Introduction

The Risk of negative Post-COVID-19 Attitudes on Immigration

The Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US has been pervasive and extreme. It has caused a death toll higher than 100,000 (as of May 27, 2020) and it has ushered an economic contraction with the unemployment rate at 15% nationally (as of April 2020) and a decline of US Gross Domestic Product by 4.8% just in the first quarter of 2020. Families have been left struggling and in economic hardships. The mental, human, and social consequences of the lock-down and of social isolation have been deep. Many small businesses have been struggling to survive. Entire communities have been brought to the verge of collapse by a healthcare crisis that has overextended hospitals and exhausted health care workers.

Besides these material changes, the pandemic has also brought insidious changes in people’s attitudes. The fear of a virus originated from abroad, namely from China, has increased the hostility towards Chinese, Chinese-Americans, and immigrants in general.1 Paula Larsson, “Anti-Asian racism during coronavirus: How the language of disease produces hate and violence,” The Conversation, March 31, 2020, https://theconversation.com/anti-asian-racism-during-coronavirus-how-the-language-of-disease-produces-hate-and-violence-134496” Moreover, in times of crisis and economic uncertainty, the temptation to find scapegoats is very high. Immigrants have typically been targeted in such times, as a group that is easy to identify and to blame.2 Neeraj Kaushal, Blaming Immigrants: Nationalism and the Economics of Global Movement (Columbia University Press, 2019).

Fueling these feelings, on April 22, President Donald J Trump announced in a tweet an “Executive Order to temporarily suspend immigration into the United States!” to protect “the jobs of our GREAT American Citizens.” On April 24, he signed an executive order, which, albeit with many qualifications, halted for two months the issuing of residence permits (green cards) to people who wanted to immigrate to the US. While this measure in the short-run will not affect too many people (as very few are attempting to move to the US in time of pandemics), it is damaging as it strengthens the insidious and incorrect sentiment that immigrants are hurting the US economy and US workers. It also reveals that the current administration is using the pandemic to carry even further their restrictive immigration agenda. Other immigration restrictions may be on the way.

The most recent executive order is in line with several actions of the current administration aimed at reducing, slowing and making harder legal immigration, while at the same time doubling down on enforcement and deporting undocumented immigrants. Previous executive orders banned immigration from some countries, deemed at risk of terrorism, affecting mostly highly educated and students from those areas. The number of F1 student visas issued has been declining in each of the last three years.3Elizabeth Redden, “International Student Numbers in U.S. Decline,” Inside Higher Ed, April 23, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2019/04/23/international-student-numbers-us-decline. There has been no policy or action to relax the very strict limit on skilled-immigrants visas (H1-B) in spite of the large demand for them exceeding the quota each year since 2014.4Youyou Zhou, “Winning the H-1B visa Lottery is no Longer Enough.” Quartz, May 13, 2019, https://qz.com/1614743/winning-the-h-1b-visa-lottery-is-getting-more-and-more-difficult/.

What is most discouraging of these policies is that the President regularly claims their rationale to be a benefit for US workers and for the US economy. In what follows, I will argue that such a vision is based on an erroneous understanding of the working of the US economy. In place of closing, America, I will propose how and why more open immigration policies should be an essential part of the economic recovery during the reopening.

The fallacy of restricting immigration

Both before and after the COVID crisis, the economic reasoning used to justify immigration restrictions has been that halting immigration would help Americans get jobs. Let me state in very simple terms that such a view is not founded in economic analysis or economic evidence. In fact, it denotes a lack of familiarity with the economic analysis of immigration. The idea is based on an oversimplification that obscures understanding of the actual economic effects of immigrants.

Within a very simple model of demand and supply of homogenous workers in one local labor market, with all other things fixed and when immigrants supply only labor, an inflow of immigrants would reduce wages or displace some of the existing workers. No reasonable economist, however, would think that such a simplistic model, used simply to illustrate a potential competition effect, is a good representation of what happens to a complex economy like the US, when a differentiated group of individuals, like immigrants, joins it.

