Executive Summary

Federal and state agencies tasked with forest management and wildfire suppression are overwhelmed. If these agencies are going to invest in real, timely forest management, they must consider innovative approaches to reducing wildfire risk. Qualified Insurance Resource(s) (QIRs) are a private wildfire response that provides wildfire mitigation efforts financed entirely by insurers willing to pay for a mechanism to reduce their losses when wildfires rage. As shown in Figure 1, QIRs are a viable tool to address the survivability of homes during a wildfire event, though they do not address necessary prevention mechanisms to decrease the probability of catastrophic wildfires. QIRs are deployable, scalable, and affordable to the average homeowner through standard homeowner policies. Nevertheless, these private mitigation resources face costly barriers that affect both consumers wishing to purchase insurance policies that provide QIR services and the QIR suppliers who face regulation that hinders their ability to access insured homes.

If these private resources are to be brought to scale and have a measurable impact on overall wildfire suppression efforts, agencies with authority over wildfire emergency responses will need to acknowledge this emerging industry and protect the insurance markets that give homeowners access to this important tool. The paper recommends regulatory changes that both improve access for QIRs and keep the insurance markets robust in the face of increasing risk from wildfires.1First and foremost, thank you to Wildfire Defense Systems, in particular David Torgerson and Nick Lauria, for allowing me to support such a worthwhile organization over the past seven years. I would like to thank the Center for Growth and Opportunity for giving this particular analysis a place to launch and Holly Fretwell for being a valuable intellectual contributor and friend throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dianna Rienhart and Jack Smith for their contributions in the editing process. The author has received no compensation from Wildfire Defense Systems or their affiliates in relation to this report or the research surrounding this report.

Figure 1. Qualified Insurance Resources providing fire mitigation services on an insured property during a wildfire incident.

Photograph courtesy of Wildfire Defense Systems.

