The battle over how gig economy workers should be classified continues to rage on in California. Last month California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill that exempts more workers from the requirements of AB5 — a controversial law that went into effect at the beginning of this year that makes it more difficult for companies to classify workers as independent contractors. And next month, voters will decide whether to approve Proposition 22, which would override AB-5 by categorizing app-based drivers as independent contractors.

AB5 created a 3-part test for determining whether a worker should be classified as an independent contractor or an employee. In effect, it made it much more difficult to legally classify workers as independent contractors and impacted wide swaths of the California economy. After concerns that workers who had traditionally worked with many different clients would not be able to perform their work at all, policymakers acted to exempt a long list of occupations (including youth sports coaching, interpreting services, consulting, photography, videography, appraisers, home inspectors, landscape architects, competition judges, underwriters, auditors, and risk management) from AB5’s requirements.

The controversy surrounding AB5 illustrates that sorting workers into two neat categories (as employees or independent contractors) is a difficult task. The American workplace is a dynamic place. Workers and employers are constantly coming up with new and innovative arrangements for how they will work together. Instead of continuing to sort workers into two boxes, employment law needs to evolve to allow for continued innovation along with financial security for workers in more flexible arrangements. The most promising way to do that would be to structure benefits so that they’re attached to the worker instead of the job. Employment law should give workers and businesses more than just two options for structuring their working lives.

Flexibility and stability in the gig economy

Even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers were concerned about the financial well-being of workers in the gig economy. Drivers for ride-sharing services like Uber and food delivery services like Doordash are generally categorized as independent workers who set their own hours and decide how much they want to work each week. They can also work for multiple platforms to bring in additional income. But on the flip side of this flexibility and autonomy are worries about financial security. Companies that employ independent workers don’t have to provide sick leave, paid time off, or retirement income — benefits typically provided to full-time W-2 employees.

Worries about the welfare of gig economy workers like Uber and Lyft drivers have been amplified since the onset of the economic downturn spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the transportation sector, in particular, drivers were left with massive reductions in demand for rides and much lower monthly incomes. A survey of gig workers released in May found that over half of respondents had lost 75–100 percent of their income. The survey also found that 21 percent had no health insurance, and 45 percent were not prepared to handle a $400 emergency expense.

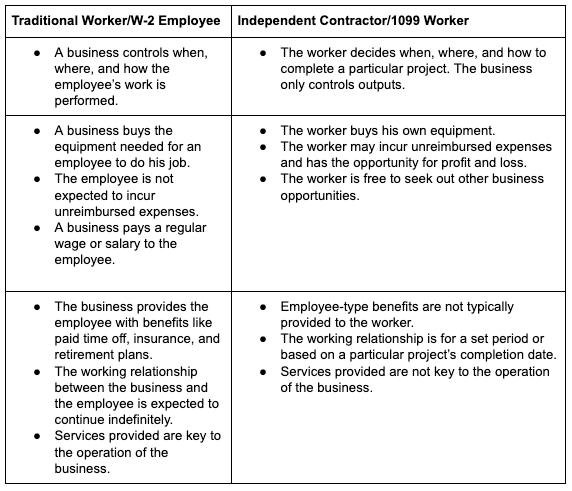

The IRS provides guidance on whether a worker should be categorized as a traditional W-2 employee or an independent contractor. That guidance is reflected in Table 1 below. Key criteria include whether a worker can set their own hours and whether they can work for multiple clients at once, in addition to questions about benefits. This criterion illustrates the tradeoffs between flexibility and autonomy on the one hand and financial stability on the other that workers must navigate.

Table 1: Determining a worker’s employment status

Source: Internal Revenue Service

California’s approach may be too rigid

To address concerns about the stability of gig economy workers, California lawmakers passed AB5 in 2019, establishing a 3-part test for determining whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor. The law, which went into effect at the beginning of 2020, was intended to protect workers from potential exploitation by employers who might otherwise classify workers as contractors to avoid having to provide benefits. The 3-part test made it much more difficult to categorize a worker as an independent contractor in the hopes that companies would have to provide more benefits and financial perks to keep workers afloat.

