Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit U.S. households and businesses very hard. Particularly hard hit are small businesses, many of which have now been closed for over two months with minimal if any, income or public support. The U.S. small business sector is increasingly made up of immigrant-founded firms, and are particularly prevalent in the COVID-19 hotspot locations in New York, New Jersey, California, and those Florida.1Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Immigrant entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the Survey of Business Owners 2007 & 2012,” Research Policy 49, no. 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103918. As the U.S. economy begins to reopen, what is the role of these immigrant-founded firms in the recovery effort? And what policies will make them more (or less) successful in bringing back the jobs to those hard-hit areas?

While making exact predictions in these highly uncertain times is impossible, we can draw from recent research to depict a reasonably well-informed view of the role of immigrant entrepreneurs in the U.S. economy during the recovery phase in 2020 and beyond.

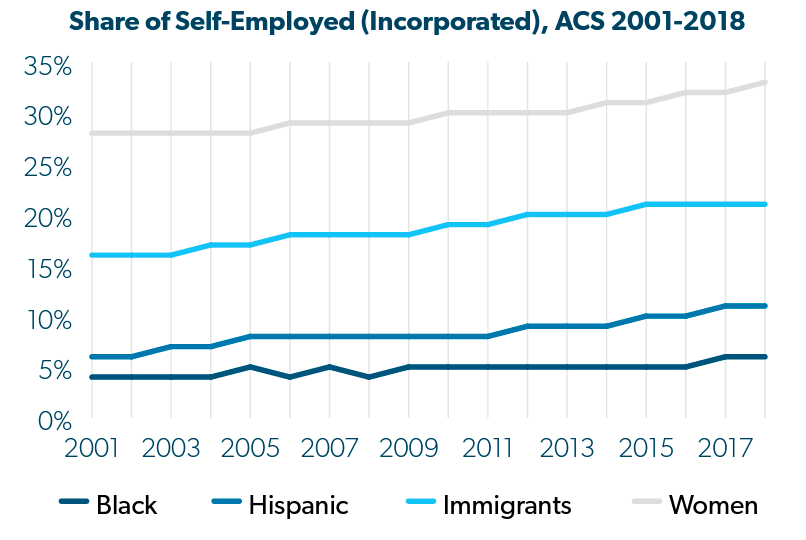

First, it is important to remember that the “entrepreneurial pool,” the backbone of the small-business sector, has continually become more diverse over the last two decades. The share of immigrant and female entrepreneurs has increased, along with the shares of Latino and black owners, as well as the owners from ethnic backgrounds such as Mexican, Chinese, and Indian. New firm formation and job creation are currently much more dependent on these diverse entrepreneurs than it was in the 1990s and early 2000s.2Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Firms and Founders: Has the American Entrepreneur Changed Over the Past Decades?” (2020), Mimeo. More inclusive policies and programs may be warranted to reach this diverse group of entrepreneurs. One example of such is the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) that was created as part of the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010, with a specific objective to expand access to credit to businesses in low- and moderate-income areas, minority and other underserved communities.

Figure 1. Shares of Self-Employed Women, Immigrants, Blacks, and Hispanics (2001-2018)3Author calculations of American Community Survey (ACS) Data

Second, immigrant entrepreneurs alone are responsible for a lot of new hiring among young firms. They create roughly one in four of all jobs in those young firms, but the share goes to 40 percent and above in many places, such as the Silicon Valley, New York City, and other tech hubs. This is significant given that young firms are responsible for a disproportionate number of newly created jobs, and much of the dynamics of our economy takes place in those firm cohorts.4John C. Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda, “Who Creates Jobs? Small Versus Large Versus Young,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 95, no. 2 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00288. Ensuring the viability of already existing young firms is critical if we want them to continue their role as the job creation engine. Likewise, fostering an environment for firm birth (whether immigrant-founded or otherwise) helps to make the recovery more robust in the medium to short run. During the recovery phase, this could, for example, include more broadly introducing programs such as the Self-Employment Assistance (SEA) programs that already exist in five states to enable unemployed workers to start their own business that creates a job for themselves and others.5“Self-Employment Assistance,” November 1, 2019, United States Department of Labor, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/self.asp#:~:text=Self%2DEmployment%20Assistance%20offers%20dislocated,starting%20their%20own%20small%20businesses; “Self-Employment Assistance (SEA),” United States Department of Labor, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/factsheet/SEA_FactSheet.pdf.