Introduction

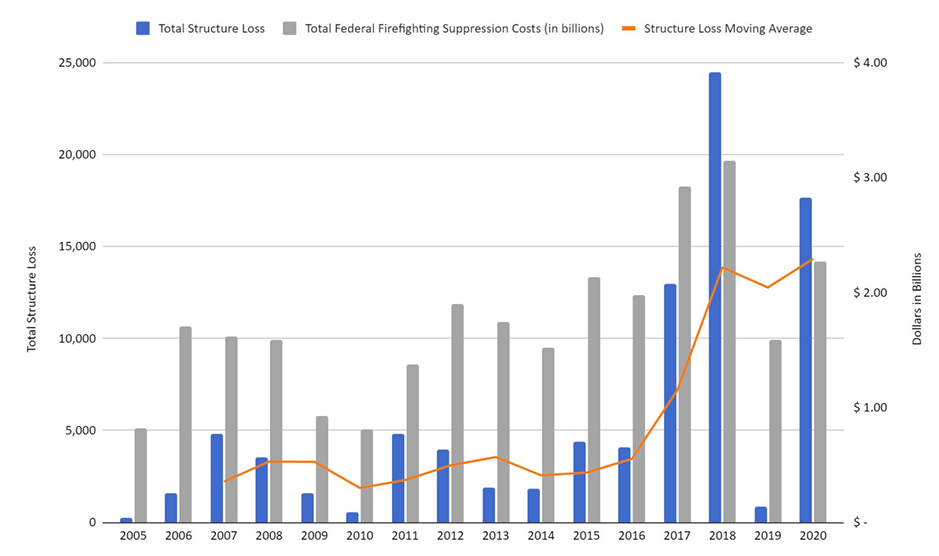

Over the past decade the federal government spent roughly 50 percent more on fire suppression efforts than the decade before.2According to the National Interagency Fire Center, the federal government spent $6.74 billion more on firefighting suppression costs from 2011 to 2020 than from 2000 to 2010. National Interagency Fire Center, “Federal Firefighting Costs (Suppression Only),” 2020, https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/statistics/suppression-costs. Fire suppression efforts now represent the largest share of the United States Forest Service’s (USFS) budget.3Holly Fretwell and Jonathan Wood, “Fix America’s Forests: Reforms to Restore National Forests and Tackle the Wildfire Crisis,” PERC Public Lands Report, April 12, 2021, https://www.perc.org/2021/04/12/fix-americas-forests-reforms-to-restore-national-forests-and-tackle-the-wildfire-crisis/. As figure 2 shows, despite escalated spending, structure losses due to wildfire have increased by an unprecedented 7,109 percent since 2005.4According to incident status summary data from the National Fire and Aviation Management FAMWEB, in 2005 wildfire structure losses were at 245, and it peaked in 2018 when 24,488 structures were destroyed, which included the homes destroyed by the devastating 2018 Camp Fire. Structure losses in 2020 were 17,663. The average percent increase per year is calculated to be 14.578 percent. Kimiko Barrett, “Wildfires Destroy Thousands of Structures Each Year,” Headwaters Economics, November 16, 2020, https://headwaterseconomics.org/natural-hazards/structures-destroyed-by-wildfire/#:~:text=Wildfire%20structure%20losses%20are%20increasing&text=From%202005%20to%202020%2C%20wildfires,over%20the%20last%2015%20years.

Figure 2. Wildfire Loss Trends and Federal Expenditures

Data from National Interagency Fire Center, “Federal Firefighting Costs (Suppression Only),” May 2021, https://www.nifc.gov/ fire-information/statistics/suppression-costs; EPA, “Climate Change Indicators,” April 2021, https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-wildfires; Kimiko Barrett, “Wildfires Destroy Thousands of Structures Each Year,” Headwaters Economics, November 16, 2020, https://headwaterseconomics.org/natural-hazards/structures-destroyed-by-wildfire/#:~:text=Wildfire%20structure%20losses%20are%20increasing&text=From%202005%20to%202020%2C%20wildfires,over%20the%20last%2015%20years.

With average annual acreage burned and structure losses at an all-time high5Congressional Research Service, “Wildfire Statistics,” In Focus, May 4, 2021, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10244.pdf., agency resources are increasingly being prioritized toward fire containment.6The three “incident priorities” for federal and state wildfire agencies during a wildfire event are life safety, incident stabilization, and property conservation (LIP). See: Structure Fire Operations. September 2015. Firescope. https://www.glendaleca.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/35040/636143619710370000 Since the USFS is tasked with both fire suppression and forest management, these efforts to suppress fires and protect structures come at a cost to necessary and overdue forest management projects.7 Fretwell and Wood, “Fix America’s Forests.”

To make matters worse, home building in what is known as the “wildland-urban interface” (WUI)— homes adjacent to forested lands—is expanding rapidly, with an estimated 50 million homes currently in the WUI.82020 estimates based on: Marshall Burke, Anne Driscoll, Jenny Xue, Sam Heft-Neal, Jennifer Burney, and Michael Wara, “The Changing Risk and Burden of Wildfire in the US” (NBER Working Paper No. 27423, National Bureau of Economics Research, Cambridge, MA, June 2020). The significant growth in federal wildfire expenditures in response to this expansion has certainly benefited property owners, serving as an implicit subsidy for homeowners adjacent to national forests and other federal lands, albeit to varying degrees depending on development density.9Patrick Baylis and Judson Boomhower, “Moral Hazard, Wildfires, and the Economic Incidence of Natural Disasters” (NBER Working Paper No. 26550, National Bureau of Economics Research, Cambridge, MA, December 2019). This research argues that residential development adjacent to forested lands dramatically increases firefighting costs and that efforts to protect private properties account for the majority of federal wildfire firefighting expenditures. The paper argues that these expenditures represent a significant transfer to these homeowners.

Rather than relying on the limited resources provided by government agencies, owners of private property in forested lands can and should play a bigger role in wildfire mitigation and suppression. Agencies tasked with forest management should consider innovative approaches that integrate these stakeholders in order to alleviate their budgetary pressure and free funds to invest in real, timely forest management.10See SDA, Forest Service, The US Forest Service: An Overview, 2008, 27–30, https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/legacy_files/media/types/publication/field_pdf/USFS-overview-0106MJS.pdf.