First, immigrants are not only workers but also consumers. Immigrants demand goods and services, increasing the demand for additional workers.5Giovanni Peri, Derek Rury, and Justin C. Wiltshire, “The Economic Impact of Migrants from Hurricane Maria,” IZA Discussion Papers 13049, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13049/the-economic-impact-of-migrants-from-hurricane-maria.Second, immigrants are also entrepreneurs, at a higher rate than natives, and as such, they create new firms and produce new jobs.6Robert W. Fairlie, and Magnus Lofstrom, “Immigration and Entrepreneurship,” In Handbook of the Economics of International Migration 1, 877-911, (North-Holland, 2015), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2597992. Third, they are a highly differentiated group, with innovators, scientists among them who help firms’ productivity stimulating job creation, and also manual workers, who specialize in jobs that US citizens are moving out of.7Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber, “STEM workers, H-1B visas, and productivity in US cities,” Journal of Labor Economics 33, no. 1 (2015): S225-S255; Giovanni Peri, “The Effect of Immigrants on U.S. Employment and Productivity,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/el2010-26.pdf. The US should definitely encourage some of these individuals, who stimulate the US economy and complement US workers’ abilities, to come to the US during the recovery after the COVID-19 crisis and help create a virtuous economic cycle.

Moreover, there is abundant evidence that many parts of the economy promptly respond to the inflow of immigrants magnifying their positive effect. Firms invest more to take advantage of new workers, and they adjust and improve technology.8William W. Olney, “Immigration and firm expansion,” Journal of Regional Science 53, no. 1 (2013): 142-157, https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12004. Trade is stimulated by the international links brought by immigrants.9Giovanni Peri and Francisco Requena‐Silvente, “The trade creation effect of immigrants: evidence from the remarkable case of Spain.” Canadian Journal of Economics 43, no. 4 (2010): 1433-1459, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40925283. All these factors contribute to grow the economy and to add jobs, and they have been shown to be quantitatively important by extensive economics research in the last 15 years. 10Giovanni Peri, “Should The US Expand Immigration?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 39, no. 1, (2020), https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22185. In aggregate, immigration does not hurt the employment and wages of natives, as these mechanisms completely reverse the pure competition effect described in the simple model.11Giovanni Peri, “Should The US Expand Immigration?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 39, no. 1, (2020), https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22185.Giovanni Peri, “Immigrants, productivity, and labor markets,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no. 4 (2016): 3-30.

The massive current unemployment rate of Americans is generated by a drop in demand for labor due to the fact that people and businesses are limited in their interactions, and uncertainty about reopening is huge. As a consequence of this, immigration has also come to a standstill. However, when businesses open their doors, the role of immigrants, as entrepreneurs, innovators, scientists, consumers, and workers, will help American workers to get back on track. Immigrants will again contribute to the growth of the US economy.

Recognizing the economic relevance of immigrants and promoting growth

An additional reason for implementing policies reversing the decline in immigration, which has happened for the last decade in the US, is the recognition, brought by COVID-19 of the essential role of immigrants during the crisis.12Giovanni Peri, “20 Years of Declining Immigration and the Disappearance of Low Skilled Immigrants,” UC Davis Global Migration Center, 2019, https://globalmigration.ucdavis.edu/20-years-declining-immigration-and-disappearance-low-skilled-immigrants. In the US as a whole, as well as in the largest and most affected states (California and, even more, New York and New Jersey), immigrants were significantly over-represented among four groups of workers that were considered “essential” during the pandemics and continued to work.

