to the United States as a whole: in 2017, 65.8% of Utahns’ spending was on services.19Bureau of Economic Analysis. SAEXP1 Total personal consumption expenditures (PCE) by state. 2019. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=30&isuri=1&year_end=-1&classification=naics&state=0&yearbegin=-1&unit_of_measure=levels&major_area=0&area=49000&year=-1&tableid=524&category=6524&area_type=0&statistic=-1&selected_income_data=0. Figure 1 shows the trend in sales tax rates and collections. The gap between them illustrates that, even as the sales tax has risen, the tax revenues have stayed roughly the same and even started to decline.

Shown another way, Utah’s gap between its sales tax rate and its collections is growing. Even though the sales tax rate is 4.7%, sales tax collections make up a little less than 2% of personal income. And this gap has been growing over time. While we would never expect the gap to be zero (e.g., because households save some of their income), a growing gap is a clear indication of the sales tax base eroding.

Figure 1: Consumption Expenditures on Goods and Services in Utah

Note: Personal income data are from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and tax rate data are from the Utah State Tax Commission. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, GDP and Personal Income, 2019, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&isuri=1&acrdn=6; Utah State Tax Commission, History of the Utah Tax Structure, 2019, https://tax.utah.gov/econstats/history.

Figure 2: Gap Between Tax Rate and Actual Sales Tax Collections in Utah

Source: Utah State Tax Commission, History of the Utah Tax Structure, 2019, https://tax.utah.gov/econstats/history.

There are some possible downsides or limitations to taxing services, and part of the historical reluctance of states to tax services is related to these issues. First, the paperwork burden on service providers may be greater than for those selling goods that will raise the costs of doing business. For example, businesses are already keeping track of inventories of goods, but there is not a similar process in place for tracking services. Second, many service providers are small operations, providing limited personal services such as mowing lawns or shoveling snow. Compliance costs may be especially high for these smaller businesses.20 – Mazerov, Expanding Sales Taxation and Services, 2009. In the service sector, 82.9% of businesses in Utah have nine or fewer employees compared with 65.6% in the retail trade sector.21 Census Bureau, County Business Patterns, 2016. The retail trade sector is NAICS 44-45 and services is NAICS code 81. See: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/tables.2016.html But as mentioned above, there are a handful of states that tax services widely, and Utah can learn about the potential costs by looking at the experience of these states.

Finally, the main justification for a broad sales tax base is to limit the ability of consumers to substitute untaxed goods for taxed ones and so create a stable source of government revenue. Importantly, this raises revenues in a way that does not discriminate against consumers with different preferences. A legitimate concern is that broadening the sales tax base could be an attempt to increase total revenue, rather than to accomplish genuine tax reform. Any tax rate changes or elimination of exemptions should be tied to an overall revenue neutral proposal.

Exempting Necessities Like Groceries to Avoid Regressive Effects is Less Efficient than Targeted Policies

Most states exempt the purchase of groceries from the sales tax, at least partially, or provide a credit to citizens to offset taxes paid on groceries. Only three states tax groceries at the full sales tax rate and provide no offsetting credit.22 Eric Figueroa and Samantha Waxman, “Which States Tax the Sale of Food for Home Consumption in 2017?,” March 1, 2017, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/whichstates-tax-the-sale-of-food-for-home-consumption-in-2017. Utah is no exception to this general trend, taxing groceries at a reduced rate (1.75%), but still applying local sales taxes to groceries.23The Utah Foundation, 2018. Utah generally defines groceries as food that is not prepared by the seller.24The Utah State Tax Commission has an online matrix to assist in determining what is and is not “food” for the purposes of this tax exemption: https://tax.utah.gov/sales/food-rate So food bought at restaurants is not taxed at a lower rate, but food purchased to be prepared at home is.

Why exempt groceries? Two related arguments usually are made. First, food is a necessity, and taxing the basic necessities of life should be avoided when possible. Second, exempting food makes the sales tax less regressive. Poorer households spend a disproportionate share of their income on groceries, so the exemption makes the tax code less burdensome on them. But for both of those reasons, partially exempting all groceries is an ineffective instrument for achieving this goal. Groceries also make up a large part of the potential tax base: in 2017, US grocery purchases represented about 20% of total consumer spending on goods and about 6% of all spending.25Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Income and Product Accounts, Table 2.4.5. Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product,” 2019.

While some food can be considered a necessity, not all food covered by the grocery exemption fits the definition. Luxury food items, such as filet mignon and caviar, are exempted to the same extent as necessities. One option for more targeted exemptions is limiting it to Utah’s WIC program list.26 Utah WIC Program, “Authorized WIC Foods,” 2018, https://demosite.utah.gov/wic/wp-content/uploads/sites/30/2018/08/WIC-Authorized-Food-Art18-Online.pdf Cash registers could be programmed to recognize those items, just as they are programmed to recognize items covered by the federal SNAP (food stamps) program. Grocers might even set aside a few aisles of the store as “tax exempt” aisles to assist customers with making choices. No state has tried a program exactly like this, but Utah could be a pioneer.