One often overlooked remedy comes from private insurance companies and their contributions to reduce the damages from wildfire incidents.11This overview provides insight into the Forest Service’s strategic direction and tools considered to combat wildfire. In it there is no mention of QIRs. USDA, Forest Service: An Overview. Known as Qualified Insurance Resource(s) (QIR), this industry is made up of private response teams funded and contracted entirely by insurance companies looking to protect their insured properties from damage during a wildfire event. Typically comprising firefighting crews, wildland engines, tenders, hand crews, and fire liaison officers, these teams have a mission to mitigate the impacts to insured homes or commercial structures that are threatened by a wildfire incident. To do this, teams must enter restricted areas within a particular wildfire’s path, often in evacuation zones, and provide mitigation services on insured properties and their surrounding areas in advance of that wildfire.12The process to trigger an analysis of whether QIR services are needed on a wildfire event includes the identification of insured properties within an evacuation zone. Next, QIR risk analysts will assess whether each home within the evacuation zone is threatened and to what degree. When a proprietary threshold is met, the final consideration will be whether QIRs are available during the wildfire event.

As shown in Figures 3 and 4, this includes the removal of combustible fuels, construction of fuel breaks, applications of fire retardant and firefighting foam, the elimination of entry points for fire embers, and finally, returning for post-mitigation services after the wildfire has passed through the area.13David Torgerson (industry expert and CEO of Wildfire Defense Systems), interview by the author, August 4, 2020, Bozeman, MT. In this way, QIRs significantly amplify the resources available to protect structures during a wildfire event but do not engage in any preventative activities such as fuels management or prescribed burns that will reduce the risk of a wildfire starting in the first place.

Figure 3. Shows examples of the mitigation work that QIRs will provide to insured properties within a wildfire evacuation zone in advance of a wildfire. These services are deployed to insured homes when the home is threatened by a wildfire and in advance of the impending risk.

Photographs courtesy of Wildfire Defense Systems.

Figure 4. Shows an example of the post mitigation work that QIRs will provide to insured properties after the wildfire has passed. These are known as “mop up” services.

Photograph courtesy of Wildfire Defense Systems.

As QIR services expand across the nation, agencies tasked with wildfire suppression benefit. Although these services are not a replacement for forest management and in no way mitigate the need for fuels management, QIRs provide targeted mitigation efforts to insured homes and properties at risk during a wildfire event, and they do so without using government resources. This action shifts property and structure conservation away from government agencies and into the private sector. Because these efforts do not need to be duplicated by the USFS or any other government agency, they free up federal and state appropriations that could be used for forest management.

Additionally, increasing reliance on private insurance companies provides homeowners with a market mechanism to reduce their risk of damage from wildfire and better aligns the cost of wildfire mitigation with the homeowners within the wildland-urban interface.

Nevertheless, there are challenges associated with tapping into these private, insurer-funded wildfire resources. To begin with, private resources devoted to wildfire mitigation come in different forms, and the differing types of private resources can be confused for one another. This misunderstanding leads to institutional barriers that limit the contributions from insurer-funded wildfire mitigation. Some of the institutional barriers limit the ability of insurer-funded wildfire response teams to act during wildfire events. Other barriers exist because government-instituted price controls on homeowners insurance rates push insurers out of the marketplace and effectively make these services unavailable in certain marketplaces.

If insurer-funded wildfire mitigation is going to be brought to scale and have a significant impact on the overall cost of wildfire, barriers to providing and using these resources will need to be reduced, and agencies will need to acknowledge the advantages of this innovative approach to fighting fires.

Insurer-Funded Wildfire Response

Insurer-funded wildfire mitigation is the second largest of three existing market mechanisms that use private resources to mitigate and suppress wildfire.14David Torgerson (industry expert and CEO of Wildfire Defense Systems), interview by Monique Dutkowsky and Holly Fretwell October 20, 2020, Bozeman, MT. The majority of what is classified as “private” sector resources comes in the form of federally contracted firefighting crews and equipment, which are used as reinforcements when agency resources are overwhelmed. These types of private resources, arguably, do not free federal resources for forest management since these resources are funded by federal appropriations. A much smaller portion of private resources, roughly 1–3 percent, comes in the form of private fire suppression services purchased directly by large landowners, homeowner associations, and developers.15Torgerson, interview, October 20, 2020. These private resources focus on protecting especially valuable private property and are not necessarily recognized or certified by professional associations.16This type of response does not cost the government, and if these response teams are officially recognized by local agencies, they can be used by a wildfire incident commander and can provide increased response. It is important to note that homeowners associations and developers operate under different parameters than landowners who operate their own wildfire resources. First, HOAs and developers in jurisdictions without adequate public fire services can, through certified HOA dues, create certified private fire brigades that are designated as a “recognized resource” under state law. As a result, these private fire brigades can be used by a wildfire incident commander and provide increased response. By contrast, private firefighters working for private landowners are not a “recognized resource,” are not certified, and only respond to wildfires on their clients’ properties.

