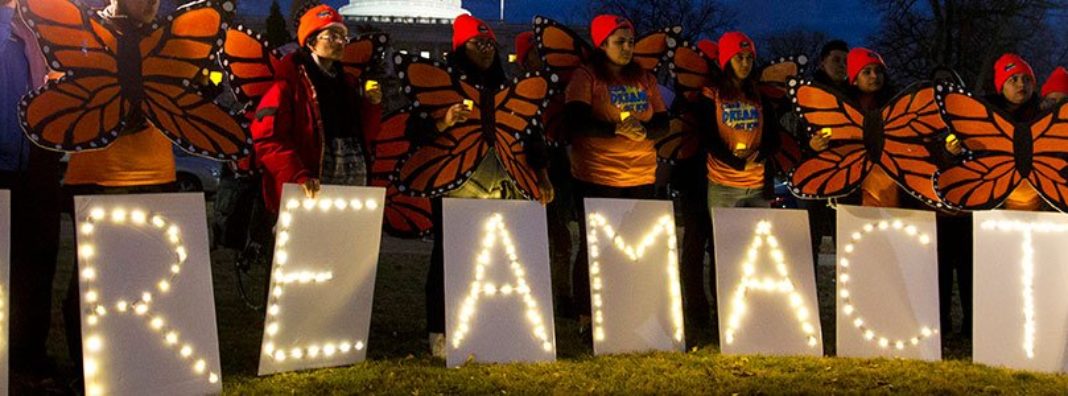

As the government faces another shutdown debate, immigration reform is once again a sticking point. During his State of the Union address last Tuesday, President Trump issued a framework for a deal. The most exciting aspect of his plan is the offer to more than double the number of people protected by Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) from about 700,000 to 1.8 million with the possibility of a path to citizenship for these undocumented immigrants. In exchange, Trump wants about $30 billion in funding for a border wall with Mexico and new restrictions on legal immigration.

For Democrats and moderate Republicans, lowering the caps on how many immigrants can legally enter the United States appears to be a nonstarter. However, given the economic benefits of immigrants, and especially the “Dreamers” that fall under DACA, trading legal recognition and future citizenship of 1.8 million immigrants for border wall funding might be a worthwhile deal for pro-immigration members of Congress. Absent any cutbacks on legal immigration, the economic benefits of expanding DACA could be well above the $30 billion figure for the wall.

Economists broadly agree that workers’ pay makes up about two-thirds of the United States’ gross domestic product (GDP). Since the entire labor force is around 160 million people, the 1.8 million people potentially protected under this deal constitute a bit more than 1 percent of the U.S. labor force. That means they’ll contribute roughly two-thirds of 1 percent of GDP — or around $133 billion to U.S. GDP. Even after paying for the proposed border wall, that’s still about a $100 billion net gain.

These are simplistic calculations providing only a rough estimate of the benefits of keeping so many individuals in the United States. But with a $100 billion margin, it is unlikely that more rigorous calculations would show a net loss to the United States from DACA.

Beyond the specifics of DACA and building a $30 billion wall, some pundits worry about the impact immigrants have on wages and employment for those already here. Luckily, ample economic theory and empirical evidence show those worries are misplaced.

Wages are ultimately determined by a worker’s productivity. Someone who produces more is more valuable to an employer. If someone is not well paid, he or she is likely to be poached by other employers who will offer more appropriate compensation for the relevant skills. Deporting immigrants (including Dreamers) will not boost a native worker’s productivity. This makes it unlikely that deportation will improve natives’ wages or employment prospects.

Concerns about falling wages and “stolen” jobs derive from a partial and misleading view of the economy, which considers only one aspect of what happens when people immigrate from one country to another. It is true that if we look at the immediate effect of immigrants entering the country — what economists call a partial-equilibrium analysis — a larger supply of workers lowers the wages of those already in the country. But, as the term “partial” suggests, this isn’t the full story.

First, if workers can be replaced either by technology or outsourcing at a fairly low cost, a change in the labor supply cannot have a large impact on wages. So, for instance, if we deport everyone who might be covered by DACA and reduce the labor force by 1 percent, the most wages can go up by will also be on the order of 1 percent. Someone earning a $10-per-hour wage might get a 10-cent-per-hour raise. It is nearly impossible to believe that such a massive dislocation of people can be justified by such a pittance.

Second, immigrants do more than compete with those already in the country for jobs. They also consume the goods and services that others produce, which means that immigrants also create additional jobs. If immigrants move into an area, they begin buying from the local grocery stores; because of the additional business, those stores can then expand and hire more employees in turn.

The only way that one can conclude from economic models that additional immigrants lower wages and employment opportunities is by using unrealistic assumptions, which treat the economy as if it were a fixed pie to be divvied out. In reality, the economy grows along with the population — and that’s true whether it grows from births or immigration.

The legal immigration process is in need of streamlining and expansion. But with the March deadline for a deal on DACA quickly approaching, that might have to come with a bit of a sour taste. Pro-immigration policymakers should consider making a trade to secure more open immigration policies and a deal for Dreamers, even if it comes at the cost of a wall.