Third, immigrant-owned firms are particularly prevalent in the service sector (e.g., accommodation and food services, and other personal services), as well as many other sectors that were hardest hit by the pandemic.6Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Immigrant entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the Survey of Business Owners 2007 & 2012,” Research Policy 49, no. 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103918. Notably, the service sector establishments that are minority- or immigrant-owned tends to have the smallest amount of capital to survive any extended closures or other shocks. These firms, once open, hire a dependable stream of employment given the very labor-intensive nature of the business. It is, therefore, essential to ensure that these firms can reopen successfully or otherwise, many of the jobs we have relied upon will be lost. The issues that may need solving include, among others, delayed rental and tax payments, expired licenses, and any inspections required to reopen with state-mandated COVID-specific safety measures. For example, a natural solution to the backlog in licensing would be to extend all existing licenses for 12 months and focus efforts on enforcing the COVID-19 related regulations. In general, immigrants struggle more with occupational licensing in many areas, and additional assistance for non-native speakers would be warranted during the recovery phase and beyond. These issues may be local in nature or may require more coordinated action at the state or federal level.

It is likewise worth noting that many immigrant-founded firms are extremely dependent on being able to hire immigrant labor either through the skilled-focused H1-B program, or through the various seasonal worker programs, as well as co-ethnic immigrants who are already in the country on various work visas, green cards, and some already naturalized.7Co-ethnic hiring varies greatly depending both on the ethnicity of the business founder as well as the local supply of co-ethnic labor. See: Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Whose Job Is It Anyway? Co-Ethnic Hiring Patterns Among Immigrant Founded Firms in the United States,” (2020), Mimeo. When firms reopen and are allowed to bring back their workers, it is critically important that immigration policies do not make it harder to re-employ this pool of labor. Many of the federal immigration programs were either halted or have become severely backlogged during the pandemic.

Compared to native-owned businesses, immigrant-owned firms are also more focused on exporting and other international activities. For such companies, much of their business income can be derived from that international channel.8Kerr and Kerr, “Immigrant entrepreneurship.” When beginning to open up international travel and trade routes, it is crucial to make sure that policies do not undermine the ability of businesses to engage in the international markets.

In terms of already existing policies directly aimed at economic recovery from the COVID-crisis, it is unclear as to how much the immigrant-owned businesses have been able to benefit from the federal recovery effort and small business loans. Specifically, reports in many news outlets indicate that minority- and immigrant-owned businesses have been unable to participate in the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) either due to some program requirements or simply because the program ran out of money before most of these small businesses were able to apply. In addition, program regulations are generally written in language that is not easily accessible to non-native English speakers. To make sure Federal assistance is more broadly available, local communities who know their small business communities could consider, e.g., offering consultation for applicants. These issues are worth investigating and rectifying, given the likelihood that these mostly small businesses will play a key role in the economic recovery and re-creation of jobs.

In sum, the importance of immigrant entrepreneurs as firm founders and job creators has grown significantly over the last few decades. Immigrants will have a major part in the economic recovery from the COVID-crisis. The issues faced by immigrant-owned firms are the very same ones that native owners of small businesses struggle with. Yet they also have some specific concerns that could be addressed in order to ensure a successful reopening of existing firms and a launch of new immigrant-founded enterprises. U.S. economic recovery will be much smoother if policymakers can readily respond to those needs at the local, state, and federal levels.

References

1. Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Immigrant entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the Survey of Business Owners 2007 & 2012,” Research Policy 49, no. 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103918.

2. Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Firms and Founders: Has the American Entrepreneur Changed Over the Past Decades?” (2020), Mimeo.

3. Author calculations of American Community Survey (ACS) data.

4. John C. Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda, “Who Creates Jobs? Small Versus Large Versus Young,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 95, no. 2 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00288.

5. “Self-Employment Assistance,” November 1, 2019, United States Department of Labor, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/self.asp#:~:text=Self%2DEmployment%20Assistance%20offers%20dislocated,starting%20their%20own%20small%20businesses; “Self-Employment Assistance (SEA),” United States Department of Labor, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/factsheet/SEA_FactSheet.pdf.

6. Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Immigrant entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the Survey of Business Owners 2007 & 2012,” Research Policy 49, no. 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103918.

7. Co-ethnic hiring varies greatly depending both on the ethnicity of the business founder as well as the local supply of co-ethnic labor. See: Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Whose Job Is It Anyway? Co-Ethnic Hiring Patterns Among Immigrant Founded Firms in the United States,” (2020), Mimeo.

8. Kerr and Kerr, “Immigrant entrepreneurship.”