Of the three existing private sector contributions, insurer-funded wildfire mitigation has the greatest potential to expand, significantly decrease structure losses, and effectively augment federal wildfire responses.

One advantage of a QIR is its accessibility and affordability. QIR protection is paid entirely by the private sector—in this case, insurers with an incentive to reduce the damage from wildfire. But unlike private resources contracted by large landowners, this service is accessed by property owners through their standard commercial and homeowners insurance policies. Moreover, because it significantly reduces the probability of a loss, these services come at no additional cost to the policyholder.17Since 2008, participating insurance companies have provided wildfire response services as a standard provision within a homeowners insurance policy. This is paid by the insurer rather than the policyholder. Metcalf, Hunter (legal counsel for QIRs), interviews by the author, August 17, 2017 and July 23, 2021, Bozeman, MT. Because the insurer is able to spread the cost of these private mitigation efforts across many insured individuals, it is accessible and affordable to any homeowner with standard homeowner’s insurance. This affordability means that this tool has the potential to rapidly scale up, giving more homeowners access to a market tool that can reduce their risk from wildfire without reliance on government. 18Although there is no minimum or maximum limit on the value of the home, the average total insured value for properties covered by QIRs through their homeowners insurance policy is $800,000. This includes the sum of the full replacement cost of the insured property, including the value of property, inventory, and equipment. In aggregate, 97.5 percent of properties covered by QIR are owned by individuals categorized as middle class according to the PEW Research Center’s definition.

Unlike other approaches to reducing wildfire impacts, this market-based tool is already deployed and scalable without the need for government resources.19Fretwell and Wood, “Fix America’s Forests.” In fact, despite regulatory hurdles, this industry is already having a measurable impact on overall wildfire mitigation efforts.20Monique Dutkowsky, “A Private Solution to Wildfire Risk,” Property and Environment Research Center, September 14, 2020, https://www.perc.org/2020/09/14/a-private-solution-to-wildfire-risk/. Wildfire Defense Systems (WDS)—the nation’s leading provider of QIRs—has responded to more than 900 wildfire incidents in 20 states since its inception in 2008, and once access is granted, WDS has a 99.9 percent success rate.21More details on Wildfire Defense Systems and their contribution to QIRs can be found at their website, https://wildfire-defense.com/. With more than 140 wildland engines and 220 professionally certified firefighters, in 2020 WDS successfully provided structural mitigation and protection to roughly 10,000 homes and commercial buildings. To put that in perspective, in 2020 the total structural damages from western wildfires amounted to 17,663 structures.22Kimiko Barrett, “Wildfires Destroy Thousands of Structures Each Year.” Without WDS’s efforts, loss rates had the potential to be 56.6 percent higher. Additionally, WDS partners with more than two dozen top insurance companies to service more than half of all California homes and a total of eight million properties throughout the West.23Insurance providers who invest in QIRs decide on a state-by-state basis in which states they wish to provide this coverage. After the states with the highest number of at-risk properties are determined, every policyholder in the state is auto-enrolled in the QIR service. In 2020 alone WDS’s contribution to loss prevention was estimated at $1 billion. This puts WDS on the scale of a western state firefighting response agency and ranks the company as the third largest emergency response and resource protection entity in the nation, behind California’s Cal Fire.24Marshall Zelinger, “Insurance-Based Firefighting: These Crews Don’t Go out to Save Every House.” 9News Denver, May 26, 2021, https://www.9news.com/article/news/local/wildfire/insurance-based-firefighting-colorado-house-wildfire/73-cd9e39bf-c516-4e14-9f39-063b067367c2.

With a mission to protect private property and a response that is on the scale of a western state agency, QIRs amplify the response to wildfire incidents, shift the burden of wildfire mitigation onto landowners most threatened by wildfire, and decrease the required federal response to conserve property. Brought to scale, this type of model has the potential to reduce the cost of wildfire, allowing Forest Service funds that are currently devoted to suppression to shift to forest management projects that can help prevent wildfires from occurring.