The primary drawback to limiting exemptions is that it is only slightly more targeted than current policy and so its effectiveness may be limited. Furthermore, purchases of food with SNAP (food stamps) already are exempt from the sales tax, and many low-income households make most of their grocery purchases using SNAP.

Alternative Policies

The Earned Income Tax Credit or a Grocery Tax Credit Can Limit Regressivity

Two other options could be used to provide more targeted relief: a state Earned Income Tax Credit or a grocery tax credit.

While the federal Earned Income Tax Credit has been around since 1975, in recent years many states have adopted versions of the EITC, often claimed as a simple percentage of the federal credit. The EITC is available to low- and middle-income working families, with much smaller benefits to households without children. The credit phases in at a certain income level (about $15,000 for households with two or more children), then phases out gradually after about $49,000. Because families with two or more children still receive a small credit even if they earn more than $50,000 in income, it also benefits middle-class families.27 Internal Revenue Services, “Do I Quality for EITC?,” 2019, https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/do-i-qualify-forearned-income-tax-credit-eitc

In addition to individuals not working, seniors and young adults under 25 do not qualify for the credit, so the EITC may represent only a partial solution to the regressive effects of taxing groceries. It does, however, have a budgetary impact: a refundable credit at 10% of the federal EITC level would cost around $45 million in Utah.28Erica Williams and Samantha Waxman, “How Much Would a State Earned Income Tax Credit Cost in Fiscal Year 2019?,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/howmuch-would-a-state-earned-income-tax-credit-cost-in-fiscal-year But that revenue loss is much smaller than the reduced sales tax rate on groceries overall which is around $200 million.29There were $6.77 billion in grocery sales in Utah in 2017. If these were taxed at Utah’s full 4.7% tax rate rather than the current 1.75%, it would generate about $200 million in revenue. See: https://tax.utah.gov/econstats/sales/yearly-grocery In other words, for less than one-quarter of the grocery exemption, Utah could institute an EITC with $155 million left over to lower tax rates.

Another option to address the regressive nature of taxing food purchases is a grocery tax credit. Currently, only four states (neighboring Idaho, as well as Hawaii, Kansas, and Oklahoma) have adopted such a credit. Each state’s credit works a little differently, but they can be targeted even more accurately than an EITC.30 Eric Figueroa and Samantha Waxman, “Which States Tax the Sale of Food for Home Consumption in 2017?,” 2017, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/which-states-tax-thesale-of-food-for-home-consumption-in-2017 It could reach seniors and those not working as well, for example. No state requires any recordkeeping in order to qualify for the credit. Instead, the four states tax groceries at their full tax rates and then issue a credit through a taxpayer’s income tax return.31Katherine Loughead, 2018, “Sales Taxes on Soda, Candy, and Other Groceries,” Tax Foundation, https://taxfoundation.org/sales-taxes-on-sodacandy-and-other-groceries-2018/.

These grocery credits are calculated on a per-person basis, usually with different credits for low- versus middle- income households. Idaho takes the unique step of excluding low-income households, based on the logic that they are likely to use SNAP, which already is tax exempt.32South Dakota also used to offer a credit to offset food taxes, but dropped it in recent years. South Dakota has no income tax to help administer this credit, so anyone qualifying for the credit needed to fill out a specific tax form, and the utilization rate was fairly low. On these credits generally see: https://www.cbpp.org/research/idaho-is-the-only-state-to-exclude-low-income-familiesfrom-its-grocery-tax-credit. The budgetary cost will depend on exactly how such a credit is structured and who qualifies, but estimates could be made by looking at the four other states where a grocery tax credit is in place.

Each of these three alternatives is more targeted than current policies that tax groceries at a lower rate or entirely exempt groceries and other necessities. This minimizes the deadweight losses associated with the taxes. Still, the policies have their limitations. Utah, and other states, can limit the economic costs of taxation and resolve concerns about regressive effects by pursuing any of these options over exemptions or partial exemptions.

Conclusion

Tax Policy Should Avoid Exemptions and Favor Broad Bases Taxed at Low Rates

Utah is in a position to make its overall tax system more efficient without reducing state spending and state services. There are a number of ways to expand the sales tax base: including services, removing goods from Utah’s list of 48 exemptions, and taxing groceries at the full sales tax rate. Utah can use the additional revenue from expanding the sales tax base to lower tax rates overall while maintaining the same level of revenue. Whether to lower sales or income tax rates is an important question to discuss, but lowering both rates is a potential compromise.

The fundamental finding from research on taxation is that policy should avoid exemptions and favor low tax rates levied on broad tax bases. Each exemption means that taxed goods and services must be taxed at higher rates to produce the same level of public revenue. A good use of the revenue from ending exemptions is to lower income tax rates, rather than sales tax rates, as taxing income imposes a greater burden on the economy. Efforts to alleviate the regressive effects of taxing necessities may be concentrated more effectively on tax credits or lowering other taxes like the income tax than on making special exemptions. For example, improved tax credit programs such as an EITC for low-income individuals and families can be used to offset changes that adversely impact them (e.g., if groceries were taxed at the full rate).