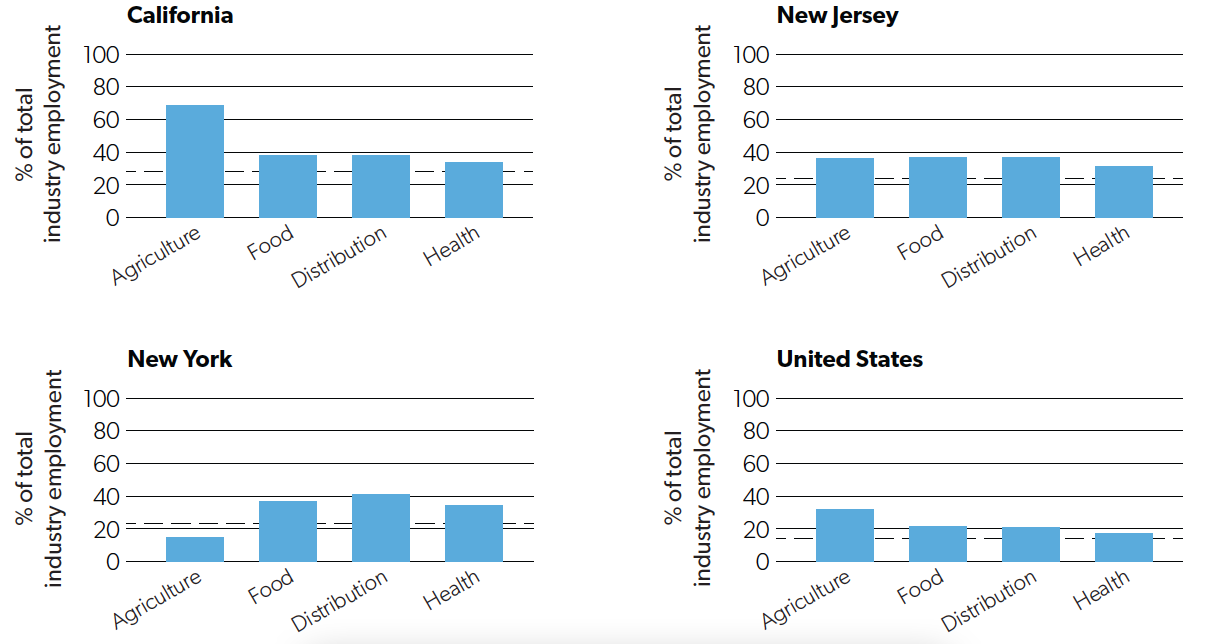

Considering the four sectors of “Agriculture”, “Food processing”, “Distribution”, and “Health Care” as “essential”, Figure 1 shows the share of foreign-born workers.13For details on the sector definitions, see: Giovanni Peri and Justin C. Wiltshire, “The Role of Immigrants as Essential Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” UC Davis Global Migration Center, 2020. https://globalmigration.ucdavis.edu/role-immigrants-essential-workers-during-covid-19-pandemic. In all but the agricultural sector in New York, each is above the dashed line that represents the share of immigrants in the population of that jurisdiction. Focusing on health workers—many of whom were essential and at-risk workers during this pandemic—and looking at the most affected states of New York and New Jersey, where these workers were exposed to the most extreme risk, we see that close to one-third of them are foreign-born. While foreign-born workers constitute only 14% of the overall population in the US, they comprise about 35% of health workers in New York and 31% in New Jersey.

Turning to agriculture, the US national production of agricultural goods depends heavily on foreign-born workers, which represent one-third of national workers, and close to 70% of California’s agricultural workers. Overall, it is indisputable that immigrants are a large and over-represented proportion of the group of essential workers in the US. They keep stores stocked with food first from farms, then to grocery stores, and ultimately to our kitchen tables.

Figure 1. Percentage of Immigrants in Essential Industries14Source: Author’s calculations using American Community Survey Data, 2018.

Hence, in the light of their important role during the pandemic and their potential role in stimulating growth at the reopening of the economy, it would be wise to consider policies that open rather than close our immigration system. It will not be easy to attract immigrants to the US after this health crisis. Certainly, it will take an inversion of current policy. Some simple policy suggestions are the following:

- Simplifying access to permanent residence for foreign-born health care workers who have been working during the pandemics.