Institutional Barriers to QIRs

Supply-Side Barriers: Bureaucratic Red Tape That Stops Engines in Their Tracks

25Many of the ideas in this section are discussed by the author in Monique Dutkowsky and Holly Fretwell, “California Can Learn from Colorado about Protecting Homes from the Risk of Wildfires,” California News Times, November 13, 2020, https://californianewstimes.com/california-can-learn-from-colorado-about-protecting-homes-from-the-risk-of-wildfires-pasadena-star-news/37990/; and Monique Dutkowsky and Holly Fretwell, “California Can Learn from Colorado about Protecting Homes from the Risk of Wildfires,” The Orange County Register, November 13, 2020, https://www.ocregister.com/2020/11/13/california-can-learn-from-colorado-on-protecting-homes-from-wildfire-risks/. Despite the fact that QIR firefighters have the same training and certifications as government agency firefighters, there are significant barriers associated with using these private resources.26QIR crews are National Wildfire Coordinating Group certified and are members of the International Association of Fire Fighters Union. Note that these private crews are prohibited from providing aerial support or creating backburns; thus, portions of the certification are not available to them. Although these professional firefighting crews and equipment are available during a wildfire event, they are not always granted access. In fact, the default policy is to treat QIR personnel the same as the general public, requiring them to evacuate. Any access to threatened, insured properties is currently granted on a case-by-case basis with the controlling Incident Management Teams.27When a wildfire exceeds the capabilities of a jurisdictional agency, the National Incident Management System will establish an Incident Management Team to manage the event. The IMT will be made of varying federal, state, and local agencies and will designate an Incident Commander as the authority on the wildfire event. The IMT retains ultimate say for all things on the incident, including access by private resources. For more on IMTs see: International Association of Fire Chiefs, Guidelines for Managing Private Resources on Wildland Fire Incidents, https://www.iafc.org/docs/default-source/1assoc/iafcposition-wildlandresourceutilizationguidelines.pdf?sfvrsn=bc0cd80d_0&download=true. Since each wildfire incident will have a different governing body based on a number of factors including jurisdictional authority, resources, and time on the event, there is no centralized entity that determines which organizations can gain access and how. As a result, each wildfire incident is a negotiation between a QIR incident liaison and the Incident Commanders. This process creates unnecessary delay that amounts to even more potential losses. 28Based on current guidelines, which come from the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) and have been adopted by NWCG, the direction for Incident Commanders (ICs) is to consider granting access to QIRs on a case-by-case basis. The IAFC and NWCG guidelines do not provide for a process to prequalify for access to an incident or provide standardized operating procedures once access is granted. Current fire service guidelines amplify the problem with varying IMT procedures, critical delays in access, inconsistent use of QIRs, and confusion by IMTs as to how QIRs should be managed when evacuation zone access is granted.

There is no governing body granting access to wildfire incidents across the nation, so no entity has the means or authority to coordinate the web of professional associations (e.g., National Interagency Fire Center) and federal, state, and local agencies. This means that under the current state of regulations, insurers must invest in QIRs without a guarantee that crews will be granted access to insured properties. This uncertainty undoubtedly limits insurers’ willingness to pay for these services and, thus, the impact QIRs can have on wildfire mitigation.

Even when QIR personnel are granted initial access, significant barriers remain. When access is granted, the process is often difficult because Incident Management Teams lack protocols for granting access or integrating resources. This negotiation process makes exchanging information and conveying permissions slow and difficult, which can lead to costly delays in deploying private teams to threatened properties. Additionally, the ad hoc method of engaging with Incident Management Teams means that there is less consistency and oversight across states and wildfire events regarding how and when QIRs can operate.