The 3-part test established by AB5 states that a worker is only an independent contractor if:

- “The worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact;

- The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

- The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed.”

Since its passage, AB5 has been criticized for making it difficult for gig economy firms to continue to operate and creating too rigid a system for categorizing workers. Companies and freelancers alike have expressed frustration with elements of the law that would make it difficult for them to continue to operate at all. For example, under AB5, a freelance musician could not play at a club in L.A. without being on the venue’s payroll as an employee, making them eligible for workers’ compensation, sick leave, and other benefits. Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez expressed concern that this requirement was driving clients to work with out-of-state freelancers to avoid the legal quagmire of AB5.

The new law passed last month exempts workers in much of the music industry from AB5, including recording artists, songwriters, producers, and promoters, allowing them to continue to work as freelancers for multiple clients. Freelance writers and photographers will also be exempt.

Last month’s change to the law will also expand the list of those who are exempt from AB5’s requirements to include youth sports coaching, interpreters, and those providing consulting services. It also expanded the professional services exemption to include appraisers, registered professional foresters, and home inspectors. Finally, it added landscape architects, manufactured housing sales, and several other occupations to the list.

A more innovative way forward

If so many exemptions must be made in order for California’s economy to continue to operate, this should cast doubt on whether AB5 creates a workable framework in the first place. Even after the exemptions, AB5 will still apply to many gig economy workers like ride-sharing drivers (pending the results of votes on Proposition 22 this fall). In fact, California is currently suing Uber and Lyft for alleged wage theft, arguing the companies must classify their workers as employees and provide all of the associated benefits, including paid sick leave, reimbursement of drivers’ expenses, and overtime and minimum wages.

California’s new law does little to address the deeper issue with how employment law is structured. The traditional arrangement in which a worker spends 40 hours a week working for one employer in exchange for a salary and benefits is no longer suitable for many Americans. Freelancing is becoming increasingly popular, with 57 million Americans freelancing in 2019 (35 percent of the total workforce) compared to 53 million in 2014.

A more promising way to give American workers and employers the flexibility they need is to detach benefits from a single employer model. One way to do that is through portable benefits. The Aspen Institute defines portable benefits as being “portable, prorated, and universal.” Portable benefits would move with a worker from job to job. Prorated benefits would be provided in proportion to work performed and could be funded by multiple clients. Universal benefits would be accessible by workers in every type of work arrangement.

New York’s Black Car Fund provides an existing example of portable benefits in action. The fund is a non-profit created by the state to provide workers’ compensation insurance and a driver death benefit to taxi cab drivers that pays out $50,000 to family members if a driver dies on the job. The fund covers over 70,000 affiliated drivers across the state and is funded by a 2.5 percent surcharge paid for by passengers. The benefits are portable as they move with drivers as long as they are employed by one of the Black Car Fund’s 300 member bases.

In a new policy paper from the Center for Growth and Opportunity, author Liya Palagashvili highlights key policy barriers currently standing in the way of greater adoption of portable benefits. She suggests that removing the provision of benefits as a deciding factor for how a worker is classified would be a promising step toward expanding benefits. Such a change would remove the current disincentive for platforms to provide some benefits to workers because they fear that doing so will risk the worker being categorized as an employee.

Another way to promote financial security among gig economy workers and freelancers would be to allow for universal savings accounts (USAs). In a recent policy paper, economist Adam Michel suggests the US tax code could be reformed to provide gig workers with tax-advantaged savings accounts similar to 401k accounts that traditional workers currently have access to. USA’s are simple, flexible savings accounts that would earn interest that would not be taxed. If gig workers had access to tax-advantaged savings accounts that they could draw from at any time, for any reason, this would provide greater financial stability to the workers who need it most.

In an ever-changing workplace, reforms that allow for more flexible arrangements between workers and employers are sorely needed. Instead of continuing to sort workers into two buckets, policymakers should examine ways to provide workers and employers with the opportunity to experiment with the arrangements that work best. Detaching benefits from employment would be a promising way to pave the path toward a more innovative future of work.