- Consider the possibility of converting temporary visas into permanent residence or allow a path to legalization for workers who were in essential sectors and worked during the pandemic.

- Expand the H1B skilled visa program, which helps create high tech jobs, which in turn have strong positive effects on local economies.

- Facilitate the enrollment of international students and increase the number of F1 visas to reduce and reverse their steep decline.

Conclusion

Immigration has been declining in the US for the past 20 years.15Peri, “20 Years of Declining Immigration.” In part, this was because of the large decline in immigration from Mexico as well as the effects of restrictive and obsolete immigration policies. During the last four years, this restrictive tendency has accelerated, and immigration has declined even further. COVID-19 risks are generating fear and uncertainty, which may trigger further aversion to immigration and even more restrictive policies. As scholars, we need to make sure that solid economic research, rather than prejudice and a caricature of economic analysis, is part of the considerations in deciding immigration policies for the growth of the US economy during the transition out of the crisis.

References

1. Paula Larsson, “Anti-Asian racism during coronavirus: How the language of disease produces hate and violence,” The Conversation, March 31, 2020, https://theconversation.com/anti-asian-racism-during-coronavirus-how-the-language-of-disease-produces-hate-and-violence-134496.

2. Neeraj Kaushal, Blaming Immigrants: Nationalism and the Economics of Global Movement (Columbia University Press, 2019).

3. Elizabeth Redden, “International Student Numbers in U.S. Decline,” Inside Higher Ed, April 23, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2019/04/23/international-student-numbers-us-decline.

4. Youyou Zhou, “Winning the H-1B visa Lottery is no Longer Enough.” Quartz, May 13, 2019, https://qz.com/1614743/winning-the-h-1b-visa-lottery-is-getting-more-and-more-difficult/.

5. Giovanni Peri, Derek Rury, and Justin C. Wiltshire, “The Economic Impact of Migrants from Hurricane Maria,” IZA Discussion Papers 13049, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13049/the-economic-impact-of-migrants-from-hurricane-maria.

6. Robert W. Fairlie, and Magnus Lofstrom, “Immigration and Entrepreneurship,” In Handbook of the Economics of International Migration 1, 877-911, (North-Holland, 2015), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2597992.

7. Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber, “STEM workers, H-1B visas, and productivity in US cities,” Journal of Labor Economics 33, no. 1 (2015): S225-S255; Giovanni Peri, “The Effect of Immigrants on U.S. Employment and Productivity,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/el2010-26.pdf.

8. William W. Olney, “Immigration and firm expansion,” Journal of Regional Science 53, no. 1 (2013): 142-157, https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12004.

9. Giovanni Peri and Francisco Requena‐Silvente, “The trade creation effect of immigrants: evidence from the remarkable case of Spain.” Canadian Journal of Economics 43, no. 4 (2010): 1433-1459, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40925283.

10. Giovanni Peri, “Should The US Expand Immigration?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 39, no. 1, (2020), https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22185.

11. Giovanni Peri, “Do immigrant workers depress the wages of native workers?” IZA World of Labor (2014), https://wol.iza.org/articles/do-immigrant-workers-depress-the-wages-of-native-workers/long.; Giovanni Peri, “Immigrants, productivity, and labor markets,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no. 4 (2016): 3-30.

12. Giovanni Peri, “20 Years of Declining Immigration and the Disappearance of Low Skilled Immigrants,” UC Davis Global Migration Center, 2019, https://globalmigration.ucdavis.edu/20-years-declining-immigration-and-disappearance-low-skilled-immigrants.

13. For details on the sector definitions, see: Giovanni Peri and Justin C. Wiltshire, “The Role of Immigrants as Essential Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” UC Davis Global Migration Center, 2020. https://globalmigration.ucdavis.edu/role-immigrants-essential-workers-during-covid-19-pandemic.

14. Source: Author’s calculations using American Community Survey Data, 2018.

15. Peri, “20 Years of Declining Immigration.”