Uncertainty leaves this emerging industry vulnerable to policies that threaten to end this important market-based approach to saving homes. For example, in 2018 California passed legislation aimed at creating additional regulatory hurdles and oversight for the private firefighting industry with the potential to prevent QIRs from accessing their insured properties.29Cal. Health and Safety Code § 14865–14868 gave various state agencies, including the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, CAL OES, and FIRESCOPE, the authority to regulate and set limitations on QIRs. Note that the proposed regulations under this authority were only released recently, so the full impact of the law is unknown and yet to come to fruition. This is a clear example of how fragile this emerging industry is to sudden state regulations driven by misconceptions about QIRs and how they differ from other, uncertified private wildfire responses.30After a landowner purchased direct and privately held firefighting resources, these uncertified private citizens started a backburn that caused the Glass Fire of 2020 to spread. Shortly after this, a state committee that was designated under Cal. Health and Safety Code § 14865–14868 began to act for the first time since its inception. Jay Barmann, “Cal Fire Investigates Vigilante Backfire Activity in First Days of Glass Fire,” SFist, October 6, 2020, https://sfist.com/2020/10/06/cal-fire-investigates-vigilante-backfire-activity-in-first-day-of-glass-fire/. Nevertheless, with a better understanding of insurer-funded resources and the right regulatory changes, state governments can make improvements just as quickly as they add burdensome hurdles. 31Code 14867 grants authority to develop standards and regulations for privately contracted fire prevention resources during an active fire incident in California and sets forth limitations on private resources. Code 14868 grants the same agencies authority to develop regulations governing use of the equipment by private resources. A full description of the legislation is available here: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=HSC&division=12.&title=&part=4.5.&chapter=&article=.

Demand-Side Barriers: Price Regulations That Stunt the Market for Private Wildfire Response

Unfortunately, at-risk homeowners who wish to purchase an insurance policy that includes access to this market response to wildfire risk face an uphill battle in a key western state. In California, homeowners face a dual problem: historically high risk to their homes from wildfires and difficulty obtaining quality homeowners insurance. This damaging combination has been largely caused by California’s approach to regulating the insurance industry.

The California Department of Insurance regulates insurance premiums to keep prices artificially low through an arduous price approval process that sets a maximum allowable premium, limits the distribution between high and low premiums, dand mandates that insurers use outdated historical data to project future expected losses.32Dutkowsky and Fretwell, “California Can Learn” California News Times; Dutkowsky and Fretwell, “California Can Learn,” The Orange County Register; Lloyd Dixon, Flavia Tsang, and Gary Fitts, The Impact of Changing Wildfire Risk on California’s Residential Insurance Market, California Natural Resources Agency Report No. CNRA-CCC4A-2018-XXX, August 2018. The result is that in the face of unprecedented losses, claims have overwhelmed what insurers are legally able to charge in premiums.33Ronald Bailey, “Can Fire Insurance Manage Wildfire Risks in California?,” Reason, September 18, 2020, https://reason.com/2020/09/18/can-fire-insurance-manage-wildfire-risks-in-california/; Don Jergler, “Industry Representative Puts Fire Insurance Availability at Feet of Commissioner,” Insurance Journal, December 6, 2019, https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/west/2019/12/06/550633.htm. With wildfire loss predictions increasing and the California Department of Insurance resorting to moratoriums that force insurers to maintain coverage, insurers have begun to pull out of the California market to avoid insolvency, leaving hundreds of thousands scrambling to find coverage.34“After wildfires, hundreds of thousands of Californians can’t get insurance,” CBS News, August 30, 2019, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/wildfires-california-homeowners-insurance-hard-to-find-due-to-magnitude-of-massive-wildfires/; “California Department of Insurance Commission Protects More than 2 Million Policyholders Affected by Wildfires from Policy Non-Renewal for One Year,” Sierra Sun Times, November 5, 2020, https://goldrushcam.com/sierrasuntimes/index.php/news/local-news/26443-california-department-of-insurance-commissioner-protects-more-than-2-million-policyholders-affected-by-wildfires-from-policy-non-renewal-for-one-year. Often, all that is left for homeowners is the California Fair Plan—a basic, last-resort insurance option that does not offer insurer-funded wildfire protection.35The Fair Plan, created by the California legislature in 1968, is a state-mandated association of all California property insurers. It is designed to offer high-risk homeowners and renters basic coverage options. Ed Leefeldt, “After Wildfires, Hundreds of Thousands of Californians Can’t Get Insurance,” CBS News, August 30, 2019,

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/wildfires-california-homeowners-insurance-hard-to-find-due-to-magnitude-of-massive-wildfires/#:~:text=An%20estimated%20350%2C000%20California%20home,the%20situation%20will%20get%20worse.

By contrast, Colorado allows for premium adjustments that better reflect differing levels of wildfire risk.36Colo. Code Regs. § 3 CCR 702-5 (2021). Like California homeowners, Colorado homeowners in extreme wildfire risk zones can be denied or lose fire insurance coverage. When this occurs, unlike in California, Colorado homeowners can then opt into local mitigation programs that assist and certify them through a process of modifying their home and their surrounding property to reduce the risk from wildfire. In exchange, many insurers in Colorado have agreed to cover certified homes.

With nearly 776,000 homes in the United States at extreme risk of wildfire damage, and with the majority of those homes located in California, California homeowners could benefit greatly from homeowners insurance coverage that includes insurer-funded wildfire protection.37CoreLogic produces geospatial estimates of the number of at-risk homes and groups them by city. Gabrielle Paluch, “Report: California Has Most Homes at Extreme Risk of Wildfire Damage This Season,” Palm Springs Desert Sun, September 12, 2019, https://www.desertsun.com/story/news/environment/2019/09/12/california-has-most-homes-extreme-risk-wildfire-damage-season/2283377001/ and https://www.corelogic.com/downloadable-docs/widfire-report-200910-version-2.pdf. Allowing premiums to reflect true risk of wildfire damage would also create incentives for homeowners and developers to invest in home-hardening efforts that make homes more fire resistant and to develop in less risky areas—choices that are necessary to reduce the cost of wildfire for individuals and taxpayers.38CalFire, “Hardening Your Home,” February 2019, https://www.readyforwildfire.org/prepare-for-wildfire/get-ready/hardening-your-home/. Nevertheless, when insurers leave the California market in response to binding price controls, they take their private wildfire protection with them, leaving homeowners with less protection and more risk.

Policy Recommendations

To improve access to insured properties and integrate Qualified Insurance Resources into wildfire responses, federal and state agencies with authority over wildfire emergency responses—including United States Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Montana’s Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services—the following actions are recommended:

- Consider how QIRs can shift costs from their agencies to insurers and at-risk landowners with an incentive to mitigate against wildfire risk.

- Engage in a standard Cooperator Agreement with QIRs in order to avoid costly delays stemming from time spent negotiating rather than deploying resources. These agreements should include these key components:

- Recognize QIRs as an official resource inside the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the Incident Command System.39NIMS is the coordinating body under the Department of Homeland Security that facilitates and guides all levels of government during a national disaster. During a wildfire event, NIMS sets up the framework for the Incident Command System. Under the NIMS guidelines, outside agencies can be recognized during a wildfire incident under the cooperating Agency Clause. Although this clause is typically deployed for public agencies outside the jurisdiction of the wildfire, the clause leaves open the possibility of its use with private organizations. 40FEMA, National Incident Management System, 3rd ed., October 2017,pg. 1, 26, & 68 (Last viewed on June 22, 2021): https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/nims.

- Provide agencies with authority over wildfire emergency responses with a means to grant prequalified, consistent, and immediate access to threatened, insured properties affected by wildfire incidents that are safe enough for incident resources to operate.

- Design universal, standard operating procedures for granting access and integrating insurer-funded resources into the Incident Management Team.

- Recognize QIRs as an official resource inside the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the Incident Command System.39NIMS is the coordinating body under the Department of Homeland Security that facilitates and guides all levels of government during a national disaster. During a wildfire event, NIMS sets up the framework for the Incident Command System. Under the NIMS guidelines, outside agencies can be recognized during a wildfire incident under the cooperating Agency Clause. Although this clause is typically deployed for public agencies outside the jurisdiction of the wildfire, the clause leaves open the possibility of its use with private organizations. 40FEMA, National Incident Management System, 3rd ed., October 2017,pg. 1, 26, & 68 (Last viewed on June 22, 2021): https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/nims.

Taking these steps would streamline the process of granting QIRs access to the properties they are designed to protect and avoid delays that can cost property owners their homes and businesses. The Cooperator Agreement establishes much-needed guidelines that would allow for quick access and resolution of conflicting operating procedures. Finally, integrating QIRs as a recognized resource will allow incident command teams to clearly distinguish certified private partners from uncertified private citizens with firefighting equipment. Finally, engaging in Cooperator Agreements will by default define and limit the scope of what QIRs can do and give federal and state agencies the confidence to rely on QIRs to help reduce the impact from wildfire using partners they can trust.

To increase and protect homeowner access to insurer-funded wildfire mitigation, state regulators overseeing homeowner and commercial insurance should take the following steps:

- Revive and bolster homeowners insurance markets by reducing binding price controls and allowing premiums to adjust to wildfire risk.

- Allow private insurance companies to deploy updated wildfire risk models that rely less on historical data as the main predictive mechanism for premium rates.

- Follow Colorado’s lead in offering local wildfire mitigation programs that assist property owners in successfully mitigating the risk from wildfire.41To learn more about Colorado’s wildfire mitigation programs, see Colorado Project Wildfire, Colorado Property and Insurance Wildfire Preparedness Guide, 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zXD7CHD9sy7kp5l-0fqkwEBotS7BVyLP/view, and Boulder County, “Our Program,” Wildfire Partners, 2020, https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.wildfirepartners.org/our-program/&sa=D&source=editors&ust=1621538436363000&usg=AOvVaw0X0qgH1S5xqNA_sL-j1c9U.

When homes are certified through the program, agencies should work with insurers to guarantee these homeowners receive coverage at discounted rates, thus, avoiding any potential price spikes. States should rely on the initial rising prices to incentivize homeowners towards these mitigation programs. - Create incentives for insurance companies to tie private fire mitigation services into their policies. This might include allowing participating insurance companies the ability to charge premium rates that reflect true wildfire risk. This would provide increased dedicated protection for insured properties, reduce losses when wildfires rage, and reduce the probability that insurers will exit a risk-prone area altogether, leaving homeowners without coverage.42Dutkowsky and Fretwell, “California Can Learn” California News Times; Dutkowsky and Fretwell, “California Can Learn,” The Orange County Register.

Implementing these recommendations will increase the probability that insurers will continue to operate in western states, despite predictions that wildfires will get significantly larger, more destructive, and more frequent in the coming decade. Homeowners depend on a robust insurance market to access these highly effective protections, since insurers fund QIR services. Allowing premiums to adjust to true wildfire risk would allow insurers to invest in QIRs and provide incentives for homeowners and developers to modify their behavior and invest in home-hardening efforts and structural characteristics that are fire resistant, all without the need for government resources.

Creating more wildfire mitigation programs like Colorado’s would reduce participating homeowners’ risk levels, which in turn allows insurers to decrease premium rates to reflect the reduction in the risk level. When enough homes in a region respond to this incentive by investing in mitigation, insurers are able to remain in the marketplace. Without these kinds of price reforms that connect insurance prices to risk levels, homeowners lack the incentive to act in ways that reduce the probability of damage. Thus, property damage risk levels increase throughout a region and push insurers out of the marketplace.

Conclusion

Supporting private sector, insurer-funded efforts during wildfire incidents and reducing their associated barriers is an important step toward increasing the overall resources devoted to reducing losses due to wildfire. With reforms, private sector wildfire contributions could alleviate budgetary pressure at the federal and state levels and provide more effective structural mitigation protection. If the private sector focused on protecting homes, this would free up federal and state resources to focus on programs to better manage the forests to prevent catastrophic fires.

Nevertheless, for reforms to be effective, consumers need to be able to access this product in the marketplace. Regulators in extreme wildfire risk locations should allow for robust homeowner insurance markets by allowing premium adjustments that better reflect differing levels of wildfire risk. Allowing rates to rise according to true risk will not only provide incentives for homeowners to invest in mitigation, but it will also provide necessary funding for insurance companies to invest in Qualified Insurance Resources.43Dutkowsky and Fretwell, “California Can Learn” California News Times; Dutkowsky and Fretwell, “California Can Learn,” The Orange County Register. Homeowners and developers facing higher insurance rates will then have an incentive to invest in home-hardening efforts and to develop in less risky areas.44Monique Dutkowsky and Holly Fretwell, “Fire Insurance Regs Hurt California Homeowners,” November 4, 2020, https://insidesources.com/fire-insurance-regs-hurt-california-homeowners Combined, these efforts will motivate insurers to stay in the marketplace despite increased wildfire activities.

Saving taxpayers and protecting homes, this solution is a win-win for landowners, insurers, and policymakers. To keep this private approach alive, we’ll need protections that fan the flames of innovation.